CLB Report: Waiting for Weiquan: Worker rights protection at the All-China Federation of Trade Unions

08 August 2022CLB investigates the role and effectiveness of rights defence (维权 weiquan) departments of China’s official trade union. This report was originally published in Chinese and has been adapted for an English-language audience in a downloadable pdf here. The full text is reproduced below, easily navigable by clicking on sections of the Table of Contents.

Photograph: Robert Way / Shutterstock.com

I. Introduction

A. Background on the All-China Federation of Trade Unions

B. China Labour Bulletin’s research methodology

II. Changing Environment of Legal Services Amid Rising Labour Disputes

A. Legal institutions have long been unable to guarantee the most fundamental of workers’ rights

B. Available means of legal services for workers and increased role of trade union

C. Rights protection is equated with outsourced lawyers and is out of touch with workers

III. The ACFTU is a Major Legal Services Provider But Routinely Turns Workers Away

A. Most common excuses from the union on why it cannot help individual workers

B. Unions lack robust worker outreach programs

C. Unions push rights protection work to labour arbitration procedures

D. Unions limit themselves in the services they choose to provide

E. Unions refuse to intervene in the most egregious injustices

F. Unions reject requests for legal aid and workers pursue cases on their own

IV. When Local Unions Step In to Protect Workers’ Rights, Workers Quickly Find Justice

C. District union called for a multi-party negotiation that won workers’ wages in Shenzhen

V. CLB Recommendations for the ACFTU to Effectively Defend Workers’ Rights and Interests

VI. Conclusion: The ACFTU Must Broaden Its Scope of Rights Protection Work

You can also download the report as a pdf.

A. Background on the All-China Federation of Trade Unions

Since 2013, Xi Jinping has repeatedly called on the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) to help workers realise the “Chinese Dream.” In November 2015, Xi Jinping personally demanded the reform of the ACFTU, with the aim of making trade unions the representatives of workers that safeguard workers’ legitimate rights and interests. This initiative was announced as part of a series of reforms involving all of China’s mass organizations. Nearly a full year after the initial announcement, Xi Jinping said during a meeting with ACFTU leadership that the union’s work should be “centred on workers,” and that it should “seize hold of the most direct and real problems concerning their interests.”

In tandem, China’s leaders have also called on the ACFTU to improve its rights protection (维权) work. As a result, local trade unions have devoted more resources to rights protection services in response to trade union reforms, such as setting up trade union hotlines, creating trade union apps and domestic social media accounts to reach more workers, and integrating legal aid platforms to participate in labour dispute resolution.

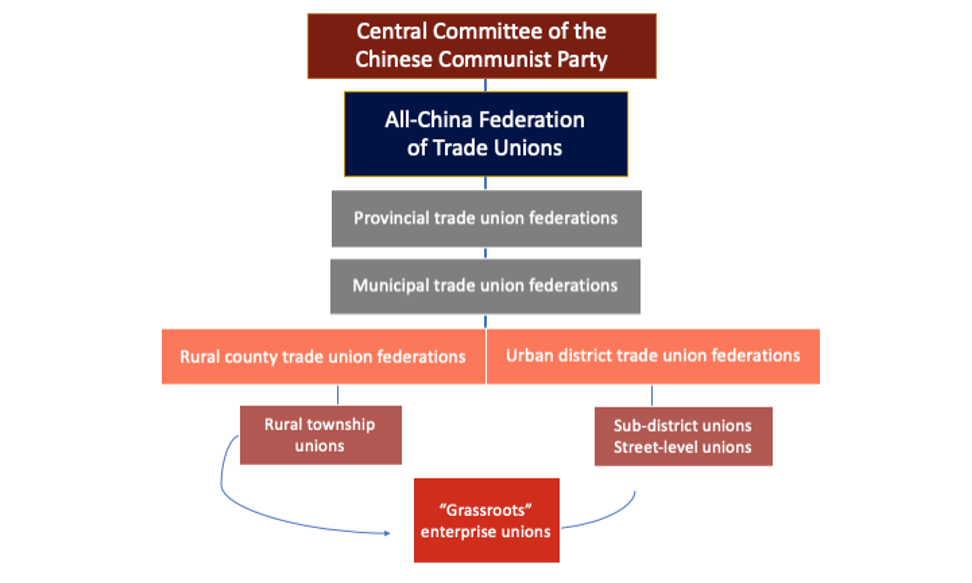

With an estimated 300 million members and one million full-time officials, the ACFTU is the world’s largest national trade union. The union has a hierarchical structure that mirrors the state governance structure, with federations of the ACFTU organized at the provincial and municipal levels. Lower-level unions are organized in urban areas at the district, subdistrict, and often street levels; and in rural areas at the county and township levels. In workplaces, unions organized at the enterprise level are all affiliated with the ACFTU and are subject to the union’s geographic jurisdiction.

Organizational Structure of Trade Unions in China

The ACFTU is China’s sole legally-mandated union - meaning that independent unions are not tolerated by the state - and is therefore uniquely placed to improve the pay and working conditions of a significant proportion of the global workforce. However, the ACFTU has rarely been a staunch advocate for workers. Instead, as a “mass organization,” it has traditionally seen itself as a servant of the Chinese Communist Party (Party), dedicated to ensuring “harmonious labour relations” and smooth economic development for the nation.

For the ACFTU to achieve high-level goals for its reform and worker representation, the Party stressed that the union had to eliminate “four impediments” to its work: regimentation, bureaucratisation, elitism and frivolousness. At the same time, the union must “increase the three positive attributes” of political consciousness, progressiveness, and popular legitimacy. This jargon means that the ACFTU should change its bureaucratic ways and focus on concrete measures that can help workers. The Party identified these core problems of the ACFTU’s dysfunctional operations and told its leaders to get it fixed. The Party’s assessment provides the foundation for genuine reform of the trade union’s role and operations.

B. China Labour Bulletin’s research methodology

To monitor the ACFTU’s progress and to advance trade union reform from the ground up in a worker-centred manner, China Labour Bulletin (CLB) began a trade union reform and accountability program in 2018. In this report, we utilise actual cases of workers’ rights disputes and our phone calls with local unions to analyse how effective the ACFTU’s rights protection departments are in safeguarding workers’ rights.

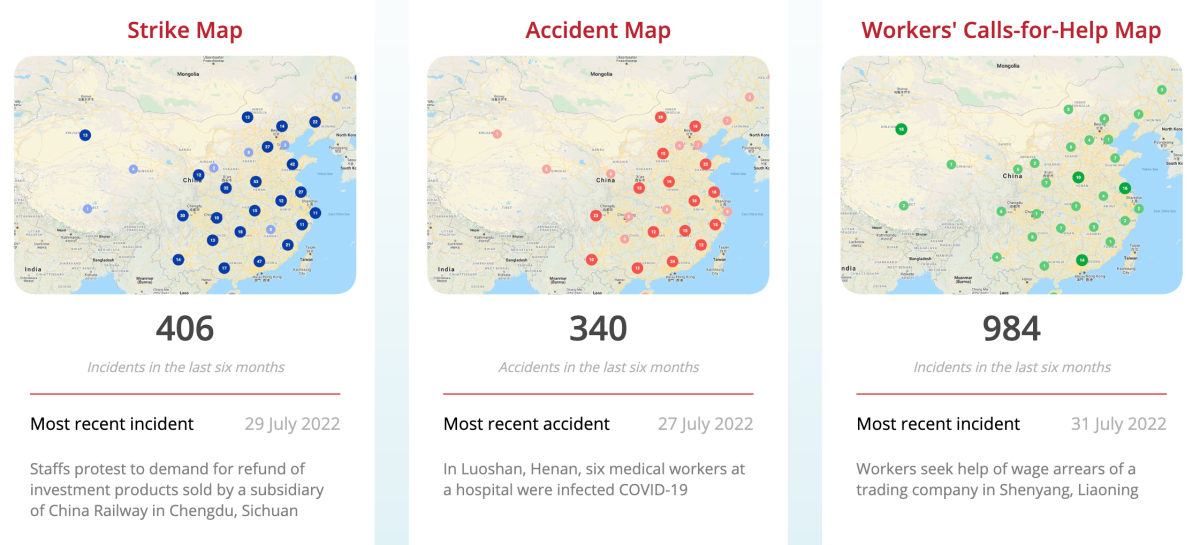

CLB has three databases from which we regularly select incidents about which to interview ACFTU officials. Our Strike Map was created in 2011 to document workers’ collective actions, such as strikes, road blocks, and protests. In 2014, we created a Workplace Accident Map to log accidents and injuries that occur on job sites in China. And in 2020, we launched a Workers’ Calls-for-Help Map that collects individual labour disputes of workers. After selecting specific incidents, we make calls to the local trade unions operating in the areas where the incident occurred. We ask the officials if they are aware of what happened, if they are willing to respond, and how they view the role of the union in the context of each dispute. CLB writes periodic reports on these investigations, and we have compiled the data that results from these investigations into a fourth map (available in Chinese language only) the Trade Union Reform and Accountability Map.

China Labour Bulletin’s Mapping Projects

CLB’s project is ongoing, with new cases investigated regularly. From October 2018 to December 2021, we investigated 127 cases. For most of the cases, we interviewed more than one trade union, such as the district level union, municipal level union, sectoral union, etc., or more than one union department, such as the union’s organizing department or the union’s rights defence department.

Among the 127 cases we investigated across the country, trade union officials in 77 cases (61 percent) were completely unaware of the worker incident; in 47 cases (32 percent), the union had knowledge of the incident; and in 3 cases we did not receive a response on this question. We also found that in 89 cases (70 percent) the trade union was uninvolved in the worker incident, and in 31 cases (24 percent), the union had some involvement.

In some instances, the union did not initially know about a case, but after CLB’s interview alerting them of the situation, the trade union took up the case. Although these account for only nine percent of the 77 cases of union lack of awareness, it is a welcome start. Among the 47 cases in which the trade union was already aware of the case, there were 19 cases in which the trade union knew of the incident but never participated, and the remaining 24 cases were those in which the trade union was able to participate (accounting for more than 51 percent).

Based on CLB’s data collection and interactions with workers over decades, we know that workers in the vast majority of cases do not actively seek help from the trade union, workers do not have a trade union as a representative in their disputes, and most of the workers have never joined a trade union. Workers often tell us, “I don't know the functions of the trade union, and I don't know how finding a trade union can help resolve my demands.”

Photograph: hxdbzxy / Shutterstock.com

And even if the workers do contact the union, the union seems unable to find a way to help them the majority of the time. In our interviews, trade union officials readily admit that the ACFTU is still subject to its bureaucratic structure, and it is not equipped to effectively organize workers and represent their interests. Most trade unions have rights protection departments, but they are unable to effectively protect the rights and interests of aggrieved workers.

In this report, we first provide background on labour disputes in China and the more prominent role of the ACFTU in the landscape. Then, we present our research findings that the ACFTU routinely uses several of the same excuses to turn away workers seeking assistance. The union outsources most of its rights protection work to lawyers who also turn workers away based on cursory assumptions about likelihood of success in formal legal proceedings, and workers are often left to fend for themselves.

However, we have also found that when the union opens its doors to workers and responds to their requests, it can be very effective at quickly bringing about positive results for workers. In our report, we describe some of these positive examples. In addition, based on our analysis, the ACFTU’s recent focus on eight major groups of workers - together with their persistent focus on construction workers and migrant workers - will be an important test for the overall effectiveness of the union at protecting workers’ rights, including before violations occur. We conclude the report with recommendations for the union at its various levels.

II. Changing Environment of Legal Services Amid Rising Labour Disputes

A. Legal institutions have long been unable to guarantee the most fundamental of workers’ rights

Yang Fazhang was a carpenter working on a government-funded shanty town renovation project in Panzhou, Guizhou province. He and his co-worker were owed more than 60,000 yuan for a year’s work, starting in October 2019. He had not signed a labour contract, but he had an oral promise that he would be paid.

Born in 1985, Yang attended two years of school and could no longer read. Still, he managed to file a lawsuit that the court rejected on the grounds that it was not an issue on which the court could rule, and in the end, Yang signed a legal document he did not understand. He then went to the labour dispute arbitration commission, which also refused his case. Later, after CLB’s intervention, the union came to his aid. But without the union’s assistance, Yang’s story would have ended with this legal dead end.

The inaccessible legal system affects a wide range of workers. In December 2021, a graphic designer surnamed Liu was working at a gaming company and was made to do tasks outside the scope of his designated role and to work a 996 overtime schedule. The company he worked for was very small, consisting only of a producer, a manager and a human resources staff.

When Liu asked to work regular hours and get paid for overtime - according to the Labour Law - his company denied his request, accused him of not fulfilling his duties, and extended his probation period for another month, meaning that he was paid 20 percent less than his promised salary.

Photograph: Robert Way / Shutterstock.com

Liu left the company before the end of his probation period and filed a labour arbitration claim against the company. Liu submitted all kinds of records to try to receive compensation for his overtime work, but the arbitration went in his company’s favour. The court said that Liu should have applied for overtime and that the extension of probation merited a payment to him of only 500 yuan.

“It’s laughable,” Liu said. “My many records lost against a few words with no evidence to back them up.” At that time, he was paying 2,000 yuan in rent, and the labour arbitration process had stretched to three months.

Liu is a white-collar worker with a decent education who was able to stand up for himself in the workplace and leave his job when his rights were violated; how much more difficult for the vast majority of China’s workers making minimum wage, without labour contracts, living as rural migrant workers far from home, and with families dependent on them?

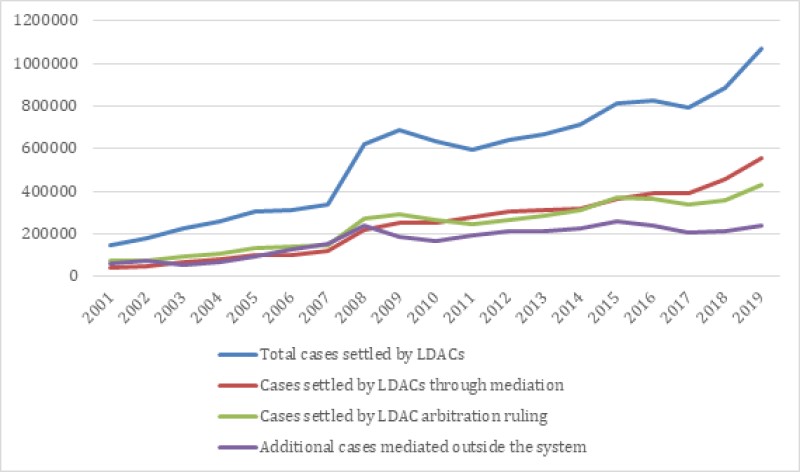

The principal institution for resolving labour disputes is the labour dispute arbitration committee (LDAC). LDACs handle the majority of routine labour disputes in China, as an employment case must first go through this dispute resolution mechanism before being entertained by the civil courts. The process of submitting a case to the LDAC is relatively straightforward and inexpensive for most workers, but the outright win percentage for workers in the LDACs in 2020 was just 28 percent, with 61 percent of cases resulting in a compromise ruling, according to the China Statistical Yearbook (2021).

The number of labour dispute cases in 2020 reached 1.09 million, involving more than 1.28 million workers, the highest since the Labour Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law was introduced in 2008. Of these cases, 552,584 were settled by mediation and 430,309 by arbitration ruling. Arbitration claims must be filed within one year of the incident from which the dispute arose.

Number of cases settled by labour dispute arbitration committees (2001-2019)

The main types of disputes brought to LDACs are compensation disputes (462,000 cases, or 42.2%); labour contract and termination disputes (280,000 cases; 25.6%); and social insurance disputes (136,000 cases; 12.5%). These types of disputes are over the most fundamental labour rights and benefits of workers, showing that actually obtaining these basic benefits guaranteed by law is still difficult for a large number of workers.

An appeal of an arbitration ruling is heard in civil court, in accordance with civil litigation procedures. In disputes arising from an employer’s decision to terminate an employee, reduce remuneration, or recalculate length of service, the burden of proof lies with the employer. The disadvantage for worker-plaintiffs is the financial cost and time of court proceedings. Even in basic labour dispute cases, workers pay legal fees of at least 5,000 yuan.

In addition to financial cost, workers often have to spend a lot of time in litigation, including gathering evidence, consulting with lawyers, and going to court for hearings. According to a 2013 report from the Yilian Legal Aid and Research Center of Labor in Beijing, cases of occupational illness could take up to 1,926 days, or over five years.

And in the end, even if the worker wins the case, there is no guarantee the judgement will be enforced against the employer.

Another problem is that some categories of workers and claims are not accepted by LDACs and must start in civil courts. In June 2021, a student who was working at a media company in the capital of Hebei province found that after apologies and promises that his salary would be paid, the company just disappeared. Though the student reported his issue to the district’s labour inspectorate and other authorities, they said that his status under the university’s work-study program meant that he did not have a legal labour relationship with the company, and they advised him to find a lawyer.

“Bringing this case [in civil court] costs 5,000 yuan, which is more than my salary,” the student said. “If I could afford a lawyer, why would I still be working and studying?”

B. Available means of legal services for workers and increased role of trade union

In a 2016 report entitled, Who Will Represent China’s Workers?, Aaron Halegua comprehensively outlines the landscape for representation of workers’ legal claims according to the environment at the time of writing. Halegua discusses the availability, cost, and effectiveness for workers of China’s private lawyers, the formal legal aid system, legal aid provided by the trade union, pro bono services by law firms, “barefoot” lawyers, basic-level legal workers, law school legal clinics, bar associations, and labour rights NGOs.

Since that time, the landscape for worker representation has changed dramatically, from the effects of the “709 crackdown” on rights lawyers in 2015, the increasingly sensitive political environment affecting lawyers representing groups of plaintiffs, and the shuttering of law school legal clinics and many labour NGOs. In a 2022 publication, Halegua describes these events as contributing to a “legal pre-emption” strategy of the state to channel labour issues through official legal procedures, rather than allow for collective or independent means of dispute resolution.

In fact, in 2015, the State Council issued opinions on improving the legal aid system and instructed the Ministry of Justice to focus its legal aid on migrant workers and laid-off workers. The ACFTU followed suit in September 2015 by requiring all levels of trade unions to increase their provision of legal aid to workers. This included targeting industries with a high frequency of labour disputes, vulnerable workers, and cases of wage arrears and workplace accidents and illnesses. In addition, the ACFTU notice stated that unions should make efforts to accept, assess and handle applications made by vulnerable workers within one day’s time.

For context on this ACFTU directive to its lower unions, according to Halegua:

The ACFTU reported that between 2011 and 2015, it had provided free legal representation to workers in arbitration or litigation in 250,000 cases and participated in the mediation of 1.5 million labour disputes… The number of actual cases handled by the trade union legal aid offices seems quite low in light of the reported number of personnel, however. The official statistics for 2012… state that over 36,000 staff, including 3,537 credentialed lawyers and over 55,000 volunteers, only handled 66,000 cases. This means less than two cases per staff member and less than 11 labour dispute cases per lawyer each year. (p. 30)

Therefore, there is plenty of room for the ACFTU to improve its record, and the instructions to China’s unions to increase their legal aid and focus on certain categories of workers and labour rights grievances are straightforward. The more prominent role of the trade union in providing legal aid for workers and the more recent absence of other viable alternatives necessitates a better understanding of the trade union’s progress on providing legal assistance to workers.

C. Rights protection is equated with outsourced lawyers and is out of touch with workers

"Where the legitimate rights and interests of workers are violated, the trade union must speak out."

—Xi Jinping, speaking in 2018 to the new leadership of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions

Under the trade union reform initiative, local trade unions have set up special departments to help workers with their rights disputes. In this report, we refer to them as rights defence departments (维权部), but the names of these departments within each local trade union are not uniform. This confusing nomenclature makes it difficult for workers - and for CLB - to contact the appropriate personnel.

According to our telephone interviews, the offices can be referred to by over a dozen different names, a few of which are: the safeguarding rights and interests department (权益保障部), rights protection department (维权部), legal work department (法律工作部), economic and legal department (经济法律部), etc. Sometimes, rights protection services also belong to the workers’ rights protection hall (维权大厅), the employee petition department (职工信访部), the employee assistance centre (职工帮扶中心), the employee service centre (职工服务中心), the migrant worker committee (农民工委员会), etc.

The union officials who work in these departments have several roles. They publicise labour laws among enterprises, check the labour standards of the enterprises with administrative departments, hire lawyers to explain labour laws, and contact judicial and administrative departments to handle specific cases. They also participate in trade union activities, including publicity and public education.

When individual workers seek union assistance in protecting their labour rights, some local unions will receive these workers and register their cases with the union. If the union has the resources, it will outsource lawyers to provide legal advice and aid. For example, the Shenzhen federation of trade unions has had a legal services purchase model since 2014.

In fact, most trade union officials perceive rights protection and legal services as a “very professional matter” and that the union itself does not have the required legal knowledge or qualifications to advise workers themselves. One union official working in the legal services department of the Liyang city union in Jiangsu province told us:

In terms of legal aid, this requires a lot of professional legal knowledge, and we don’t have these qualifications. I can only say that we have to depend on the justice bureau who does this work through lawyers and who have their legal aid service. Then, within the enterprise, we can examine the labour rights condition by examining the documents that need to be checked, such as labour contracts. But again, we do not have the expertise in this regard. We have to rely on labour bureaus and the labour inspection team for help on these checks, or when there are work-related injuries. We can only stay within the scope of our abilities, but we can find someone to help workers. For example, if you ask me for this knowledge but I don’t understand it, then I can use my status as the trade union official to seek help from other departments.

Perhaps it is understandable that union officials are hesitant to offer advice that could be misconstrued as professional legal advice from someone not qualified to give it. In that case, we would expect the lawyers to be able to handle the workers’ individual cases. However, in our conversations with various union lawyers, we also found their ability to apply the law to the facts of workers’ situations to be lacking. The lawyers have professional knowledge - they can always cite the relevant labour laws - but their suggestions to workers are based on the legal framework and not on the specifics that the workers presented or the evidence at hand. This is compounded by time constraints, and the lawyers only want to pursue the cases they believe at first review to be most likely to succeed.

Although the union services are increasingly professionalised, this also limits the scope of the union’s work. Many unions believe that executing their rights protection duties simply means hiring lawyers to provide consultation and legal assistance to workers in need. Unions tally the number of consultations provided, the number of workers assisted, and the amount of compensation won on behalf of workers, and this data often lacks context or qualitative assessment.

The role of the union should be to represent workers in resolving their labour disputes, and this representation is more meaningful than the outcome or objective success of an individual case. There are a number of methods the rights departments could use to organically link their work to that of the union as a whole. For example, the effectiveness of the trade union is often assessed in terms of increase in membership of workers, but could be assessed by the ability to increase minimum legal standards for workers, to form collective contracts in different industries, and otherwise make improvements across the board rather than only in individual cases. In other words, instead of post hoc remedies, the union could advocate for conditions that protect rights and prevent violation of those rights before they occur. In other words, the needs of workers go well beyond the ability of unions to provide legal services.

III. The ACFTU is a Major Legal Services Provider But Routinely Turns Workers Away

The role of the trade union in providing legal aid for workers is more prominent in the recent absence of other viable alternatives. Based on CLB’s recent experience of assessing the union’s track record on representing workers in our trade union reform and accountability program, this report takes a case-based approach to understanding the trade union’s progress on providing legal aid to workers, particularly since 2018 when we began our investigations in full force.

A. Most common excuses from the union on why it cannot help individual workers

As union legal aid services have become more professionalised and outsourced to lawyers, we found that the union still sets the scope of what services it provides and to whom. The union acts as a gatekeeper and will help some workers, but it often turns workers away. We have categorised the most common reasons that unions give for refusing to help workers:

- Workers are not union members; the union cannot provide services to workers who are not members of the union.

- Workers are not covered by the jurisdiction of the union they are requesting services from; the case belongs to a different union.

- The union lacks the authority to intervene in the case; the worker should seek assistance from administrative departments instead.

- A worker’s request exceeds the scope of the trade union’s services; for example, the union will not take on a criminal case, a case after a worker’s legal retirement age or actual retirement, or an administrative case, etc.

- The union’s bureaucracy prevents the union from taking action in the case; the union deflects responsibility onto another union level or department.

When we contact unions about workers’ cases, almost every conversation involves the union attempting to deflect responsibility and pass it off to another entity, typically a higher-level or lower-level union, or a union in another geography.

For example, in early 2020, taxi drivers were protesting in Hebei province. Some of these protests were occurring in Renqiu, a county-level city outside of Cangzhou. We contacted the Cangzhou municipal federation of trade unions, and staff at several different union departments said they had not heard of the protests. Despite the protests having a wide scale, the officials emphasised that the case should first be referred to a lower-level trade union in Renqiu.

Photograph: Rob Crandall / Shutterstock.com

We next called Langfang municipal federation of trade unions, because taxi drivers were also protesting in Langfang. Langfang is a prefecture-level city also located in Hebei province, just to the north of Cangzhou. Various departments within the union also deflected. The staff had not heard of the taxi drivers’ protests, and the union’s organizing department suggested that the workers contact the union themselves.

However, the Langfang union officials also said that after institutional reform, the union no longer takes up petition cases and that the administrative department for petitions should handle the case. The grassroots work department of the union said that it had not received any inquiries from the taxi industry and could not verify whether the protests were occurring, deflecting the matter by saying they needed to verify the situation first.

This is just one example of the run-around we receive from unions when trying to investigate a simple matter of whether the union is aware of worker grievances and can do anything to help resolve the problem.

B. Unions lack robust worker outreach programs

At the end of 2020, a food delivery driver surnamed Han suddenly died while delivering orders for Ele.me, one of the two largest such platforms in China. This incident happened in Beijing, and Ele.me is headquartered in Shanghai. In its early response, Ele.me insisted that it had no labour relationship with dispatched workers, but that it would compensate Han’s family 2,000 yuan as “humanitarian assistance.”

We called the trade union at the district level in Beijing where Han was dispatched. The Sunhe union service station in Chaoyang district stated that the union can only serve union members, and it was not clear whether Han belonged to the union. The official also stated that Ele.me is such a large company, so the case “cannot be managed by our regional federation of trade unions.”

But from the worker’s perspective, how could a Beijing delivery worker possibly attempt to join the union in Shanghai where Ele.me is located, and how could his family now contact anyone in Shanghai for resolution of this matter?

Photograph: YPPicturesPro / Shutterstock.com

In addition, the company denied a labour relationship with Han in Beijing. The question of which entity is responsible may be up for debate, but what should not be contested is that the worker is entitled to union representation for his labour rights, and the union is in the best place to help his family navigate the situation.

Trade unions are still largely waiting for companies to set up an enterprise union first, and the union is not organizing workers from the bottom up. But from the worker’s perspective, if the corporation has an enterprise union, this enterprise structure cannot cover every area where services are provided across the country. Therefore, how would delivery workers join the union in the first place, and why are unions not willing to represent food delivery workers in their districts regardless of the membership issue?

The reality is that food delivery workers and other workers of online platforms face barriers to joining unions, foreclosing union representation. In another case, we called the Fuzhou municipal federation of trade unions about unpaid wages to package couriers in Fuzhou city, Fujian province. Couriers for YTO Express were protesting unpaid wages there. The trade union officials informed us that YTO had established an enterprise union in Fuzhou, but restricted its membership to direct employees only. Therefore, couriers organized below the franchise level were not eligible to join the enterprise union, and there is no union for couriers to join in Fuzhou.

We suggested that the union go ahead and negotiate with express delivery companies, but the union stressed that the workers should be union members before the union can step in. Otherwise, the workers must go to administrative departments or through legal channels. It turns out that the union used the difficult reality couriers face as their best excuse for not conducting any outreach to workers. If couriers cannot join the union, then we believe it must be a priority for the union to settle this issue and provide opportunities for union membership. But instead, in one breath, the union closed its doors to almost all couriers in its city.

C. Unions push rights protection work to labour arbitration procedures

Danke is an apartment rental service that is popular with mobile populations. The company, which is headquartered in Beijing, outsources a variety of types of labour across the country. Danke’s labour practices leave its workers with few labour protections, and the company’s bankruptcy in late 2020 caused many workers to go unpaid with no recourse.

For example, cleaners of Danke apartments in Hangzhou had wage disputes since 2019, and one worker in Wuhan wrote online, “We eat the worst food, live in the cheapest apartments, work the longest hours, and have to clean the dirtiest apartments. Please pay your cleaning staff.”

Photograph: Graeme Kennedy / Shutterstock.com

White-collar workers at Danke were also affected. Workers were surprised to learn that the labour contracts they signed electronically were inaccessible after the company’s bankruptcy led to the employee platform being shut down. And contractors who renovated Danke apartments went unpaid, making them liable to their construction and renovation teams for millions of yuan in wages.

Not only did workers protest against their wage arrears outside Danke’s headquarters in Beijing, but also customers of the company who paid rent and were left without housing joined in demonstrations.

CLB contacted the Dongcheng district federation of trade unions in Beijing to ask whether the union could represent the interests of workers affected by Danke’s bankruptcy. The union officials of the legal services department said that the labour department had become involved and responded to employees’ demands. The officials said that the union maintained communication during the arbitration. We asked the union whether it could assist Danke employees in getting their wages, and the official responded, “Haven’t they entered the arbitration process now? Isn’t it over after going through the process and waiting for the arbitration result?”

As far as the union is concerned, the labour dispute can be resolved through arbitration or civil proceedings. We often find that the union acts in this way, choosing to let workers and employees navigate the situation on their own through the legal channels, without considering that the union could have a role to play before legal procedures are necessary. In addition, the bargaining power of workers and their employers are unequal throughout the process, so the union could step in to ensure a measure of fairness.

If administrative and legal departments are the only ones suited to handle labour disputes, then what is the purpose of the union at all?

D. Unions limit themselves in the services they choose to provide

In late April 2021, a tutor with physical disabilities posted online that she was rejected for her teacher qualification certificate in the city of Chongqing after failing a physical examination that required her to walk unaided. The situation of this tutor, surnamed Zou, immediately attracted public attention.

National government regulations for teachers require a physical examination that includes screening for infectious diseases and mental health history, but there is no stated requirement for teachers’ mobility. Therefore, Chongqing’s additional requirement that prevented Zou from passing her certification went beyond national law and was discriminatory.

The day after Zou posted her story, we contacted the sectoral trade union in Chongqing responsible for education, science, culture, health and sports. We discovered that the sectoral union had long ignored the government’s discriminatory policies and were reluctant to get involved in Zou’s case, using the excuse that she was a private tutor and not a teacher in a unionised public school or college.

Photograph: jianbing Lee / Shutterstock.com

“The union’s work is currently limited to Chongqing’s high schools and vocational colleges. This kind of tutoring is outside our scope, so we really have no way to help in her case,” one official explained.

Even though Zou’s story had gone viral on social media, local trade union officials claimed that they were “not very clear” about the specifics of the case.

In June 2021, Chongqing amended the policy to exempt private tutors like Zou from the physical mobility requirement. The new policy has not been made public, but we confirmed the change with a teachers’ representative in the city. And when we called the union back to discuss the policy change, the official answering the phone simply hung up on us.

The union used the excuse that Zou is not a traditional teacher, but it is tutors like Zou whose labour rights face lower protection and have a strong need for the union to come forward to assist them. In fact, we urged the trade union to include tutors in the sectoral union, in light of recent government regulations on the private tutoring industry. The trade union should take this case to help tutors safeguard their rights and attract more workers to join the union. Not only did the Chongqing sectoral union miss an opportunity to represent Zou in defending her rights, it also excludes other workers from the union.

The above examples are only a few of the examples that we have encountered from our recent interviews with trade union officials in which they refuse to help workers on various grounds. When the union categorically refuses to help workers in cases just like these, what do workers end up doing?

E. Unions refuse to intervene in the most egregious injustices

In one disturbing case, workers who were owed wages were threatened and beaten by their boss for asking for their wages to be paid. The workers defended themselves from the physical attack, but then were criminally prosecuted for assaulting the boss and served jail time. They never got their compensation. During this process, the family members of the worker-defendants sought assistance from the union, but the union said they could not intervene in a criminal case.

In May of 2020, 14 migrant workers from Chongqing began working in Liaoning province at a mining project of Fuxin Honglin Mining Group. The company did not sign labour contracts with the workers, only verbally agreeing to the terms of their payment. The boss, Liu Yuzhong, is also the legal representative of the company.

After 40 days on the job, the workers were forcibly removed from the worksite and told they could no longer work there. The workers, including Wang Xiaoming and Liu Haiquan, described how the power was turned off in their worker dormitory. This situation in itself is unacceptable, but also the workers had not yet been paid for their labour and were owed a total of 100,000 yuan. The workers called the local police, who appeared on the scene that same evening and restored power to the dormitory, but the wage issue was not resolved that night.

Photograph: Frame China / Shutterstock.com

The next morning, the boss brought three unknown individuals to the workers’ dormitory to intimate the workers. The boss offered each worker only 3,000 yuan in wages, but the workers refused to agree. Along with the hired hands, the boss also picked up a wooden stick and beat the workers. Liu Haiquan and others were knocked to the ground and suffered injuries.

Wang Xiaoming tried to use his phone to record the attack, but the boss snatched the phone and beat Wang, too, strangling him and ripping his clothes. As Wang defended himself, one of the attackers was injured. The workers were able to reach the police again and the situation deescalated, but three workers were injured, one with serious injuries.

The following day, Wang was criminally detained by the public security bureau for intentional injury. In July 2020, the local authorities called the workers into the administrative department to collect their unpaid wages, but public security took Liu Haiquan away at that time. He was also detained on allegations of intentionally inflicting injury.

The criminal trial was focused on prosecuting the workers for hurting others, without mentioning the situation of the general labour dispute, the unpaid wages, or the actions of the boss that led to the incident. The workers had evidence of their unpaid wages, the calls to the police, and their own testimony. But in the judgement, the presiding judge did not mention these factors and sentenced Wang Xiaoming and Liu Haiquan to 10 and 11 months in jail, respectively.

The workers’ families had turned to the trade union for help along the way, but the union said it was “unable to intervene in criminal cases.” This excuse ignores the fact that the criminal case is the result of a typical labour dispute about the ordinary problem of wage arrears, and that the workers were facing the extreme injustice of a criminal case for defending their labour rights in the first place.

F. Unions reject requests for legal aid and workers pursue cases on their own

Even when turned away from the union, or if the labour bureau or private lawyers advise workers that their case will not be successful in arbitration or civil court, some workers are willing to exhaust all available avenues on the road to justice.

In a case that we are reporting here for the first time, a worker with the pseudonym Qiang is a construction worker who travelled to Huizhou in Guangdong province in May 2020 for a job bonding wall and floor tile. Qiang learned about this job from a fellow villager in his hometown, and there was an oral agreement about wages rather than a written labour contract. Through the summer and autumn, Qiang received three payments for his work, each from a different legal entity.

One day, Qiang suffered severe lacerations from being cut by tile on the construction site. His manager was not on duty at the time of the accident, so Qiang went alone to a nearby hospital and paid for the medical treatment himself. The cost was more than 10,000 yuan, including hospitalisation, examinations, and transportation.

Immediately after the accident and medical treatment, the project manager dodged Qiang’s requests for medical fees. The site manager questioned whether the injury occurred while working or whether Qiang had actually gotten into a fight. Desperate, Qiang called the police for help. Because of police intervention, the manager finally admitted that the injury happened while Qiang was working on this job, and stated that the company would submit an insurance claim on Qiang’s behalf.

However, the insurance claim was never submitted, and in June 2021, Qiang was instructed by a lawyer to file a civil lawsuit for personal injury, rather than a workplace injury case. But during mediation, the employer’s lawyer promised to provide the evidence necessary to obtain workplace injury certification in exchange for dropping the civil lawsuit. Qiang agreed and withdrew the personal injury claim. However, the evidence was never provided.

Qiang then went to the local labour department and reported that the employer violated labour laws by not paying for his medical expenses or filing the insurance claim. The labour department rejected Qiang’s claim because he could not prove the labour relationship. Facing a dead-end, Qiang posted online, where we found his information.

When CLB contacted Qiang after seeing his social media post, we asked him if he had sought assistance from the local trade union. He said:

I don't know anything about the trade union. I was told to try the petition department [for administrative complaints] to protect my rights. But the government labour departments just ignored me. Maybe there are trade unions around here, but at our worksite there isn’t one. We migrant workers don’t know about the trade union. We don’t understand these things. The way we have always done it is just on our own.

CLB told Qiang that the trade unions organized at or above the county level are required to establish legal aid departments. These departments can provide free legal services to workers. Qiang said that he only knew about legal aid from the county justice bureau, and he was worried that he did not have sufficient documentation for his claim. He felt that seeking assistance would be “troublesome.”

CLB called the Huizhou federation of trade unions to see if they would reach out to Qiang. The operator referred us to the rights protection department, but no one there answered the phone.

We urged Qiang to call the union himself. When he did, they said they do not accept individual workers’ complaints and to take his case to the Huiyang district union. The Huiyang union answered his call, but after the lawyer told Qiang his case was not strong because he could not establish a labour relationship, Qiang completely lost faith in the union.

At this point, CLB called the duty lawyer of the Guangdong workers’ hotline, and that lawyer also stated in so many words that the union could not help Qiang because he likely had no chance of winning his case:

Actually, in terms of emotional feeling, the trade union is very inclined to help workers whose rights were infringed. But if their case is outside the bounds of the laws and regulations, then the trade union’s intervention still cannot help the worker… When a worker encounters challenges, it is the unshirkable responsibility of the trade union to offer help, but the reality is the union may not be able to solve workers’ issues despite us having a lot of sympathy for them. Sympathy itself cannot equal problem solving. If the worker is a union member, they can apply for some welfare or assistance from the union for comfort; but from the legal point of view, the trade union may not be able to offer more help. After all, the union is just an organization of workers and cannot be above the law, right? Just because we contact the worker and send a lawyer there does not mean that the terms of the law do not apply in that case. Then, we cannot help the case very much and the worker will be very disappointed… In fact, we can be pretty certain - I can basically tell you that there is in fact a high probability - that the worker has exhausted the legal time frame for the claim. That is, even if we contact a lawyer, what will be the biggest outcome? It will be that the worker has wasted his time and effort in vain.

This reasoning is quite circular, because if only the union would help Qiang and urge the employer to provide the evidence of the labour relationship and of workplace injury, then Qiang could indeed be successful in his legal claim. The sympathy for Qiang is meaningless with some action on the union’s part.

The lawyer we spoke to then used the union hotline to have someone at the Huiyang district union call Qiang to find out more about this situation, and that lawyer also told Qiang that his odds of succeeding were low. In the end, the union did not intervene in the case.

But Qiang did not give up. He strongly believed that justice was on his side, and he found a solution that the union lawyer had not considered. Qiang pursued his claim on his own through legal channels, and his case was accepted for labour arbitration in the spring of 2022. Qiang’s case has not yet come to a legal conclusion at the time of this writing.

Many workers with workplace injuries face a similar experience to Qiang’s. In many cases, their claims are made outside of the workers’ compensation insurance system, and work-related injury assessment and certification is a cumbersome and time-consuming process. Without a formal labour contract clearly stating the legal entity the worker has an employment relationship with at the time of the accident, it will be almost impossible for the legal system to handle. Many claims are dismissed on such a technicality, or administrative and judicial authorities are unable to enforce a judgement in the worker’s favour without proof of the labour relationship.

But this is an area where the union can effectively step in, whether that is to ensure that employers properly sign labour contracts, to assist workers in establishing the employment relationship when a problem arises, and otherwise standing with workers so that justice can be on their side.

IV. When Local Unions Step In to Protect Workers’ Rights, Workers Quickly Find Justice

Labour disputes consume a quantity of time, money, and effort that many workers and their families have little of to spare. The pressure on workers comes from the complexity of the procedures, as well as the psychological burden over the lifespan of the dispute. But if the union can intervene as soon as possible to assist workers, labour disputes could be resolved before legal channels are necessary. And if workers do utilise the legal process, the union can accompany workers along this road and share the burden.

Among the cases in which CLB has followed the union’s intervention, we found that the sooner the union intervenes to defend workers’ rights, the greater the chance that workers’ disputes will be resolved through negotiation. Early intervention also increases the trust that workers have in the union to perform the representation. Below are some examples of cases of union intervention that are models for other unions to consider in their work to represent workers and defend their rights.

A. Construction worker injured on job site in Sichuan province, union negotiates with management for medical fees and wages

In the summer of 2020, Jia Xiaohong posted online for help, saying that while working as a painter on the construction site of the new primary school in Mianyang city, Sichuan province, he slipped and fell, fracturing his leg in two places. The subcontracting boss took him to the hospital on the same day and paid 1,000 yuan in advance. After that, the subcontracting boss never went to the hospital again, claiming that he could not find the contractor to take charge, and the hospital urged Jia to pay for his continued treatment himself.

Although Jia was injured at the construction site, no one from the job came to visit him in the hospital or pay his medical expenses. Jia ended up calling the police, who told him to come into the station to make a report. At the police station, the officers told Jia that because they had no labour law enforcement power and could only mediate, they could not help him.

Jia then called the mayor's hotline and was instructed to go to the judicial bureau instead. In the end, Jia could not keep paying for the medical expenses. He defaulted on his hospital fees and had no choice but to be discharged from the hospital and forgo treatment on his leg.

Photograph: chinahbzyg / Shutterstock.com

Photograph: chinahbzyg / Shutterstock.com

CLB found Jia’s case online after he posted upon his hospital discharge. We called the county federation of trade unions, who first stated that because no preliminary work-related injury assessment had been conducted, that it would be hard to help the worker. But CLB insisted that it was this workplace injury certification that the worker needed assistance with, and we also called the municipal union to report what the county level union told us.

Within one day of CLB’s phone calls, the county union immediately contacted Jia to better understand the situation. Jia said that with the intervention of the union, his bosses and the project leaders on the construction site immediately changed their attitude of indifference. They came to visit Jia at his residence the next day to settle not only the medical expenses but also his unpaid wages. Over the course of the following month, the bosses gave Jia about 3,000 yuan to cover his medical fees.

B. Municipal and district levels of trade unions in Guizhou province coordinate with each other to help migrant workers get paid

The case of worker Yang, referenced earlier, is an example of a worker trying to navigate the system alone and facing a dead end, before the union successfully came to his aid. In June 2021, Yang Fazhang, a construction carpenter from Weining Yi Autonomous County in Guizhou province, posted online complaining about illegal subcontracting and wage arrears in government projects he was working on as an intra-province migrant in the city of Panzhou.

In October 2019, Yang and two other workers were hired by two different contractors for part of the carpentry work on a project. Yang and his colleagues worked on the project for over a year, but after completion of the job, they were not paid. The first contractor owed them 40,800 yuan in wages, and the second contractor owed them 21,000 yuan.

CLB learned of this case from Yang’s online post and called the Liupanshui municipal federation of trade unions and notified them of Yang’s problem. The staff of the economic work department responded positively: “It is the trade union’s duty to protect the rights of the workers.”

We suggested that the union could coordinate with other departments to solve Yang’s wage issue, and also for the union to proactively reach out to Yang. The official agreed: “There is no problem with this.”

After talking with that official at the Liupanshui municipal union’s economic work department, we then called the rights protection department of the same union. The staff also responded positively to our call. At first, they were concerned that, without a labour contract, Yang would have trouble asserting his rights. But we suggested that the union contact the Weining county level union or the Panzhou municipal union, which are both lower-level unions under the union’s geographic structure.

The official from the rights department agreed, saying, “I’ll contact Yang Fazhang and then I’ll look into it from the Panzhou municipal side.”

The same day that we made these phone calls, the Liupanshui municipal federation of unions reached out to Yang and also contacted the Panzhou union, which in turn contacted Yang, too. Yang let us know that he sent some documentation to the Panzhou union, who added him on social media as a means to keep in contact.

The coordination of the Liupanshui and Panzhou unions in this request for assistance with unpaid wages is commendable. Since their intervention, Yang was paid his full salary.

In addition, the unions have promoted their assistance to Yang as a model for how unions should approach their work. In an article highlighting the Panzhou union’s work in this case, the union wrote that it is paying attention to the protection of rights and interests of workers and promoting harmonious labour relations: “We made every effort to safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of migrant workers, organized and carried out the legal services provisions… and actively cooperated with relevant departments to solve the problem of wage arrears of migrant worker Yang in Weining county.”

C. District union called for a multi-party negotiation that won workers’ wages in Shenzhen

In August 2020, a worker posted online saying that he was owed 1.67 million yuan for a project constructing a rain and sewage diversion system in the Bao’an district of Shenzhen. The worker, Ye Hong, stated that from October 2019 to June 2020, he and 18 others from Henan and Hunan provinces worked at the site and were never paid. The project general contractor was the state-owned Shanghai Communications Construction Company, which subcontracted to another entity with which the workers signed labour contracts. However, the workers’ payments were to come straight from the general contractor, and the workers were also to be supervised and managed by the general contractor.

With Ye acting as a worker representative, the workers compiled documentary evidence about this employment arrangement, including the project completion date and wages owed, based on a piece-rate system. The workers said that although a monthly wage system was agreed upon, the general contractor only paid part of the wages in December 2019. These wages were issued through bank cards, but since that time no additional wages were paid. After the completion of the project in the summer of 2020, the workers repeatedly went to the general contractor to settle the matter, to no avail. Soon, they could not reach the contractor at all.

CLB learned of this case and contacted the Bao’an district federation of trade unions, which contacted the companies involved and hosted a negotiation session the next day. At the end of August, the union invited the workers to join in the negotiations, which included the Shenzhen Bao’an water department for whom the work was conducted and the general contractor who the workers had not been able to reach.

The day after the meeting with workers, CLB contacted the district union and its rights protection department. The official leading the matter let us know that the trade union had mediated the negotiation and the general contractor would timely complete its inspection and acceptance of the project. Further, the general contractor promised to pay the wages within the next ten days. The union official told us that worker representative Ye had expressed his satisfaction with the result and assured us, “He will get the money quickly.”

D. The trade union’s identification of “eight major groups” for enhanced rights protection is a prime test case for union reform and accountability

The cases included in this report not only show the challenges encountered by workers in traditional sectors, but also reflect some new labour challenges faced by workers in new sectors and the modern economy. Specifically, the increase of workers in the service sector and rise of the platform and gig economy have created new situations for labour relations.

Although the longstanding problems of traditional sectors – like wages in arrears and illegal subcontracting in the construction industry, and work safety problems in hazardous industries - have still not been resolved, added to them are new facets such as online contracts, contract labour, precarious labour, etc. The large corporations in the gig economy have already taken advantage of the laws that have not caught up with our modern world, refusing to recognise the employment relationships of contract workers wearing their brand logos.

For example, a food delivery driver named Shao Xinjin was injured in 2019 while delivering food in Beijing. In the process of defending his right to compensation for the workplace injury, he discovered that his simple job involved five different companies. He wore the Ele.me uniform and used the Ele.me app to take orders, but his delivery site in Changping district, Beijing, was managed by Dias (Chongqing) Logistics Co. His salary was paid by Taichang (Chongqing) Catering Management Co., and the personal tax was paid by a Tianjin construction company and an outsourcing company in Shanghai. Ele.me, Dias, and Taichang all denied a labour relationship with Shao.

Ultimately, Shao travelled from Beijing to Chongqing in an attempt to defend his rights. First, he applied for arbitration in Changping district, Beijing, to confirm the labour relationship with Dias, and he won. Then, he brought the case against Dias in its place of registration in Chongqing to certify the application for work-related injury. Unfortunately, this claim was not successful, and Shao has not received his workplace injury insurance benefits.

Within this environment, the ACFTU has recognised emerging problems and has looked toward a solution. Since 2018, the ACFTU has identified what it calls the “eight major groups”: truck drivers, couriers, nursing staff, domestic workers, security guards, food delivery workers, retail workers, and real estate agents. The goal of the union’s work with these eight groups is to increase their union membership, identify emerging issues affecting their labour rights, and work to protect their interests.

In July 2021, the ACFTU along with eight ministries and commissions released standards on platform workers’ labour conditions. These “Guiding Opinions on Protecting Labour and Social Security Rights and Interests of Workers Engaged in New Forms of Employment” are high-level guidance urging for strengthened labour rights protections of workers engaged in precarious employment. This includes provisions that the union increase its membership of these groups, enhance rights protection for them, conduct negotiations, sign industry collective agreements, promote better industry standards, etc.

China’s national legislation is already clear that all workers are entitled to the protections of the Labour Law and other legislation, but in practice many workers fall through the cracks, through no fault of their own. The lack of a written labour contract, for example, is largely evidence of employers’ violations of the Labour Contract Law, and should not be considered a penalty or fault of the worker who can show other evidence of the employment relationship. In the gig economy, which relies on dispatched labour, informal working relationships, and other hazards of casual employment, these types of issues are all the more pressing for workers across the country who have reduced bargaining power in the face of giant corporations seeking more and more profit by exploiting legal loopholes that have yet to be filled.

In September 2021, the Beijing municipal federation of trade unions introduced guidelines designed to regulate and encourage unionisation for “gig” delivery drivers, workers and labourers in China’s capital city. The guidelines lay out ten major measures to improve union work in the gig economy. These include stationing union officials in the local community to gather and solve problems faced by workers, recruiting gig economy workers to join the union, utilising existing worker centres to contact workers, providing health checks and childcare services, and providing workers with skills training. The guidelines also state that the union will negotiate with companies on important issues such as pay, workplace policies, working hours, and other workers’ protections. In the meantime, the union will organize lawyers to provide legal advice and services for gig workers. The Beijing union’s guidelines are a model for how other unions can make moves to protect the rights of workers in the eight major groups.

In practice, however, the union has a long way to go. For example, how will the union attract food delivery workers to join? And how can the union establish a mechanism for collective bargaining between workers in the food delivery industry, platform companies and even industry associations to hold negotiations? How can the union help clarify the labour relationships of workers? How to solve the algorithmic management method that is meted out strictly with fines on drivers? How can the union establish systems to handle traffic accidents and medical insurance, and pensions and other social security systems that adapt to the occupational characteristics of the food delivery industry?

China’s trade union has identified its important role in this area, and CLB believes the eight major groups are an essential starting point to bring more workers into the union. As the union gains a better understanding of these workers’ needs, it can proactively craft industry regulations that protect workers’ rights. It is not enough for unions to step in and defend workers’ rights after a legal violation has occurred. In other words, the entire function of the union is rights protection work from the start, not just the small legal services offices that deal with violations of China’s laws.

The authorities are actively paying attention to workers in these new forms of employment, and we believe that trade unions are duty-bound to effectively safeguard workers’ rights in this field. There is a lot of room for improvement, and in the next section we provide detailed recommendations for China’s trade union to better protect all workers.

V. CLB Recommendations for the ACFTU to Effectively Defend Workers’ Rights and Interests

The tens of thousands of labour incidents we have collected in our mapping projects since 2011 provide insight to the types and frequency of incidents across the country. For example, our Strike Map data tracks the economic shift from manufacturing to the services sector, the labour effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and regional lockdowns, and consistently high frequency of rights violations in the construction sector and over wage arrears. Understanding these broad challenges assists CLB in identifying which of the individual cases we find in our maps are compelling cases to further investigate, both by contacting the workers involved and raising the cases with the local trade unions. Through these interactions and investigations into the union’s activities, we are able to provide concrete recommendations, below, to China’s official trade union that will address the widespread challenges we know that workers are facing.

1. Local unions must open wide their doors and receive workers seeking rights protection

"The worker is not a union member" should not be an excuse for unions to refuse representation. First of all, if union membership is to be a requirement, the union must conduct better outreach, which is in line with the focus on the eight major groups and increasing union membership. The internet and unions’ own online platforms can be a tool for promoting union membership, and workers should not face any costs or barriers to joining the union. Second, the requirement for a worker to be a union member to receive the union’s services does not track the reality for many workers who are unaware of the union’s existence, for companies with complicated corporate structures and systems of regional franchises, and for the many workers who request to join the union and are denied.

The territorial, hierarchical, and bureaucratic nature of the union should also not be an excuse to turn workers away. Rather, unions at various levels should coordinate with one another to provide assistance. Of course, the trade union has regional and administrative divisions, but these divisions should be utilised to better perform the trade union functions, not to pass off responsibility to the point that no entity accepts any responsibility at all. Instead, whenever workers walk through the union door for help, the union should be prepared to defend the workers’ rights.

2. Unions should look beyond legal aid for rights protection work and should reconsider the scope of the union’s abilities to help workers

Provision of legal aid is not synonymous with rights protection work. Article 22 of the Trade Union Law states that “where enterprises and institutions violate labour laws and regulations… the trade union shall represent the workers to negotiate with the enterprise or institution, and require the enterprise or institution to take measures. If the enterprise or institution refuses to make a correction, the trade union may request the local people’s government to deal with it according to the law.” Article 25 also states that “the trade union has the right to investigate the violation of the legitimate rights and interests of workers by enterprises and institutions.”

Therefore, unions should not decide whether to provide assistance to workers based on the odds of success in legal proceedings; rather, the union should intervene and play its essential role of representing workers’ rights and interests. CLB recommends that unions accomplish this by instituting collective bargaining mechanisms in the workplace. When an infringement of workers’ rights occurs, the union should raise the issue with management and negotiate on behalf of workers for just resolution. If employers are unwilling to negotiate, at that point the union can engage in the process of going through mediation, arbitration, and perhaps on to the civil courts, representing the workers the whole way. Even if workers do not ultimately succeed in the legal proceedings, the fight for justice is meaningful.

3. The union’s assessment of its own rights protection work should focus on qualitative indicators

Since the announcement of trade union reform initiatives, unions have coped with this new pressure by aggregating statistics as proof of their achievements. For example, the union may cite the number of legal consultations conducted, total number of rights protection cases taken on, and amount of money recovered on workers’ behalf. This data is important, but it cannot be used as a substitute for indicators of the union’s effectiveness in protecting workers’ rights. For example, the amount of recovered losses is likely correlated with results of labour inspection work, not negotiations with employers or successful outcomes of legal decisions. In addition, the focus on quantitative indicators leads the union to only accept cases in which victory for the worker is likely to result, leaving workers who need help the most to fend for themselves. We suggest that the union focus instead on results of case-based work.

4. Rights protection should be an opportunity to deepen all aspects of ACFTU reform

Rights protection work should be integrated with the union’s organization and negotiation work, rather than be isolated as its own department. By mainstreaming rights protection work, unions can enter workplaces, build the trust of workers, and identify and assist workers in their needs before accidents or labour disputes arise or escalate. This approach to rights protection is in line with the union’s other goals, such as building up union membership, achieving collective contracts, and raising the labour standards within industries.

In fact, Article 3 of the Trade Union Law states that “trade unions adapt to the development and changes in the organizational form of enterprises, workforce structure, labour relations, employment forms, etc., and protect the rights of workers to participate in and organize trade unions in accordance with the law.” Trade unions at all levels should understand the Trade Union Law and the union’s role in protecting labour rights across the board.

5. Rights protection work should inform labour policy formulation

We recognize that many of the trade union officials we speak to have rich first-hand experience with workers’ rights issues. The union can utilise this experience and the realities they observe workers facing every day to promote how the law can better protect workers, starting from the interests of workers rather than needs of the economy, enterprises or other interests. This can happen through labour policy formulation. The trade union can offer advice on new legislation and the drafting of amendments, and otherwise provide policy recommendations to the various levels of the state structure. Not only have recent national pieces of legislation been amended, such as the 2021 revisions to the Work Safety Law, but also provincial, municipal, and local governments are constantly enacting regulations that affect workers’ rights.

By considering rights protection primarily as provision of legal aid, the trade union has become stuck in the perspective of current legislation and viewing situations that fall outside that framework as hopeless cases. However, it is precisely these administrative, legislative, and judicial gaps that are useful for the trade union to explore. Further, many basic rights already have strong protections in the law, such as wages in arrears and uncompensated workplace injuries, yet these are the most frequent labour disputes that continue on a massive scale. The trade union can consider taking initiative to offer solutions to eliminate once and for all these constant violations that have continued despite their clear illegality.

6. The ACFTU should move beyond its role as a “mass organization” of the Party

Xi Jinping’s demand for trade union reform involves eliminating the union’s bureaucratic nature. We believe this starts with abandoning political slogans and empty displays of loyalty that are not backed by concrete actions to represent workers’ interests. In fact, one impediment to its own work is that in negotiations between workers and management, the union is proud of its “neutral” role in resolving disputes. However, as a mass organization of the working class, its role is to stand on workers’ side in the path toward justice.

VI. Conclusion: The ACFTU Must Broaden Its Scope of Rights Protection Work

The role of the trade union is to defend workers’ rights and interests. However, we have found that the rights protection function of the union is limited to litigating violations of rights after they occur. By broadening the scope of rights protection and integrating this role throughout the union structure, the union will be better situated to fulfil its mandate of reform and represent China’s workers.

The best way for the union to help workers - whether they are facing wage arrears, a workplace injury, or unpaid social security - would be to anticipate these problems in advance and resolve the issues before legal channels are necessary. For example, a collective bargaining mechanism at the factory level could be a platform to regularly discuss the needs of workers, and labour disputes could be resolved without strikes, protests, and desperate social media posts from workers facing no other options. As for workplace safety, listening to the concerns of frontline workers will go a long way in protecting workers and preventing accidents from occurring.

As the only lawful representative of China’s millions of workers, the ACFTU must understand the power of its members. The union should utilise workers as a resource by going into work sites to understand their workplace conditions, proactively contacting workers in need, representing workers through negotiations, and helping workers navigate the burdensome legal channels to claim their rights when other avenues have failed. The union can start by reaching out to workers and making them feel at home with the union, ensuring workers that where their rights have been infringed, the trade union will stand up and speak out.