In India, gig workers challenge platforms online in war of words

30 September 2021Kunal Purohit* reports from Mumbai on how gig workers are exposing exploitative practices on social media to reach an important ally: consumers.

Social media users in India have long chuckled at creative advertisements from the country’s two major food delivery platforms, Swiggy and Zomato*. The messages range from asking citizens to stay at home during India’s ferocious coronavirus outbreak, to sassy tweets stoking patriotism, to tongue-in-cheek responses to rivals.

These corporations’ social media presence has won hearts and clicks. But this era of positive public relations is changing.

Their carefully curated online presence is now being challenged by gig workers employed by these same platforms who are also taking to social media to highlight their abysmal working conditions and precarious jobs. Worker groups are encouraging gig workers to open social media accounts, often anonymously, and share their everyday experiences of struggles and hardships they face while delivering food.

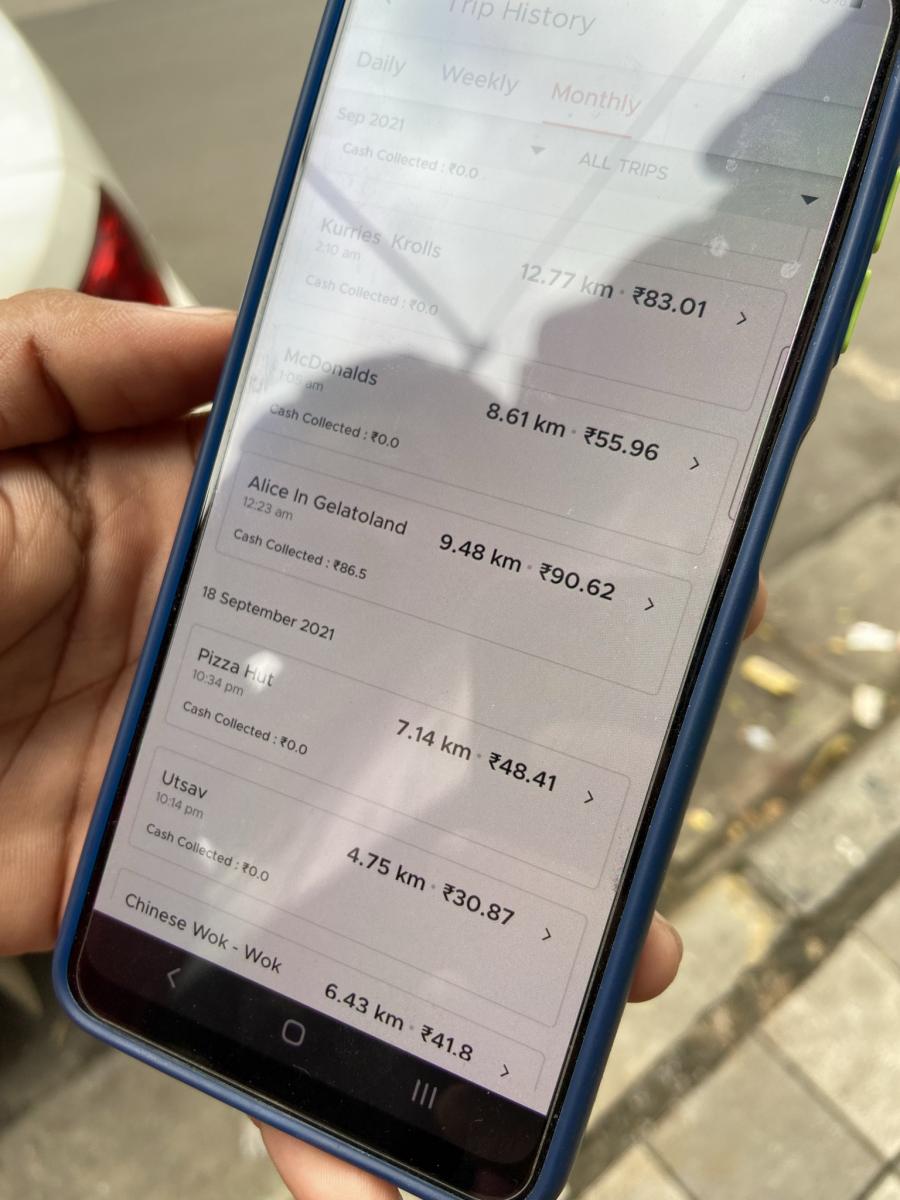

From uploading screenshots of their meagre earnings to calling out platforms for exploitative systems, these workers are increasingly drawing consumers’ attention to their woes. In doing so, these workers are sensitising the public about the struggles they face in delivering food to consumers’ doorsteps and - in the process - forging solidarity.

This consumer-worker solidarity is pushing companies to take steps to address worker issues.

Zomato delivery workers wait to collect food orders in suburban Mumbai. Photo by Kunal Purohit.

Recently, Zomato had to clarify that it was “intently listening to all the chatter about gig workers and all the problems associated with this part of the economy.” Zomato even launched a new ad campaign to “humanise” delivery agents working for it, a move that is seen as a response to the criticism it has garnered on social media over the poor working conditions it has created for these workers.

Such statements, though, are in stark contrast to the actual treatment of workers by these platforms in recent times.

Amid the economic devastation wrought by the pandemic in India - with the economy shrinking by 7.7% - the online food delivery business grew. The health risks associated with dining out and restaurants across the country operating under pandemic-induced restrictions has led to food deliveries soaring. Swiggy went from 30 million orders a month in January 2019 to nearly 45 million orders a month in 2021, while Zomato said it had delivered 239 million orders between April 2020 and March 2021.

During this same period, both companies received huge financial boosts from investors. In July 2021, Swiggy raised $1.25 billion, increasing the company’s worth to $5.5 billion. In the same month, Zomato made its market debut and was valued at over $12 billion.

But workers said they didn’t get any share.

Shaik Salauddin is the national general secretary of the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT). “While these companies grow, they are slashing the rates of delivery workers and forcing them to increase their working hours,” Salauddin said. “We want every investor in these companies to learn the ground realities of the way these companies treat their workers, their backbone.”

Rajprakash Tiwari*, a 43-year-old Swiggy driver, agreed. At the junction of a busy crossroad in the Mumbai suburb of Andheri, Tiwari wore a black t-shirt with Swiggy’s orange logo. He said his wages have decreased since the start of the pandemic.

“After the lockdown last year, when food deliveries resumed, we realised that the fixed charge we used to earn on each order was unilaterally reduced from Rs 35 ($0.47) to Rs 20 ($0.27),” Tiwari said. This has had cascading effects on workers’ earnings, because agents get an “incentive” amount from the platforms when they earn a certain amount of money each day. The incentive amount varies from agent to agent, according to an algorithm, in order to lure workers into longer hours.

“But, after they reduced our rates, it is now taking us double the number of orders to earn the same amount. This way, they can rob us of our incentives without officially denying it,” Tiwari added.

Swiggy delivery agents rest between orders behind a restaurant in suburban Mumbai. The city lacks adequate shelter and amenities for gig workers. Photo by Kunal Purohit.

Such stories are common among workers. Sebastian D’souza*, a 24-year-old in Mumbai who has worked for three years as a delivery agent for both these companies, quit in December 2020, despite his family’s precarious financial position. His father died of Covid-19 that year, and the family incurred a heavy debt for his hospital bills. Yet D’souza quit after he got into traffic accidents on three occasions while delivering food parcels, and he was penalised each time.

“I tried to tell them that I had an accident, but the company asked me to pay the bill amount as penalty, instead,” said D’souza. He now delivers packages for e-commerce companies and insists the working conditions are “much better.”

It is practices like these that worker groups are now exposing on social media, one screenshot at a time.

These worker groups have highlighted a wide range of issues: the grave injuries that workers suffer while carrying out deliveries, the inconsistencies in insurance that companies offer, the penalties that workers incur when consumers complain about restaurants’ poor packaging, and even penalties for following customers’ instructions.

Workers have also turned their attention to the attitudes of restaurants towards delivery agents, from the lack of basic facilities for agents waiting for orders, to restaurants adopting discriminatory policies.

Salauddin said that the social media guerrilla tactics are a part of a calculated strategy that worker groups like IFAT have had to adopt. He explained that as these companies increase their advertising budgets, mainstream media organisations have appeared to tone down their coverage of the workers’ struggle.

Last September, IFAT spearheaded a 27-day strike of Swiggy workers in the southern city of Hyderabad. There have also been similar strikes in 2019 - in Mumbai, Bengaluru and Delhi - but Salauddin said they have hardly helped. The rise of third-party companies has supplied a continuous stream of new workers to these platforms.

“Instead, when we write on social media, we connect directly with our users, so that they know, first-hand, what our struggles are,” Salauddin said.

IFAT encourages and teaches workers to use social media more effectively, while remaining anonymous. “It is tricky since [agents] can be sacked by these platforms if their identity is revealed. So, we tell them to upload screenshots and evidence of the poor working conditions these companies have created,” he said.

On Twitter, for instance, a clutch of social media accounts have mushroomed. Accounts like @DeliveryBhoy, @SwiggyDEHyd, and @ZomatoPartners share struggles of fellow gig workers and inspire many others to join in.

These methods don’t always lead to satisfactory resolution in each case.

Swapnil Joshi*, 27, is a Mumbai-based delivery agent with Swiggy. Even though Joshi has only a handful of followers on Twitter, he is not shy about challenging his employer.

Last month, Joshi received an order to deliver a box of sweets from a shop that was over 5 kilometres away from his current location, so he kick-started his motorbike and rushed there. Only 15 minutes later, he was at the shop waiting for the order to be packed. But then, the order was suddenly cancelled without any explanation. Joshi was paid Rs 10 ($0.14), which he said would not even compensate for his fuel.

Joshi posted his ordeal on Twitter, forcing Swiggy to respond. The company only asked him to fill out a form, and Joshi said he was never paid for his time.

A food delivery agent's cell phone screen displays recent orders and amounts earned. Photo by Kunal Purohit.

IFAT’s Salauddin agreed that raising the issues on social media does not always result in the problems being resolved, but the point is that workers are using their voices. “Izzat ka sawaal ban raha hai. It is becoming a matter of our pride,” he said, “which is why we want to run our social movement through these social media posts.”

IFAT has filed a plea with India’s Supreme Court, asking it to direct all four major gig companies - Zomato, Swiggy, Uber and Ola - to implement social security schemes for its workers and urged the court to categorise the failure to do so as a violation of workers’ fundamental rights. The plea also asked the court to ensure that gig agents are recognised as “unorganised” workers so that they can benefit from government schemes. The plea is yet to be heard in court.

IFAT said that while it was encouraging workers across the country to organise into local, region-based collectives, it prefers advocacy and litigation over unionising. “In all these years, we have realised that these big companies don’t care about unions and are unwilling to engage with unions,” Salauddin said. “This is because there are no specific laws, currently, that force these companies to provide for gig workers. Once such laws are in place, we can push these companies to implement them through worker unions.”

Balaji Parthasarathy is a professor at the International Institute of Information Technology in Bangalore and the principal investigator of the Fairwork project in India. Fairwork India publishes annual reports comparing work practices in companies within the platform economy. Parthasarathy says it is “more than about time” that workers’ conditions are highlighted publicly, saying that it serves a dual purpose.

“Consumers must know what they are encouraging,” Parthasarathy said. “I am hopeful that it will also get companies to react and bring about changes in the working conditions.”

The 2020 annual report by Fairwork India found Zomato and Swiggy at the bottom of the ratings in the five principles on which it evaluated different platform companies: fair pay, working conditions, contracts, management, and representation of workers.

Parthasarathy said workers’ social media posts are also creating solidarity among workers, especially in the face of “sporadic” efforts to unionise them. “Unions in the sector are relatively rare because these are all atomised workplaces, with each worker to his own. They don’t have fixed workplaces and hence, there is no engagement with other workers, and no chance to collectivise,” he said.

In addition, as the Fairwork India report points out, companies like Zomato warn workers against strikes or any “acts such as creating ruckus/activity against Zomato,” adding that such activities could lead to termination.

“Workers are also scared of striking work now, because there is a danger that employees of these third-party companies can swoop in and replace them," said Mounika Neerukonda, a researcher with the Fairwork India project.

Parthasarathy said that social media provides a different way for workers to be heard. “Now, social media is providing them a means to articulate themselves before the public and highlight their struggles,” he said.

In light of increased public awareness and changing perceptions, some companies have launched ad campaigns in response, highlighting the contributions of delivery personnel as “heroes.” Such attempts have been met with even more criticism.

Recently, a comedian who filmed a commercial for Zomato in which he became a delivery agent for a day was criticised for whitewashing the working conditions of these workers, and he was forced to apologise for appearing in the ad. Another series of commercials by Zomato, featuring food deliveries made to popular Hindi film stars, was met with flak, forcing the company to issue a response.

What has been constant in these episodes is the involvement of consumers in joining ranks with workers in taking on companies.

Companies might be underestimating the power that this worker-consumer solidarity has in lobbying for better work conditions, said Neerukonda. “Over the years, there has been a shift in surveillance and power towards the consumer, with their ratings and their feedback determining everything from the workers’ earnings to their working conditions,” she said.

“So far, very few were aware of what happened when they rated a food delivery at 2/5. We are now seeing a slow rise in awareness about consumers about their role in the process,” she added.

* Kunal Purohit is an independent journalist based out of Mumbai and focuses on issues of development, social justice and politics.

* Swiggy and Zomato did not respond to requests for comment.

* Names have been changed at the request of the interviewees.