The Platform Economy

09 November 2022Over the past decade, digital platform employment has been on the rise across the globe. These platforms connect different users, including companies, consumers, advertisers, and others. Since 2015, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) has been studying digital labour platforms to understand the future of work. A September 2022 ILO study found that platform workers in these new forms of employment face special challenges compared to traditional employment models, including their working conditions and social protections, and notes that international standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining apply to all workers regardless of status.

Many challenges for workers in the platform economy are common among regions. But in China, the scale of the platform economy, the conditions giving rise to the development of the sector, the profiles and calibre of the main corporate players, and the special regulatory environment all have unique features that affect workers. This explainer examines these angles primarily through the lens of two platform industries: the food delivery industry and the ride-hailing industry.

The companies operating in the platform economy offer new forms of employment that often fall outside of traditional legal frameworks - variously referred to as flexible employment and precarious employment - and they have also created a new labour model of the gig economy. China's major players today include the household names of Alibaba, Didi, Ele.me, Jingdong, Meituan, Taobao, and Tencent. Alibaba and Tencent are China's two internet giants. Online shopping platforms such as Taobao and Jingdong facilitate the exchange of goods between retailers and customers and then hire workers to complete the warehousing and delivery by couriers. Food delivery service platforms connect people with businesses serving meals, with Meituan and Ele.me sending the customer's order to the restaurant and the delivery rider then picking up the meal from the restaurant and delivering it to the customer. Ride-hailing platform Didi connects passengers with drivers in the system, who pick up passengers at their designated locations and take them where they wish to go.

China's platform economy is the largest in the world not only in raw numbers, but also in terms of proportion of the country's population. China's platform economy is growing rapidly, with platform workers increasing from 50 million in 2015 to 84 million in 2020, representing almost ten percent of China's employed population. Platform workers account for only about four percent of the employed population in the UK, and no more than one percent in the U.S. The ride-hailing and food delivery sectors have attracted workers at the highest rates. With a huge workforce and a wealth of capital, the platform economy has created enormous opportunities and challenges in China.

China's major corporate players did not require a lot of labour or material input in their early stages. Typically, the founders and a few programmers created the code and then started promoting their online services. For example, the China Pages listing site became Alibaba, and the founder of a social networking site went on to found Meituan. With capital investment, the companies created algorithms for the platform to match different users more effectively. As the platform accumulated data, it evolved from an information provider to a service provider and contracted with more workers.

These companies offered higher unit prices and subsidies to attract more workers. Initially, they offered wages that exceeded the average income of factory workers, flexible working hours, and more free time than on the assembly line. But as conditions have changed, with platform companies monopolising the market and algorithm development controlling the labour process, workers have little labour protections and have lost a degree of freedom. The labour and employment relationship between platforms and workers exists in a legal grey area, and legal redress is elusive. The periods allowed to complete an assigned task have grown shorter, while the income per task has also dropped, so overall income continues to decline.

Workers in the industry lack organisation and bargaining power yet still voice their grievances and make demands through collective action or individual protest. Despite government policies that have attempted to regulate platform companies since 2021, China's official union has failed to organise workers and initiate collective consultation in the industry, and platform workers continue to lack adequate representation. Workers who have sought to organise have faced repercussions, notably in the case of Chen Guojiang, an advocate for delivery workers' rights who was arrested in February 2021.

CLB recommends the official trade union take a greater role in protecting platform workers' rights and interests by creating platform industry sub-divisions within its official structure. The sub-divisions should allow for direct, individual union membership for workers, and worker participation in the union would establish a level of accountability. Union sub-divisions should engage in collective bargaining with platforms to determine fair piece-rate price standards based on different goods, routes, and road conditions, and to set limits on continuous working and driving time.

I. Scale of the Platform Economy and its Labour Pool

II. Labour Models of Platform Economy

III. Development of Platforms from Start-ups to Algorithm-Based Models

IV. Labour Conditions Under the Algorithm

V. Labour Disputes in the Platform Economy

VI. Platform Worker Resistance

VII. State Regulation and the Role of the Trade Union

I. Scale of the Platform Economy and its Labour Pool

The rise of China's platform economy is linked to economic changes in the country in recent decades, particularly the more recent decline in China's manufacturing sector. In the early 2000s, manufacturing in China's coastal areas grew rapidly, but with high worker turnover rates. In the electronics manufacturing industry, for example, companies tended to hire short-term workers due to fluctuations in demand for orders. When faced with changes in orders, companies would immediately resort to layoffs to reduce the excess labour force. Combined with the extremely high-pressure and demanding working conditions on the factory assembly line, more and more workers found the situation unbearable and eventually chose to leave.

Since 2010, China's manufacturing industry has increasingly mechanised to replace workers. Following the successful strike at the Honda auto parts factory in Foshan, Guangdong province, there was a period of increased worker protests and strikes across the country. The implementation of the Labour Contract Law (2008) and the Social Insurance Law (2010) further increased the cost of labour for companies, making it more desirable for them to introduce automation to replace workers. In 2013, China became the world's largest robotics market. A study by Torrent Network, a website publishing on social issues in China, shows that from September 2014 to January 2017, the number of factory workers in Dongguan, Guangzhou province, decreased by 190,000 as a result of "machine substitution." The installation of machines resulted in at least a 67 percent reduction in the workforce on production lines, and on some production lines, the reduction was as high as 85 percent.

These changes in the manufacturing industry provided a large labour reserve for the entrance of the platform economy, including food delivery and ride-hailing. Research and data in the food delivery industry provided by Meituan and Ele.me, as well as social science research, show that platform workers have entered the industry mainly from the manufacturing industry, with the next source being commercial service workers such from the catering industry, as well as those who were self-employed and worked for companies.

| Meituan data (2018) | Unemployed workers due to production cuts (31%) | Food and beverage industry staff (16%) | Self-employed/small business owner (13%) | Courier or delivery worker (12%) | Other delivery platform riders (8%) |

| Ele.me data (2020) | Workers (15%) | Office workers (14%) | Self-employed (12%) | Sales workers (8%) | Couriers (7%) |

| Zheng Guanghuai Research Team at Central China Normal University College of Social Sciences (2020) | Manufacturing industry workers (23%) | Agricultural, forestry and fishery workers (16%) | Commercial service workers (15%) | Construction workers (11%) |

Students (5%) |

Note: Surveys do not include the option "Other."

A similar situation can be seen in the platform economy in the transport industry, which emerged at roughly the same time as the food delivery industry. According to Didi's 2017 Platform Employment Research Report, the largest share of platform riders came from traditional manufacturing industries (e.g., textile, machinery manufacturing, chemical, concrete, aluminium), followed by traditional service industry workers (e.g., hospitality, retail, restaurant).

| Manufacturing | Service industry | Transport industry | Modern service industry (finance, intermediary, consulting, e-commerce, etc.) | Health, education, public administration | |

| Didi data (2017) | 26% | 18% | 17% | 11% | 6% |

From 2010 to the present, platform companies have continued to recruit high volumes of workers. Since 2020, the worker population of platform businesses grew even more rapidly as more semi-unemployed workers flocked to platforms to maintain basic income in the midst of the pandemic. The number of riders taking orders on Meituan's platform reached 2.95 million in the first half of 2020, an increase of 415,000 or 16.4 percent year on year, compared to the first half of 2019.

Company data on the number of workers in the food delivery industry is difficult to parse, as registered workers far exceed the number of workers actively taking orders in any given period. For example, according to reports, 7 million riders were registered in the food delivery industry in 2019, but the number of active riders in 2021 was likely closer to 2.14 million according to available data. At the same time, the number of people in relatively permanent employment on the platform is increasing, which means that more and more workers are using the platform as their primary means of livelihood.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Meituan | 14,000 | 172,000 | 531,000 | 600,000 | N/A | Over 1 million |

| Ele.me | N/A | N/A | N/A | 667,000 | 850,000 | 1.14 million |

Finally, according to the ILO, as many as 90 percent of workers in the major platform economy industries of food delivery and ride-hailing are male. Workers also tend to skew younger than in other industries. Migrant workers make up over half the workers in the food delivery industry, whereas ride-hailing drivers are more likely to work in the place of their residency.

II. Labour Models of Platform Economy

The platform economy encompasses a wide range of jobs, including live streamers, domestic workers and caregivers, designers and programmers, and others. Each industry within the platform economy has its own labour challenges. In this explainer, we focus on the food delivery industry and the ride-hailing industry because they are the fastest growing platforms with a large labour force. Other large and growing industries, such as the express delivery industry, do not crowdsource workers in the same way or adopt their own e-commerce platforms, making this type of labour very similar to traditional logistics work.

Food Delivery Industry

Before the development of delivery platforms, restaurants often directly hired employees to deliver to customers. Starting in 2008, platforms such as Ele.me, Point Me, Meituan and Baidu Takeaway - which was purchased by Ele.me in 2017 and is now called Ele.me Star Elite - emerged one after another and began providing uniform delivery services for restaurants. Restaurants had previously hired their own delivery workers, but as more customers used the platforms to order food, businesses also signed on to hold onto their business. As the platforms gained market share over both businesses and customers, the model has created coercive conditions for businesses trapped in the system as well.

In the early days, delivery platforms offered generous terms to workers to compete for market share. These included overtime pay, compensation for illegal dismissal, and other economic compensation. Occasionally, food delivery platforms employed temporary workers. This was often done through labour dispatching, meaning hiring workers through an employment agency. However, with the 2014 implementation of the Interim Regulations on Labour Dispatch and other laws and regulations thereafter, the widespread use of labour dispatch has been restricted.

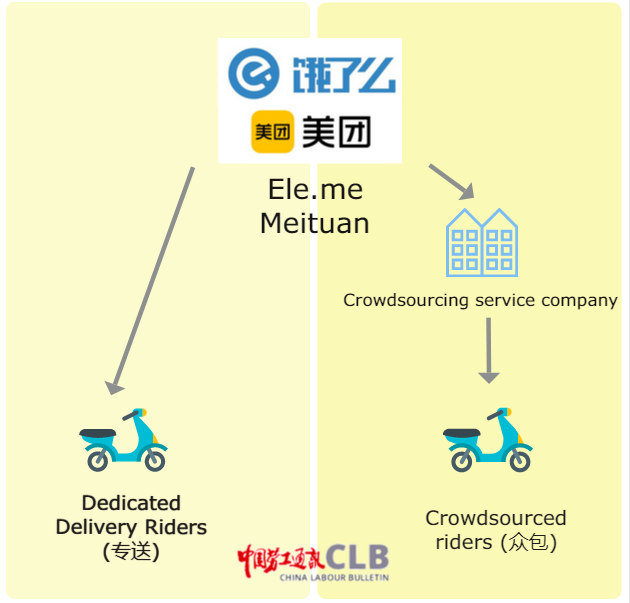

As competition among delivery platforms heated up there was a fundamental shift in the employment model used by delivery platforms. Gradually, the labour costs and employment risks were shifted to crowdsourcing service companies and distribution providers under the slogan of "freedom in taking orders and working part-time on multiple platforms," which attracted more riders. Initially, the platforms still recruited crowdsourced riders directly, signing cooperation agreements with them and purchasing accident insurance on their behalf. Later, platforms began to cooperate with crowdsourcing service companies that signed agreements with the crowdsourced riders, paid them, and purchased insurance, complicating the labour relationship between the rider and the platform (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The two early employment models used by food delivery platforms

As delivery platforms have begun to outsource the delivery business, this use of joint delivery vendors completely wipes away the legal relationship the platforms used to form with dedicated delivery riders.

To illustrate, on March 25, 2022, Workers Daily reported on a workplace injury case involving a delivery worker, in which the rider's employment relationship involved five separate companies in four cities. In 2019, the worker, Shao Xinyin, sustained injuries including broken bones while delivering food for Ele.me in Beijing. In pursuit of his rights, Shao travelled from Beijing to Chongqing to assert his rights in court:

I was sent out for delivery by the Ele.me platform, and I worked at the food delivery station for DYS Logistics (Chongqing) Co., Ltd., located in Beijing's Changping District, but my salary was paid by Taichang (Chongqing) Food and Beverage Management, and taxes were withheld by a construction company in Tianjin and an outsourcing company in Shanghai.

Ele.me, DYS Logistics, and Taichang all denied any employment relationship with Shao, making his path to defend his basic rights through legal channels extremely difficult. First, he applied for arbitration in Changping district, Beijing, to confirm the labour relationship with DYS Logistics, and he won. Then, he brought the case against DYS Logistics in its place of registration in Chongqing to certify the application for work-related injury. Unfortunately, this claim was not successful, and Shao has not received his workplace injury insurance benefits.

There are two major categories of delivery riders: dedicated delivery riders and crowdsourced delivery riders. The proportion of workers falling in each category is roughly half.

Under the dedicated delivery model, all riders work full-time and belong to a "platform - delivery vendor - delivery station" model. More than half of the delivery hubs sign labour contracts with dedicated delivery riders, stipulating the riders' wage structure and payment methods, including the unit price of piece-rate pay and monthly unit volume requirements. However, these labour contracts do not fully comply with labour laws, as most of the platforms do not pay the required social insurances. At the same time, riders are subject to strict offline management and need to reach the delivery station's monthly assessment indicators. Every morning when the workers come to work, the station manager announces the previous day's single volume and customer evaluations, and pushes the workers to reach targets and practice good customer service.

Crowdsourced delivery riders are engaged in a form of flexible employment, and platforms will not place strict demands on the number of orders and work time that workers put in. But this does not mean that workers are not restricted by platform algorithms. Platforms link delivery volumes with the unit price, which on the one hand encourages riders to complete more delivery orders, and on the other hand secretly penalises those riders who deliver fewer orders. Platforms raise the intensity of labour for crowdsourced delivery riders by strictly regulating delivery times, and also use customer reviews to ostensibly raise workers' service quality. In recent years, delivery platforms have also tried to strengthen labour management under the crowdsourced delivery model. Services like Meituan's "Lepao Rider" (乐跑骑手) and Hummingbird's "Preferred Rider" (优选骑手) clearly stipulate the daily order volumes and times crowdsourced riders must fulfil.

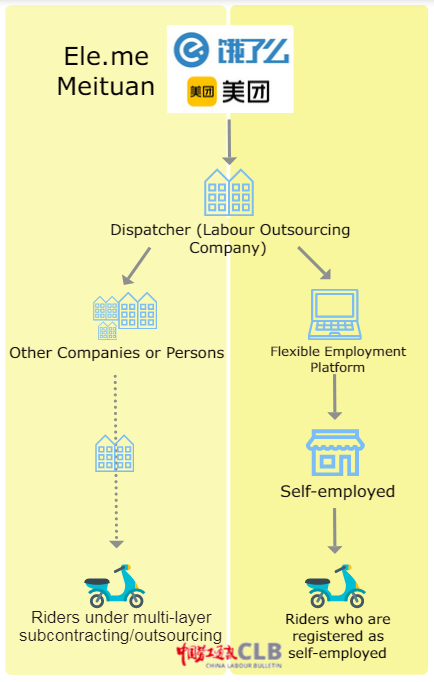

Aside from dedicated delivery riders and crowdsourced delivery riders, delivery service providers can also cooperate with flexible employment platforms, changing dedicated delivery riders into self-employed workers. Recent surveys have shown that some delivery service providers have avoided the Labour Law by demanding that dedicated delivery riders register through flexible employment apps as self-employed workers and then sign employment contracts with the flexible employment platform.

As employment models have evolved, food delivery platforms and delivery service providers have completely avoided employment risks and have transferred risk to the individual riders. Under current legal frameworks, self-employed workers are those who take on their own risk, including bearing businesses losses, and they cannot expect the flexible employment platform to provide the protections and benefits stipulated by the Labour Law. Riders who are registered as self-employed workers will not have a labour relationship under the law with a company, and their work times are not subject to any restrictions. Nor will companies make payments for social security, such as pension and work injury insurance, and they can terminate employment at any time without paying any compensation. At present, there are more than 1.6 million riders considered self-employed in China.

Figure 2: The increasingly complex relationships between platforms, riders, and intermediaries

Zhicheng Migrant Workers Legal Aid and Research Center in Beijing compiled a database in September 2021 of 1,907 court cases. These cases involve food delivery riders, and the judges rule on labour relationships. This database has been used to map the evolution of food delivery platform employment models.

Zhicheng's report produced from the database found that in cases of workplace injury, the rate of a court finding of a formal employment relationship between the platform and the worker has remained around one percent. When workers' rights are violated, the employment responsibilities that were originally taken on by food delivery platforms were nearly all transferred downstream to logistics providers and crowdsourced delivery service companies.

Even as employment patterns have continued to develop, and labour relationships have become more fragmented, more and more food delivery workers have moved from temporary work to permanent work. Ele.me's "2022 Blue Rider Development and Assurance Report" shows that more than 40 percent of riders are working full-time, and among the remaining 60 percent of riders who have income from other sources, about 40 percent have other types of jobs and 30 percent are engaged in delivery for other platforms.

Therefore, delivery work is already the chief source of income for about 58 percent of food delivery riders, and the trend in employment among delivery riders is shifting toward full-time work. Still, they do not have many of the labour protections of full-time workers. Although they do not have employment relationships with food delivery platforms, they are controlled by the commands of these platforms rather than dictating their own working terms. Food delivery platforms do not need to involve themselves in the daily management of food delivery workers, but can firmly control the labour of riders through platform algorithms.

Ride-Hailing Industry

As with the food delivery industry, the transport industry uses both full-time and part-time workers, but with a higher percentage of full-time employees. According to a 2021 Tsinghua University report on the transport industry in China's major cities, full-time drivers account for over three-quarters of the ride-share market. The transport industry includes ride-hailing platforms such as Didi Chuxing, which is basically a monopoly. In the early 2010s, Alibaba invested in Kuaidi Dache and Tencent invested in Didi Dache, and in 2015 these companies were merged into Didi Chuxing, which recently bought Uber's China operations.

Photograph: abolukbas / Shutterstock.com

A survey of hundreds of app-based drivers in Guangzhou found that most of Didi's affiliated companies signed labour contracts with full-time drivers, and that as many as three-quarters of part-time drivers had labour contracts, and more than ten percent had signed service agreements. However, only about 60 percent of drivers had pensions, and just 55 percent had unemployment insurance. This lack of proper insurance is a violation of the Labour Law and is not unlike the situation for workers in the delivery industry.

The survey also showed that while most drivers had medical insurance, this coverage had often been purchased by the drivers themselves locally and had not been provided by platforms. Nor do companies provide other employment benefits, such as paid maternity leave, medical leave, annual leave, housing funds and so on. As for work-related injury insurance, which is closely related to the safety of drivers at work, less than half of drivers were provided coverage. This data includes both full-time and part-time drivers, but it can be inferred that part-time drivers as a group experience the lowest rates of employment benefits.

Compared with riders for food delivery platforms, drivers for ride-hailing platforms move more quickly from part-time to full-time employment. Some drivers initially joined the industry on a part-time basis and have gradually become full-time. Platform drivers point out that because platforms claim high commissions, and other costs such as fuel, electricity and vehicle rental are high, many part-time drivers have little choice but to become full-time in order to subsidise their expenses. In recent years, the repercussions of the pandemic and economic instability, and large numbers of workers losing their former jobs, has intensified the phenomenon of workers supplementing their income with ride-hailing jobs, increasing the overall number of workers working through the platforms on a regular basis.

III. Development of Platforms from Start-ups to Algorithm-Based Models

The rise of platform companies has developed China's domestic economy, linking producers and consumers and absorbing tens of millions of workers. However, these companies have been able to control the labour force virtually unchecked by developing algorithms and avoiding the signing of labour contracts with workers, skirting labour laws at the expense of workers' rights. The scale and rapidity of this growth and the level of integration with daily life for China's citizens have all contributed to the unchecked assault on the rights of the workforce.

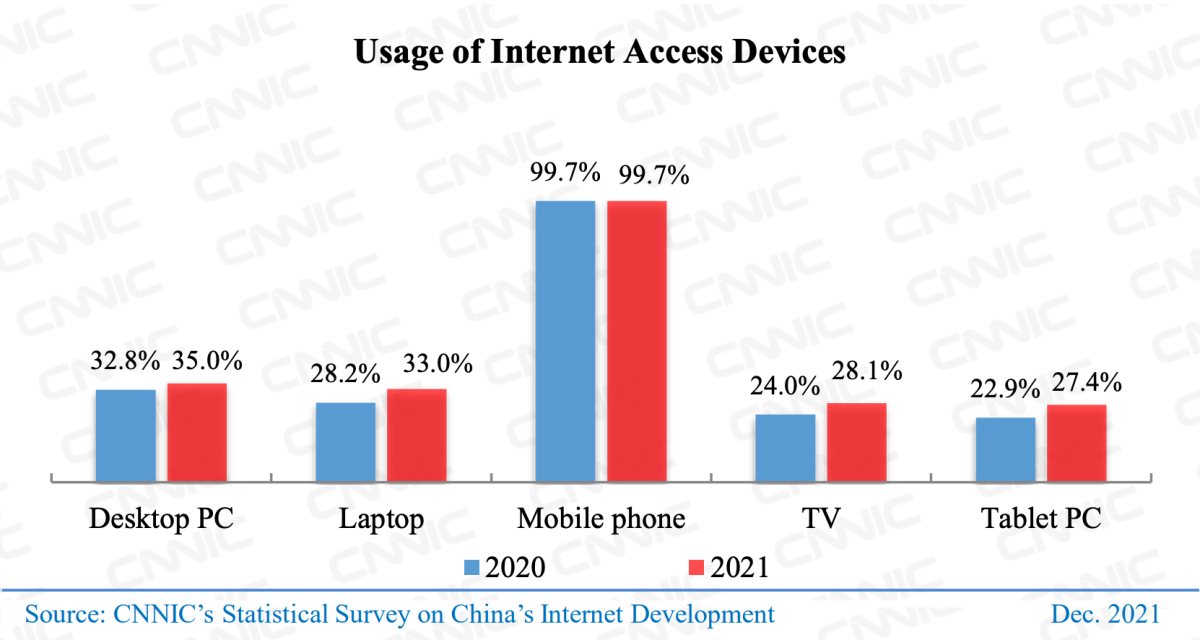

Mobile Internet Environment Gives Rise to Online Platforms (2008 - 2013)

Starting in 2008, 3G mobile communication technology was universally available in China, and mobile phone production and use quickly soared. Unlike in other regions where desktop computers were people's first portal to the Internet, mobile internet users in China surpassed 70 percent of the population in 2013 and reached 83 percent in 2020, while the rate of broadband internet access reached 73 percent in 2021. At the same time, the rise of e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba popularised the infrastructure for online payments, allowing the general population to quickly become accustomed to shopping and making payments using their mobile phones. These were essential conditions for the growth of platform companies in China, which rely on a broad customer base and changing user habits.

From the end of 2013 onwards, capital flowed into China's food delivery market. At the end of November that year, after operating for several years in the delivery business, El.me received $25 million in Series C funding led by the venture capital fund Sequoia Capital. The same month, Meituan, which previously focused on group buying, launched its delivery service. In December, Alibaba's Tao Diandian was launched. In May 2014, Baidu Takeaway entered the market. The apps developed by these and other platforms gradually became popular.

A similar influx of capital occurred at the same time in the ride-hailing industry. In 2013, Alibaba invested in Kuaidi Dache and Tencent invested in Didi Dache (now Didi Chuxing), while another platform, Yongche, received financing from other investors. What followed was a period of rapid expansion for the ride-hailing industry, with an ever-increasing number of cities covered by the business model.

Price Wars to Gain Market Share (2014 - 2016)

Platform companies launched price wars in 2014, fighting to expand their consumer base and compete for market share. In September of that year, Meituan and Ele.me engaged in a subsidy war to win the market of university students on campuses, and later for white-collar consumers. At the height of this fierce competition, there were even cases of recruitment employees and riders for competing platforms getting into fistfights.

To successfully capture these markets, the companies recruited a huge labour force through offline promotion. Then, mobile payment services facilitated subsidies and incentives to attract customers and workers alike to sign up for the platforms. Subsidies rose from five yuan per order to as high as 20 yuan per order. According to estimates at the time, Didi was paying as much as 100 million yuan per month in subsidies.

The subsidy war continued intermittently for a year or two, resulting in monopoly-like conditions in both the food delivery industry, dominated by Meituan and Ele.me, and in the ride-hailing industry with Didi. The price wars not only opened up the consumer market for platform companies, but also resulted in the losing companies being swallowed up by acquisitions, so that the scale of winning companies kept growing and growing.

As fierce competition morphed into monopolies, the treatment of workers changed sharply. The companies were no longer courting a workforce with incentives to join, and the work conditions and pay rates deteriorated. For example, a delivery rider interviewed in 2016 by The Beijing News said that when he joined Baidu Takeaway in 2015, he handled around 500 orders a month and his working hours were fixed, starting at 10:00 am and finishing at 6:00 pm. The eight-hour work system made him feel that he could handle things with ease. The monthly income of more than 4,000 yuan was satisfactory to many delivery riders.

However, by the end of that same year, the rider found that his monthly orders had increased to 750, and the order-taking system changed from one in which workers could choose orders to one that assigned orders, preventing workers from taking breaks. By 2016, the working hours of delivery riders were significantly longer, and the eight-hour shift was gone: "From 11:30 am to 2:30 pm you must be on duty, and from 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm you've got to be on the road." Despite taking more orders and working longer hours, the monthly incomes of riders saw no significant increase because the unit price for deliveries had gone down, and platforms also began implementing strict policies for rewards and penalties. These management systems are based on algorithms to maximise profit without regard for human conditions.

Algorithms Control Labour (2016 - present)

When consumers swarmed to the platforms and the competition between platform companies was most intense, companies had to fulfil the huge number of orders by recruiting more workers. But soon, the platforms also innovated their technology so that the same worker could fulfil more orders than ever before in the same amount of time, also resulting in more profit to the company.

To increase the labour intensity of workers, delivery platforms invested a lot of capital in developing algorithms to handle the labour involved in delivery planning. This includes workforce assignment, supply and demand matching, and route planning. The use of computing meant that algorithms could replace human labour, analysing the mass of data accumulated by the company to carry out classification, allocation and even prediction at much faster speeds.

One example is how Meituan designed and improved algorithms to more accurately mark the locations of orders, which could then be redefined to allow riders to travel shorter distances between orders and reduce the empty bag rate of driving to new locations without order on board. In one of Meituan's trials, the average rider cut more than 100 metres of driving distance per order, and the average driving distance dropped by 5 percent. With the huge scale of orders on the platform, the distance saved by riders is considerable, increasing the number of orders that workers can deliver.

Photograph: janusz.kol / Shutterstock.com

Sociologist Chen Long of Peking University conducted research that shows how algorithms guide riders through the process of taking and delivering orders. The algorithms reduce the amount of time workers spend waiting, planning, and delivering orders, and subsequently reducing labour time per order. In the "order to store" feature in the system, riders can see heat maps that identify areas where orders are dense, so they can focus on areas of high demand to await and take orders. In the "arrival pickup" section of the system, riders can check estimated delivery times for orders. When there are multiple orders to be picked up, the rider can plan the order of pickup according to the estimated delivery time of different orders. The "pickup delivery" function then allows riders to deliver meals according to delivery routes planned by the platform system, which improves the accuracy and timeliness of delivery. The time saved by these algorithms results in shorter average delivery times for riders and higher delivery volumes, creating more value for the platform.

It is worth noting that the labour of workers is becoming simplified as algorithms replace more of the planning and decision-making during delivery. The factory-style monotonous labour that many delivery workers hoped to escape is now being reintroduced to them in a different industry. A clear example is Meituan, which has designed an algorithm to determine when riders should contact customers, eliminating the need for workers to make decisions during delivery about when to call customers about their order.

The company has also developed wearable technology to manage communication with customers. In the past, riders had to take out their phones to contact customers during delivery, which was not only a complicated step but also dangerous while driving. A voice assistant developed by the platform now calculates and judges the timing of calls, automatically dialling after confirmation by the rider. This algorithm is now being integrated into a trial version of smart helmet, and - with a built-in Bluetooth module - riders can simply click on a shortcut button on the left side of the helmet to answer incoming calls. The system will automatically answer calls if no action is taken. The app will also give riders instructions from their helmets to take orders, grab orders, transfer orders, and so on. Riders can simply click on the shortcut keys to complete the confirmation or verbally reply with "confirm" for operation. This not only saves labour time for workers, but also transforms the work of the rider into basic delivery work.

According to an article by the technical team at Meituan, from 2015 to 2018 the AI development team managed to reduce the length of delivery times by one-half, from one hour to 30 minutes. This coincides with the trend revealed in the People magazine article, "Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System." The article opened with an interview with a station manager for Meituan who reported that "between 2016 and 2019, he had received three separate notifications on the Meituan platform for acceleration [of work]. In 2016, the time limit for a three-kilometre delivery was set at one hour; in 2017, it became 45 minutes; and in 2018, it was shortened by another seven minutes, settling at 38 minutes."

In the ride-hailing industry, algorithms have played a similar role. The most basic function of algorithms in ride-hailing apps is the real-time matching of vehicles with capacity to passenger demand. With the continued development of algorithms, the precision of matching has continually increased, lowering the vacancy rate for drivers. One research study showed that vacancy rates in ride-hailing were significantly lower than those of cruising cab drivers. This was particularly the case in Shenzhen, where the vacancy rates of taxis were highest and the rates for Didi were the lowest, at just half that of taxis. In Beijing, vacancy rates for Didi are also lower than those for taxis. By increasing the time drivers spend with passengers, the platforms are able to increase their commissions and generate greater profits for themselves.

Through a "globally optimal mode," algorithms reduce the total time it takes for drivers to pick up passengers. The algorithm considers more than just the closest vehicle to a particular passenger in linking drivers and passengers. If the closest vehicle to a passenger is the only consideration, another passenger may be forced to wait for order acceptance from a vehicle that is further away. Therefore, the algorithm considers the distance between available vehicles within a given range in reference to all passengers in order to find the solution that takes the least amount of pickup time for both drivers and passengers. According to Didi engineers, this vehicle allocation model saves drivers and passengers on the platform a total of 300,000 hours of travel time each day. In fact, it will at the same time help the platform reduce the inefficient use of time to generate more profit.

Finally, the data and algorithms accumulated by the platform companies is increasingly overlapping. As workers' labour processes are recorded by the platform, this newly collected data can then become the raw material for algorithms. This data stream allows companies to have a more accurate analysis and a better picture of the labour process and thus design new ways to compress workers' labour time. The previous mention of Meituan's more accurate labelling of consumers' next location is the result of such a process. Meituan updates the consumer's location with data from the rider's post-delivery check-in and is able to obtain more accurate information than the address filled in by the user. As riders continue to expand the range of food delivery services, the platform will become richer in information about the positioning of consumers.

IV. Labour Conditions Under the Algorithm

The algorithms developed by companies reduce workers' time per order, allowing them to pick up more orders, but this also has given platforms a justification for driving down workers' wages. For individual workers, filling more orders in the same amount of time should mean an increase in income. From the standpoint of capital, however, when labour times accelerate for workers, this means that the amount of labour required to complete each order goes down, and platforms can therefore lower the unit price paid to workers.

According to Meituan's 2018 prospectus, the compression of logistics time has led to a one-third reduction in labour cost expenditure per order. Meituan commissioned a report from iResearch Consulting Group that found that the labour cost per delivery in China has declined at a compound annual growth rate of 7 percent, from 10.3 yuan to 7.6 yuan since 2013. The report concludes:

Historical decline in labor cost per food delivery transaction is primarily driven by significant increase in the number of transactions per delivery rider and improvement in logistical systems. Businesses are also adding additional delivery services in non-peak period for food delivery in an effort to lower unit labor cost per transaction by allocating fixed costs throughout the day. Going forward, labor cost per delivery transaction is expected to remain at approximately RMB7, according to the iResearch Report.

In the early days of the delivery industry expansion, the monthly income of full-time delivery workers was higher than that for other industry jobs, drawing many workers to the industry. They were told that delivery workers could easily earn tens of thousands of yuan every month. The Beijing Business Today reported in 2016 that Meituan delivery workers in Beijing earned a monthly base salary, and that commissions were calculated on the basis of order volume, so that higher numbers of orders translated into more commissions. Those riders working longer hours could earn as much as 7,000 to 8,000 yuan a month, higher than the wages of real estate agents, sales representatives, and many other jobs.

However, even at that time, many platform workers had already seen a declining trend in wages. An article in Beijing Youth Daily showed that the average wage of food delivery workers was about 4,000 yuan, about half the amount touted to lure in riders. One delivery worker interviewed for the article said that his delivery station was no longer recruiting, and that the 300-500 yuan newcomer referral fee incentive originally offered by the company to introduce new riders had been eliminated.

Once the price war died down, prices continued to drop. Chen Guojiang, the food delivery worker who set up chat groups and spoke out against labour violations in the industry before his February 2021 arrest, was interviewed about this topic, based on his experience working as a food delivery rider since 2009. In an online discussion symposium transcribed by the WeChat account Tying Knots, Chen described how he has witnessed rapid changes in the industry. He said that the unit price drop is not only due to recent crowdsourcing in the industry:

This is not just the case for crowdsourced delivery and dedicated delivery, but everything is like this, even for direct employees. The official riders got 10 yuan per order before, or even 11 or 12 yuan, but these gradually fell to 9, 8, 7 yuan… and in smaller cities it was even lower.

As the unit price per order has decreased, riders must fill more orders to maintain their original salary levels. However, the influx of an increased workforce is making this even more difficult to achieve because of competition for orders. As a result, workers are working longer hours, and some workers who were only sporadically taking orders are becoming more like full-time workers. A survey conducted by Beijing Yilian Legal Aid and Research Center of Labor shows that in Beijing, riders generally work more than 10 hours per day.

The hours are long and the work is intense. Yet due to physical limitations, many are just barely making up for the decline in unit prices. Data released by Meituan in 2018 showed that just 42 percent of dedicated delivery riders made salaries in the 4,000 to 6,000 range, while 39 percent brought in 2,000 to 4,000 per month. Wages were even lower among crowdsourced delivery riders, of whom 39 percent made below 2,000 yuan. Only 31 percent of crowdsourced riders made between 2,000 and 4,000 yuan per month. Overall, workers' wages are not higher than in the past.

The same relative decline in wages has occurred in the ride-hailing industry, though in a slightly different way than in the delivery industry. Transportation platforms make profits by taking a commission from the driver's share of a single trip, and in order to get more money to expand their markets and services, the platform's service fee has not been reduced over the years. The aforementioned 2021 Tsinghua University report on the transport industry in China's major cities shows that most drivers believe that platform commissions are too high, and when fuel costs, electricity, vehicle rental, and other costs are combined, the cost of operating a ride-hailing car is too high. To adapt to the rules of the platform and offset the daily costs, many part-time riders choose to go full-time.

According to the Tsinghua report, the average rider works 11.05 hours a day and 6.45 days a week. Half of the drivers reported working 8-12 hours a day, while 27 percent work 12-16 hours a day. For drivers working part-time, only 16 percent work four to eight hours a day, and just three percent of drivers work less than four hours a day. In terms of weekly travel time, three-quarters of ride-share drivers work seven days a week, and the proportion of drivers working less than five days a week is less than 10 percent. This shows that the vast majority of drivers are becoming full time and are working long hours, more hours even than delivery riders.

By significantly extending working hours, drivers can maintain higher wages than in other industries. After deducting various types of rent, fuel costs, and the platform's commission, the actual monthly income of the drivers surveyed averaged at 7,711.29 yuan. Just over half of ride-share drivers earn between 6,000 and 10,000 yuan per month, and one-quarter earn 3,000 to 6,000 yuan per month. About seven percent earn less than 3,000 yuan. The number of drivers earning more than 10,000 yuan is only about 10 percent. The survey points out that very few drivers can earn high incomes of over 10,000 yuan, and these drivers are generally out working in their cars 12 to 16 hours per day. It may even be necessary for teams of drivers, often a husband and wife, to drive together in shifts for the work to be sustainable. Of course, there is a physical and mental cost of earning this income.

V. Labour Disputes in the Platform Economy

As platform workers become a larger proportion of China's workforce, related labour and employment disputes have also increased. In the delivery industry, workers are frequently involved in traffic accidents, leading to legal questions over liability and insurance coverage, medical expenses, and other compensation. The penalties set by the platforms for late deliveries and poor customer reviews encourage workers to ignore traffic safety rules and risk their own lives as well as the lives of other drivers and pedestrians to complete the platform delivery requirements and avoid fines. It is not uncommon for delivery workers to run red lights, go against traffic flow, and to weave in and out between larger vehicles. Statistics from the Shanghai Public Security Bureau show that as of September 2020, more than 43,000 traffic violations of all kinds involved couriers and food delivery riders. In 2020, there were 423 road accidents involving the express delivery industry in Shanghai, resulting in 7 deaths and 347 injuries, with an average of about one injury per day.

Many of the incidents are quite serious, and workers and their families have difficulty holding companies responsible. In 2020, a 43-year-old delivery worker surnamed Han from Beijing died of exhaustion on his way to deliver a food order. Although he had purchased accident insurance through the Ele.me platform, the company asserted that he had not been directly employed. As a concession, Ele.me offered to pay the Han family only 2,000 yuan in compensation. Less than two weeks later, in the city of Taizhou, Jiangsu province, a 47-year-old delivery rider surnamed Liu set himself on fire in front of Ele.me's local office due to non-payment of his wages. And in August 2022, another food delivery worker in Taizhou stabbed himself in front of his delivery substation, also in protest over fines and unpaid wages.

In these and other cases, workers are not able to turn to legal mechanisms ordinarily available for such labour disputes. This is because platforms do not legally recognise delivery workers and ride-share drivers as employees, characterising them instead as self-employed individuals contracting for services. Therefore, the traditional forms of legal recourse are not available or effective in labour disputes involving platform workers. When workers try to seek help through labour dispute arbitration or civil litigation, they often cannot even meet the first step of dispute resolution: establishing a formal labour relationship.

Platforms Require Workers to Click Away their Labour Rights

Workers enrolling in platform labour accept electronic agreements stating that the "delivery provider" (the worker) is not in a labour relationship with the company. Such agreements essentially force workers to sign away their labour rights. These clickthrough agreements have been upheld in court.

For example, a district and a municipal court in Jiangsu province both upheld such an agreement in the case of a Meituan food delivery worker surnamed Cai, who died while on the job. Cai was a crowdsourced delivery rider who signed an electronic agreement that contained multiple consent forms for the various terms and conditions.

The registration agreement for Meituan crowdsourced riders states, "Once you have filled in the information as prompted on the registration page, and have read and consented to this Agreement and completed all registration procedures, this indicates that you have fully read, understood and accepted all of the contents of this Agreement and have reached an agreement with the company to become a labourer for the company." There is also a check box indicating, "I have read and agreed to the Crowdsourcing Platform Service Agreement, the Labour Agreement, and the Wallet User Payment Service Agreement."

Because of these contract clauses, the Jiangsu courts denied the existence of a formal labour relationship with Cai and ruled that what had been contracted between the company and the deceased rider was instead "labour relations." Legally, this means that Meituan and any intermediaries are not liable to pay workplace injury or death compensation, as those provisions only apply to formal labour relationships.

According to laws and regulations (see our explainer on Workers' Rights and Labour Relations in China), a formal labour relationship is established through a written labour contract signed by the employer and employee containing information about the specific nature of the work, necessary qualifications, and so on. Under the platform economy model, however, contracting for labour is a very one-sided process in which workers and the company are not on even footing. Specifically, there is an information gap balanced in favour of the platform and against workers, and it is not always clear to the worker what rights and interests they are giving up when registering to work.

Workers download the platform app, register personal accounts with only basic information, complete an identity verification process, and then check a few boxes indicating they have read and agreed to a long list of terms and conditions. The application is automatically registered as complete, with no human entity from the platform's side involved. In this way, workers have no choice but to "agree" in a single click if they want to work for the platform, and of course almost no one carefully reads the terms and conditions or attempts to lodge an objection.

The Fragmentation of the Labour Relationship

In the absence of a labour contract, the law recognises other ways to establish a formal labour relationship. A 2005 notice from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security gives guidance on identifying labour relationships. This notice provides that evidence of payment of wages, social security benefits, work certificates, work attendance records, or other documentation can support the legal finding of the establishment of a formal labour relationship. This notice is meant to balance power dynamics in the workplace, where it is the employer's responsibility to sign labour contracts according to law, yet lack of such a contract makes it impossible for workers to assert their subsequent rights against the employer. In effect, the notice recognises de facto labour relationships where a contract is absent.

However, even when delivery riders provide wage payment vouchers or work attendance records, platform companies can still manage to dodge labour relationships with riders. By stating to the court that the platforms only provide information services to workers, do not physically supervise their riders, and do not directly pay their wages, platform companies have been successful in convincing courts that they are not the workers' employer. An article by the youth news account Masses investigated judicial decisions and found that in labour relationship disputes between riders and Beijing Sankuai Online Technology, the parent company of Meituan, the court consistently ruled that the company had no direct labour relationships with workers.

Even though it is nearly impossible to establish a labour relationship with the platform companies themselves, some workers have had success in their labour disputes with intermediaries. The aforementioned article from Masses showed that court rulings had found that intermediary agencies had hired workers as service providers according to the legal criteria emphasised in traditional labour relationships. In certain situations, the court has also ruled that there was a contracting relationship or a full labour relationship with workers.

In a 2019 case in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the court pointed out that the delivery worker, surnamed Li, had been under the management of an agency, Jieshun Delivery. This finding was based on evidence of dress code being enforced, payment of wages, and the scope of services performed. Based on this, the court ruled that there was a labour relationship between the agency and the worker.

However, the delivery industry is increasingly fragmented, complicating the question of labour relationships. In the case of the injury of the delivery rider surnamed Shao mentioned above, five different entities were identified in his pursuit of workplace injury compensation. In addition to the platform company, one company gave him his work orders, another paid his insurance, another his wages, and another his taxes. Shao was engaged in delivery full-time and used only the Meituan delivery app. Every day, Shao would clock in and out of work according to the hours specified by the local delivery hub, and he could not refuse the orders arranged by the system regardless of high-traffic periods and inclement weather. Generally, small rest periods and vacation time required the approval of the local hub. Nevertheless, Shao was unable to hold the hub legally responsible, and his claims against the other entities identified also were unsuccessful. After two years and five separate judicial proceedings, no labour relationship was found.

VI. Platform Worker Resistance

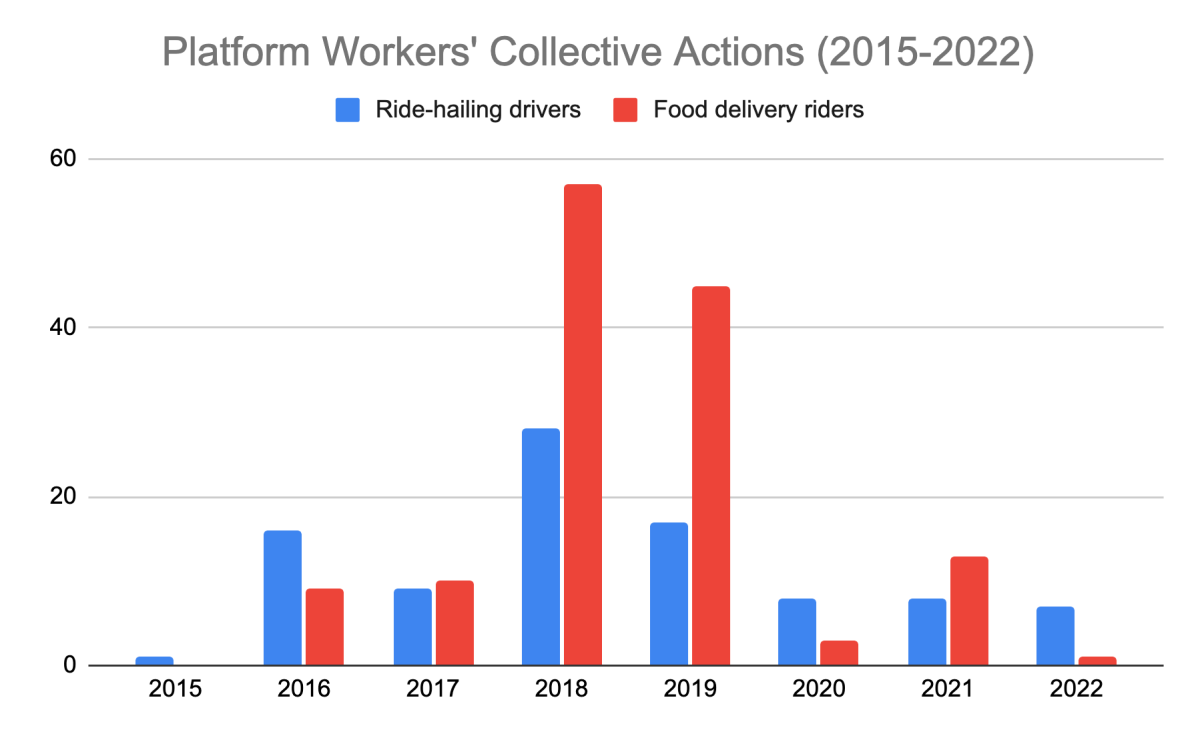

Facing continued declines in unit prices and platforms evading responsibility for the rights of workers under the Labour Law, platform workers have resorted to collective action to protect their rights. In 2015, protests by ride-share drivers were recorded for the first time in the CLB Strike Map, and in 2016 the first cases involving food delivery riders appeared. Since that time, collective actions by platform workers have steadily increased.

As seen from the CLB Strike Map, the variety of demands from platform workers has increased over time. In the beginning, their opposition was mostly to seek unpaid wages and to demand pay increases. But today, they also push back on issues such as overtime, lack of management oversight, and poor working conditions. ride-hailing drivers, meanwhile, typically rent the vehicles from the platform company. Lately, one of their demands is to return their vehicles and get out of their rental contracts, because business has fallen during the pandemic. Drivers have also expressed dissatisfaction with management methods.

Photograph: Chintung Lee / Shutterstock.com

Protests by ride-hailing drivers at the beginning were concentrated around the issue of diminishing company subsidies and incentives. In 2017, there were three strikes by drivers from Didi, and the protest demands all centred on diminishing company subsidies and incentives. For example, drivers protested over flat-rate fares and high temperature allowances. From 2018 onward, ride-hailing platforms raised their commissions on drivers, resulting in the outbreak of over 20 drivers' strikes in Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hunan, and Jiangxi provinces, among other areas.

By 2018, Didi drivers staged continued strikes between February and August to protest increases in platform commissions and drops in the base price. That year, protests by drivers demanding increases in income reached a peak. Once the pandemic hit, protests over high commissions fell significantly, and demands focused instead on issues of driver saturation in the industry and cost issues. In particular, drivers protested against new driver recruitment policies on the platform and against high vehicle rental fees through the platform company. Moreover, workers demanded that they be able to return their leased vehicles, creating conflict with companies.

For food delivery riders, the main demand has shifted from unpaid wages to salary increases and then to benefits. In 2016, the vast majority of workers protested against unpaid wages, and there were only two incidents recorded of workers protesting the company's withholding of subsidies. By 2017, however, protests for wage increases were rising, and grievances against the platform for increased fines and deductions from subsidies began to emerge. For example, in August 2017, drivers for Meituan in Xuzhou, Jiangsu province, went on strike to protest against lower delivery fees and shorter delivery times. In September 2017, a Baidu delivery registered company in Shanghai's Jiading district failed to pay wages and surge fees. The boss ran away, leading to a collective protest by workers.

Protests by delivery workers reached a peak in 2018. Meituan delivery riders from more than a dozen cities, including Chongqing, Hefei, Shanghai, Yantai and Linyi, launched collective protest actions between May and June.

Notably, food delivery workers have organised mutual aid and collective actions through self-organisation among workers. Beijing-based delivery rider Chen Guojiang, for example, set up WeChat groups to unite delivery riders in 2019. According to Chen, he set up sixteen different groups reaching over 14,000 food delivery riders.

Seeing that riders had no bargaining power and platforms could do whatever they wanted, the goal of the WeChat groups was to become a platform for riders to assist each other. Chen recorded numerous interviews and videos documenting the daily labour situation of delivery workers, exposing the suppression of workers by platforms. He criticised the platforms' blatant violation of labour laws, fining workers for late delivery, and other improper actions. The WeChat group also arranged for legal support. Chen has said he hopes authorities will set up a union-like organisation specifically for delivery riders to negotiate on behalf of workers and platforms, and for local governments to take the lead in regulating and enforcing labour standards in the delivery industry, rather than allowing companies to squeeze delivery riders arbitrarily.

Just before the Lunar New Year in February 2021, Chen and other riders questioned Ele.me's seven-phase bonus campaign for deceiving workers. The platform's campaign lasted seven days and encouraged riders to stay and work in Beijing, rather than go home to spend the holiday with their families. However, riders found it difficult to complete the sixth phase of the campaign because of the increased difficulty of the goal, resulting in their failure to reach the full bonus of 8,200 yuan. On 19 February, Ele.me's official microblog publicly responded to the issue, apologising to riders and promising to compile a list of all orders with deviations and providing additional compensation activities. Yet Chen was arrested on 28 February. On 2 April, the Beijing Public Security Bureau charged him with "picking quarrels and provoking trouble." His family received a formal arrest notice the same day. Chen then vanished. More than ten months later, on 3 January 2022, he released a 34-second video on WeChat, implying his release.

The suppression of workers' self-help groups, combined with the influx of unemployed workers to food delivery platforms during the pandemic, have both intensified competition within the industry and also weakened the collective power of workers. Many delivery riders who have recently joined platforms and never experienced the higher pay conditions of several years ago and the subsequent wave of price cuts do not experience the same strong dissatisfaction with low wages. Moreover, many new riders see the gig as a short-term job and are reluctant to risk expressing dissatisfaction with the platform's measures, such as price squeezes and fines. Dissatisfaction, which was once high, has thus been repressed, and the number of collective worker actions has begun to decline considerably in recent years (see chart, above).

VII. State Regulation and the Role of the Trade Union

National Policy Guidance on the Platform Economy

Since China's reform and opening, the state and capital have been intertwined, and this is apparent in China's tech industry especially over the last decade. For example, the state requires social media companies to conduct their own content moderation and entire categories of content have been banned by the state, IPOs have been halted, rules on gaming have limited hours of online operation, and the companies have been enlisted to donate large sums toward political campaigns. Although there has been a global trend toward regulation of tech giants, the regulatory environment in China, including over labour standards in the platform economy, is more promising for workers.

On 16 July 2021, several national ministries and commissions joined together to adopt the first national guidance regulating platform companies. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Transport and All-China Federation of Trade Unions, and eight other ministries and commissions published the "Guiding Opinions on Protecting Labour and Social Security Rights and Interests of Workers Engaged in New Forms of Employment." This document is an attempt at comprehensive regulation of platform employment and ameliorating some of the shortcomings of existing laws to protect workers' rights and interests.

On 26 July 2021, guiding opinions specific to the food delivery industry were adopted. Seven departments jointly issued the "Guiding Opinions Concerning the Implementation of Food Delivery Platform Responsibility to Effectively Safeguard the Rights and Interests of Delivery Workers," which prohibited delivery platforms from using the "strictest algorithm" as an assessment requirement, relaxed delivery time frames, and required platforms and third-party partners to provide social insurance to delivery riders under labour relationships.

On 30 November 2021, regulations on the ride-hailing industry were put forward. Eight departments announced the "Opinion on Strengthening Rights and Interest Protection for Employees in the New Transport Industry", which prohibits ride-hailing platforms from linking driver service scores with dispatching systems and from hindering drivers from freely choosing service platforms.

After years of uninhibited development, the platform industry took note of these regulations and began to introduce some new measures to make changes to the algorithm design and social security of workers.

In December 2021, Ele.me announced an upgrade to its rider safeguarding system, including more flexible delivery times for complex delivery scenarios. These conditions include heavy rain, temporary road closures, slow delivery of meals from merchants, and inability to reach customers. Riders can also manually request extended delivery times.

In 2022, Meituan made two adjustments. One allows riders to choose not to take new orders when they face extenuating circumstances, such as damage to their vehicles, and they can choose an option to "take orders at the same time" to manage their own delivery pace. The second change involves the calculation of delivery time to include time for "accidental events." Accidental events include slow provision of food by merchants, poor traffic conditions, and other situations outside the driver's control. The purpose of the new calculation is to reduce the likelihood of a rider timing out of their allotted delivery time.

For the ride-share platforms, the government has required platforms to allow drivers to take orders across platforms. Not only does this alleviate the problem of a shortage of customers in some areas, but also it allows drivers to have more income opportunities. However, this policy may result in extending driver's working hours in practice. The current requirements for mandatory breaks for drivers on platforms such as Didi Rider may become meaningless as a result, because platforms cannot guarantee reasonable rest times for ride-share drivers without data sharing among the platforms. However, the regulations now prohibit incentives that entice drivers to disregard break times, such as Didi Rider's bonuses for rushing in to take additional orders.

Many platform workers do not have social insurance or work injury insurance as a result of the lack of formal labour relationship. According to 2021 data, the number of people employed in China's urban areas was 468 million. At the end of 2020, there were 283 million people insured by work injury insurance nationwide. From these two data points we can infer that about 200 million employed people in urban areas do not have workplace injury insurance, and that flexible employees in the platform economy likely account for the bulk of the uninsured.

The July 2021 Guiding Opinions pointed out the problem of lack of labour relationships and the resulting management issues. The regulations require written agreements with workers to "reasonably determine" the respective rights and obligations of the enterprises and workers. In April 2022, a court ruled that Ele.me should compensate a rider more than 1.09 million yuan for an accident on the job, pointing out that the two parties had established a "new type of employment relationship" through the internet that was in line with the characteristics of a traditional employment relationship.

The case of the Beijing-based delivery worker surnamed Han who died suddenly while delivering food at the end of 2020 shows the importance of work injury insurance for platform economy workers. Immediately after the incident and the media attention on the case, Han's family only received 2,000 yuan of compensation and 30,000 yuan of business accident insurance from Ele.me. Han's wife became the sole earner of the family. Their two sons' tuition fees total 50,000 yuan per year, and Han's in-laws have a monthly pension of only 200 yuan. Pressured by public sympathy for the family, Ele.me eventually gave Han's family 600,000 yuan in compensation. However, the compensation for such a work-related death should have been more than 900,000 yuan. Ele.me offered the compensation outside of its legal obligations, which in some ways is commendable, but platform companies have all along taken advantage of legal loopholes to avoid providing basic labour rights to millions of workers. Han's family is the exception.

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions

China has one official trade union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), which has a hierarchical structure that mirrors the state governance structure. Unions within enterprises are affiliated with the ACFTU, and unaffiliated unions are not tolerated. Various labour laws outline the role of the ACFTU in organising workers and defending their labour rights and interests (see CLB's 2022 report on the union's rights defence departments) to the exclusion of other entities or independent organising. The ACFTU is a bureaucratic organisation and has been urged from the highest levels to reform and genuinely represent workers' interests.

The recent rise of the platform economy has coincided with these reform efforts, and the ACFTU has begun to pay attention to the membership status of platform workers and casual workers. ACFTU leadership has, on different occasions, emphasised the need to "promote union building" among four priority industries of freight, courier, ride-hailing and food delivery, and specifically at China's leading platform companies, with the goal of strengthening regional industry trade union federations.

In addition, platform workers are included in what the ACFTU calls the "eight major groups," and the union is increasing efforts to build union membership of such workers. However, the AFCTU's organisation of union membership among the eight major groups, including food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers, still relies on the bureaucratic model of enterprises setting up ACFTU-affiliated unions on their own initiative. This is problematic in that the regional industry unions rely on the existence of enterprise unions to function, and of course that enterprises have little incentive to have a worker union in the first place. In addition, the enterprise union would be based in the location where the company is headquartered. Therefore, workers in Beijing for a platform company based in Shanghai would be unlikely to join - or perhaps refused membership in - the enterprise union. If a company's management is unwilling to set up a union, the delivery workers in that company have no way of establishing their own enterprise union or joining a sectoral or other union.

For example, after the death in December 2020 of the worker surnamed Han, the Ele.me delivery rider in Beijing referred to above, China Labour Bulletin called the service station of the Sunhe district union in Chaoyang, asking whether there was a local union of delivery workers. The union staff member responded, "Because our union set up is done through enterprise union establishment, and individuals or collectives cannot form unions."

Meanwhile, following the protest of the delivery worker surnamed Liu in Taizhou, Jiangsu province, China Labour Bulletin interviewed the Taizhou City Hailing District Federation of Trade Unions. The district union pointed out that because delivery companies have not unionised locally, the district union did not have a voice in the matter. As a result, the union had no role during the 18 days from when worker Liu discovered his wages had been withheld to when he set himself on fire.

Even if enterprises have organised unions, the union federations that are supposed to represent couriers and delivery workers to fight for better rights and interests are often chaired by the local federation of trade unions, and a string of vice chairpersons are all managers and bosses appointed by the regional union. Union committee members are not elected by the general assembly. Although the trade union established in this way has completed the eight major groups' establishment and membership targets and tasks assigned by the ACFTU, it is impossible to strive for improved treatment and protection on behalf of the employees in the industry. Moreover, since union membership is on paper only and workers do not pay dues, unions are dependent on higher-level union allocations for resources. In some cities, the delivery workers' union has no funds or limited funds, which makes it difficult for the union to organise activities for its members.

China Labour Bulletin also found that unions use the excuse that platform and third-party contractors are not located in the same jurisdiction to suggest that the union is not responsible for organising workers and protecting their rights. This excuse turns on the issue of company registration. Even after enrolling for membership in the local union, some courier and food delivery workers were rejected. The reasoning was that the platform company's head office is not registered in the union's region, so the union cannot intervene in the matter.

Rather than proactively contacting platforms and intermediaries to engage in collective consultation in line with China's labour laws and recent government regulations, unions simply push the argument that they have nothing to do with companies headquartered elsewhere. In addition to concealing the fact that unions have not organised workers within their jurisdictions, this tactic also is a poor excuse in the age of online communication that would enable unions in different regions to cooperate in bringing companies to the bargaining table. And although some unions do provide workers with various types of assistance, they do not address root causes of worker grievances or engage in collective consultations at the industry level.

VIII. CLB Recommendations

China's labour laws were designed to guarantee that workers have a minimum standard for their working conditions, including working hours, workplace safety, social security, work injury insurance, and other matters. Platform companies have taken advantage of exceptions for workers who have the bargaining power to control their own labour conditions, when in fact platform workers are coerced into clicking away their rights and work at the mercy of algorithms. Some recent regulations of platform companies show that the authorities are aware of the serious problems affecting workers and that the state can regulate this economy. However, as with China's basic suite of labour legislation, adequate enforcement is sure to be a problem.

China Labour Bulletin believes that China's official trade union and its focus on the eight major groups, including some categories of platform workers, has an important role to play in guaranteeing the rights of platform workers. In our 2019 report on the ACFTU's reform initiative, we suggested that trade unions should develop various forms of membership based on the characteristics of industry employment, in order to facilitate collective bargaining in the industry. Specifically, in terms of unions for platform workers, we recommend the establishment of unions for online platform workers with different industry union subdivisions:

These platform industry subdivisions should:

- Allow for direct, individual union membership for workers. Workers should be involved in the work of the union, and payment of dues directly to the union on a monthly or annual basis would establish a level of accountability and basis for such worker participation.

- Engage in collective bargaining with platforms to determine fair piece-rate price standards based on different goods, routes, and road conditions, and to set limits on continuous driving time.

- Call on regional unions to be responsible for coordinating and arranging the payment of social security contributions by the employing entity for members of the union to ensure that workers can start work with social security coverage.

- Engage with insurance companies to provide discounts on insurance premiums for voluntary insurance coverage, such as vehicle insurance.