Workplace discrimination

07 July 2020For the Chinese version of this article please see 工作场所中的歧视 on our Chinese website.

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China stresses that all citizens are equal and that ethnic minorities, people with religious beliefs, and women are not to be discriminated against in any aspect of civil life, including employment. China has, in addition, numerous laws and government policies designed to promote employment equality. Yet, employment discrimination is pervasive and still widely tolerated, practiced by both private employers and government institutions. Laws and regulations aimed at eliminating employment discrimination are hampered by technical shortcomings, ineffective enforcement and conflicting legislation and government policies that appear to promote, rather than discourage, the continuation of discriminatory practices.

This introduction will provide an overview of the main forms of employment discrimination in China (those based on gender, age, household registration, health status and disability, ethnicity, and sexuality) an analysis of the current legal protections available to workers and an assessment of the legal and policy reforms that are still needed to adequately protect workers from employment discrimination.

Jump to individual sections:

- Gender discrimination

- Discrimination based on age

- Discrimination based on the household registration system

- Discrimination against workers with physical and mental disabilities

- Discrimination against workers with HBV and HIV

- Ethnic and religious discrimination

- Lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgender discrimination

- Laws and regulations related to employment discrimination

- Deficiencies of the current laws

- Conclusion and recommendations

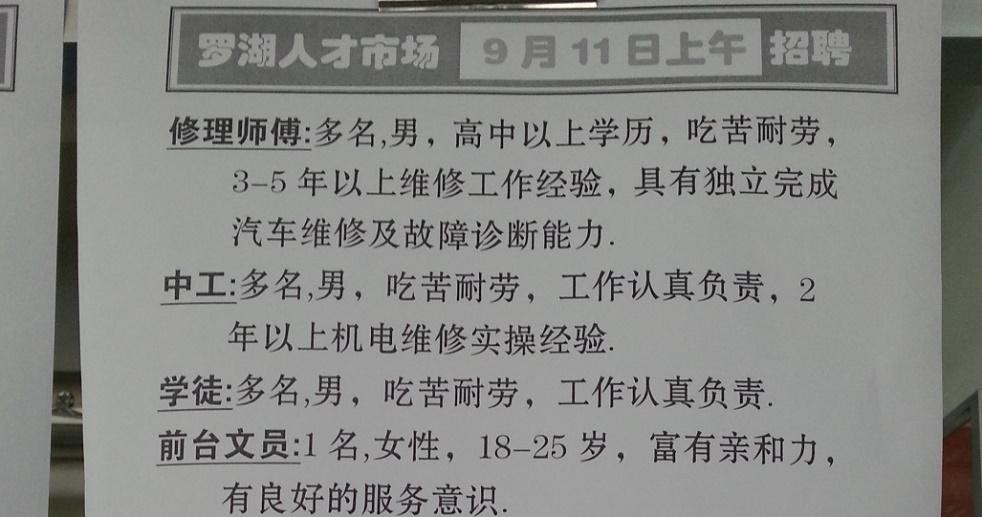

Job seekers examine their options at the Longhua Recruitment Centre in suburban Shenzhen.

In February 2019, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) published a Manual for Promoting Gender Equality at Work. It was an important contribution to the long-running struggle of women for equality in the workplace that argued for greater employer accountability and a stronger role for the trade union in combatting discrimination. However, the manual also perfectly illustrated just how pervasive and serious the issue of gender discrimination currently is in China. It pointed out that gender discrimination is not simply confined to the recruitment process (where it is often quite blatant) but exists in all areas of employment from renumeration and career advancement, training, work-life balance, and working conditions, and in particular with regard to workplace violence and sexual harassment.

While there is growing support for gender equality from institutions such as the ACFTU and the courts, there is also push back from employers, advocates of traditional, deeply entrenched, patriarchal values, and to some extent the Chinese government, which is increasingly concerned over the country’s low birth-rate and is stressing the need for women to focus on raising a family rather than their own career advancement.

Workplace discrimination actually begins well before women even enter the workforce. The practice of gender-based quotas and discriminatory enrolment policies in higher education is widespread, often resulting in women having to score higher marks than men in entrance examinations for certain majors. The Education Ministry defends this practice at military and police training academies on the grounds of “national interests” but the explanations given by university administrators who create gender-based quotas often amount to nothing more than paternalistic judgments about the kind of roles women are best suited to.

Once women start to seek employment, they immediately encounter even more formidable barriers. Despite legal prohibitions on gender discrimination in hiring, recruitment advertisements often overly state that certain jobs are for men, while other (usually less prestigious and lower paid) jobs are reserved for women. A survey by Human Rights Watch (HRW) of more than 36,000 job advertisements posted on Chinese recruitment and company websites and on social media platforms between 2013 and 2018 confirmed the prevalence of “men only” ads in both the public and private sector. In 2018, for example, 19 percent of all the vacancies posted on the Chinese national civil service job list specified “men only,” “men preferred,” or “suitable for men.” In contrast, only one ad specified a preference for women.

In general, men are preferred for physically demanding jobs (there are, in fact, specific legal provisions that “protect” women from employment in logging, underground mining, setting up power lines or scaffolding etc.), as well as white-collar managerial and civil service positions and work related to engineering and technology. Women, on the other hand, are preferred primarily for jobs in service industries, sales and clerical positions. Moreover, positions that require interaction with the public, such as receptionists and airline cabin crew, usually have maximum age, minimum height and other physical appearance requirements. One typical recruitment ad for Yintong Auto Repairs, seen at a jobs fair in Shenzhen in September 2015, stated that the company required:

-

Male mechanics: high-school education, hard workers with three to five years’ experience and the ability to maintain vehicles and diagnose faults.

-

Male labourers: hard workers with more than two years’ hands-on mechanical experience.

-

A female receptionist: 18-25-years-old, congenial, with a good sense of service.

Even without overtly stating any appearance requirements, the common practice of requiring photographs in job applications allows employers to easily discriminate against individuals based on looks. Moreover, the HRW report reveals that some major companies like Alibaba actually ran recruitment ads boasting of “beautiful girls” or “goddesses” working for the company as a means of attracting male applicants. Alibaba later promised to address discrimination in its job ads but less high-profile companies may be slower to change their ways.

For many years now, women have been fighting back and suing employers for discrimination. In 2013, Cao Ju filed what is believed to be China’s first gender discrimination lawsuit. Cao took the Juren Academy in Beijing to court after it refused to consider her for a position as an administrative assistant. The post had been advertised as for men-only. Cao accepted 30,000 yuan in damages and a formal apology from the Academy after a year-long legal struggle. This high-profile case, dubbed one of the ten most important public interest cases of 2013, encouraged more women to protest discriminatory recruitment practices. The following year, a Hangzhou court ruled that a well-known educational institute in the city had violated a job applicant’s right to equal employment and had committed employment discrimination by restricting job applications to men only. The West Lake District Court further ruled that the respondent, the New Oriental Cooking School should pay the plaintiff 2,000 yuan in damages for mental distress. In November 2015, a Beijing court ruled that the city’s postal service had discriminated against a job applicant simply because she was a woman. The plaintiff, 25-year-old Ma Hu, had sought 57,570 yuan in compensation and a formal apology from the Beijing Postal Service. However, the court rejected her demand for an apology and only awarded her 2,000 yuan, the same amount as in the Hangzhou case. Despite these court judgements’ acknowledgement of discrimination, the token fines imposed are unlikely to be a major deterrent to other discriminating employers.

Even without overtly discriminatory provisions in their recruitment advertisements, employers can still seek to impose discriminatory conditions on female employees. Employers often ask prospective female workers about their family plans, out of concern that female workers will leave their jobs after marriage. Employers sometimes require women to undergo pregnancy tests or adhere to stringent conditions regarding plans for marriage and pregnancy. Many employers find ways to coerce pregnant workers into resigning by requiring them to work unreasonable hours or giving them increased workloads. Applications for maternity leave were often turned down leaving many women no option but to resign in order to look after their new-born baby. And this situation is likely to deteriorate further as China relaxes family planning rules and encourages women to have more children.

Some women have successfully sued for illegal dismissal while pregnant. For example, a Beijing shopping mall counter manager, Yin Jing, was awarded 62,237 yuan in compensation by a Beijing appeals court on 5 November 2015 after she had been illegally fired while pregnant. However, for most women, especially low-paid factory workers, going to court or even labour arbitration is simply not an option because they cannot afford the time and money to do so.

As in just about every other country, many women in China earn significantly less than men, often in exactly the same position. According to a 2018 survey of relatively well-paid white collar employees by an online recruitment platform, women earned on average 6,497 yuan a month, or just 78 percent of the average wage for men. The survey noted that it is much more difficult for women to be promoted through the ranks of management, particularly in the fields of engineering and manufacturing, where men occupy 95 percent of senior management positions. Given the almost unbreakable glass ceiling that exists in many workplaces, there appears to be a growing sentiment in China, among women as well as men, that the best way for women to get ahead is to marry well rather than pursue a career. One survey showed that, while only 37.7 percent of women in 2000 thought it was better to marry well than forge a career, that proportion had risen to 48 percent in 2010. However, the picture is complicated. Many younger women are also putting off marriage entirely to focus on their careers. In a survey of white-collar workers in 2018, for example, only 49 percent of women thought that marriage was a necessity.

Achieving a reasonable work life balance is a constant struggle for married women workers with families, particular in the technology sector, which is notorious for long working hours and punishing schedules. Women on average spend twice as much time doing housework and looking after their families as men, according to one survey published in March 2019, however they are still expected to work just as hard as their male colleagues. Many married women with children are forced to quit the industry because of the heavy workload and uncompromising attitude of management. Moreover, women are usually the last to be hired and the first to be fired when there is an economic downturn or company profits fall.

Sexual harassment and intimidation at work is a serious and widespread problem in China, as evidenced by the outpouring of complaints during the #MeToo movement when women from all over the country came forward with charges against powerful and influential men, mainly in universities, civil and religious organizations, and the media. There were at least 36 major #MeToo cases that came to light in the first ten months of 2018 alone. Despite online censorship, the movement has proved unstoppable, partly through the creative use of symbols and homonyms for #MeToo such as 米兔 (rice bunny) but mainly because of the sheer volume of complaints that had been building up over the decades.

Back in 2013, a survey of factory workers in Guangzhou revealed that up to 70 percent of female employees had been victims of sexual harassment. However, most victims at that time were reluctant to file a formal complaint or take the matter to court. About 43 percent of the respondents in the survey said they suffered in silence, while 47 percent said they dealt with the harassment directly.

There were however a few sexual harassment lawsuits prior to #MeToo. In 2009, for example, a 28-year-old office worker, Ms. A, was fired after complaining about blatant sexual harassment by her Japanese boss, which was even caught on camera during an office party. The court ordered the defendant to make a formal apology and pay Ms. A 3,000 yuan in compensation for the mental anguish caused by the incident.

Age discrimination often goes hand in hand with gender discrimination, with age limits on female applicants being particularly commonplace. However, while gender discrimination is still a major issue, age discrimination has become slightly less problematic over the last decade due to China’s rapidly aging workforce.

During the boom decades of the 1990s and 2000s, factory owners and other employers could rely on an ample supply of young workers from the countryside to fill their job vacancies. Employers would often restrict applicants to those under 30 or even 25-years-old in the belief that younger employees would be cheaper, more productive and more compliant than middle-aged workers. However, as the economy grew and fewer new workers entered the workforce, employers were forced to cast a wider net and recruit older workers. The world’s largest electronics manufacturer Foxconn, for example, now only specifies that job-seekers at its Shenzhen plant have to be of “working age - as stipulated by national laws and regulations.”

Age discrimination is still an issue however in the service industry and particularly in sought-after professional positions. In September 2015, the online shopping platform Oupinwu.com (欧品屋) was offering a monthly salary of between 8,000 yuan and 15,000 yuan per month with full benefits for new managerial staff but restricted the available positions to applicants aged between 23 and 30-years-old who are both “optimistic and articulate.”

While there are more job opportunities for older workers in China compared with a decade ago, many of the jobs on offer are still poorly-paid, insecure and occasionally hazardous. One growth area for older workers is the construction industry, where the average age of workers is probably more than 40-years-old. This sector is however notorious for its lack of formal employment contracts, systematic wage arrears and dangerous working conditions. About 35 percent of all the incidents recorded on CLB’s Work Accident Map in 2015 were in the construction sector, usually related to structural collapse, mechanical failure or falling from a height.

Discrimination based on the household registration system

China’s household registration (Hukou 户口) system was formally introduced by the Communist government in 1958 and was designed to facilitate three main programs: government welfare and resource distribution, internal migration control, and criminal surveillance. Each town and city issued its own domestic passport or hukou, which gave residents access to social welfare services in that jurisdiction but not others. Individuals were broadly categorised as a "rural" or "urban" based on their place of residence. Moreover, the hukou was hereditary so children whose parents held a rural hukou would also have a rural hukou no matter where they are actually born.

The hukou system was supposed to ensure that China’s rural population stayed in the countryside and provide the food and other resources that urban residents needed. However, as the economic reforms of the 1980s gained pace hundreds of millions of young men and women from the countryside poured into the factories and construction sites of China’s coastal boom towns. The migrant worker population has grown steadily since then, reaching 291 million in 2019.

Although restrictions on migrant worker access to social services have been relaxed in many cities, there are still substantial barriers to housing, healthcare and education for their children, particularly in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. These restrictions give migrant workers, who generally have a much lower income than urban workers, an additional financial burden in terms of healthcare and school fees that they very often cannot afford.

Migrant workers in Chengdu, provincial capital of Sichuan

Hukou discrimination also affects urban professionals from other cities. A survey of employers of college graduates in 2010, for example, found that nearly 60 percent of them set specific hukou requirements for prospective employees. Some job seekers have challenged these restrictions in the courts but apart from one notable case in 2013 in which a graduate from Anhui sued the Nanjing Municipal Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security for discrimination, the courts have been reluctant to take on such cases because they are seen as threatening the interests of the municipal authorities. Court officials, including judges are paid by the local government and will inevitably seek to avoid any cases that might create a conflict of interest.

Despite numerous pledges and proposals by central government officials to reform the hukou system and make life easier for migrant workers, it is individual cities that will determine the pace of hukou reform, based on their own needs and their ability to accommodate new arrivals. For more details see our in-depth article on migrant workers and their children.

Discrimination against workers with physical and mental disabilities

Workers with physical disabilities, such as those with limited sight, hearing and mobility face routine and widespread discrimination in China. As Wang Zhijiang of the China Disabled Persons' Federation explained “in reality, there are no disabled people who cannot work, just a lack of jobs that are suitable for disabled people.” The refusal or reluctance of employers to create an accessible and open work environment means that for people with disabilities finding any form of employment can be extremely challenging.

The issue was highlighted in April 2019 when a visually impaired man was refused a teaching post at the Nanjing School for the Blind allegedly because his eyesight was not good enough. Zheng Rongquan, a graduate of Wenzhou University, got top marks in the application test but was never offered a job, prompting vigorous discussion online. Zheng himself noted in a WeChat post that he had sufficient vision to see people walk in and out of a classroom. He added that his experience at both blind and regular schools proved he was capable of teaching at a school for the blind. “Since I entered regular college, I've been trying to use my actions to help able-bodied people understand the visually impaired,” he wrote. “If I can't become a teacher and am forced back to do massages … then I won't have opportunities to show to the world how we really live and what kind of abilities we have,” he added.

A 2010 report found that only 34 percent of urban and 49 percent of rural disabled individuals with the ability to self-care were actually employed. Moreover, those disabled persons that do manage to find employment are often marginalized in low-paying positions that able-bodied employees are reluctant to take on, such as blind persons working as masseurs. Long-term unemployment for people with disabilities is serious problem in China, with millions of unemployed disabled persons living in poverty.

Pang Jinpeng (above) has not been able to work since 1977 when, aged just 19, he was hit by a tanker at the state-owned coal mine he was employed at. He was paralyzed from the neck down and has spent most of his adult life confined to his home.

In an attempt to improve employment opportunities for disabled workers, the State Council introduced the Regulations on the Employment of People with Disabilities in 2007, which mandated that all enterprises reserve at least 1.5 percent of their workforce positions for disabled workers, or otherwise pay into an employment guarantee fund for the disabled. However, it seems this regulation is widely ignored, even by local government departments. A survey of government departments in 30 Chinese cities by the anti-discrimination pressure group Yirenping found that the highest percentage of disabled employees in any government department was just 0.39 percent, with some departments having as low a percentage as 0.02 percent. Nor is it certain that money going into employment guarantee funds is being used for the primary purpose of providing employment services to the unemployed and disabled. Reports indicate that corruption and misuse of funds are rampant. An audit of the funds used in Zhejiang found that only 13.7 percent of the funds were actually used for professional training and employment services for the disabled; in one Hubei county 80 percent of funds were used to pay staff benefits and administrative expenditures.

Some small improvements have been made in disabled access to employment recently but only because disabled activists have challenged the system in the courts. The Anhui provincial government, for example, provided electronic versions of the civil service examination paper and relevant accessible software at the request of visually-impaired candidates, after disability rights activist Xuan Hai filed a lawsuit against the local government in 2012.

For workers with mental disabilities and those suffering from mental illness, finding and keeping a job can be highly problematic. White collar professionals with mental illnesses, for example, are often dismissed for failing to meet work targets etc. In June 2008, an engineer at IBM in Shanghai was awarded more than 57,000 yuan in compensation by a labour dispute arbitration committee after he was dismissed for “misconduct” after being diagnosed as bi-polar and attempting suicide. However, it is rare for employees to successfully sue their employer for mental illness discrimination and in most cases employees have little recourse and limited sympathy or understanding from other employees and members of the public.

People with severe learning disabilities are extremely vulnerable and at risk of exploitation by unscrupulous business owners. Probably the most notorious example of this kind of exploitation was the “black kilns” scandal of 2007 in which hundreds of children and many adults with mental disabilities were forced to work in brick kilns in the central provinces of Shanxi and Henan. But similar cases have been reported in Chinese media on a regular basis since. Indeed many such cases only come to light when they were exposed by investigative journalists. In one case, a reporter revealed that around a dozen workers have been held in a state of indentured servitude in a building materials factory in Xinjiang for around three years, working long hours in appalling conditions for no pay. They were beaten if they tried to escape and given the same food as the bosses’ dogs. The workers, eight of whom reportedly had mental disabilities, had been sold to the factory by an organization called the “Beggars Adoption Agency” of Qu county in Sichuan. The agreement specified that the factory should pay the agency a one-off fee of 9,000 yuan, plus 300 yuan per month per worker and compensate the agency 1,000 yuan for each worker “lost.” The workers themselves did not receive any money.

Discrimination against workers with HBV and HIV

There are an estimated 120 million people in China living with HBV, the virus that causes Hepatitis B; nearly ten percent of the country’s entire population. Like HIV (the virus that causes AIDS), HBV can only be spread through the direct exchange of bodily fluids: Daily contact poses no risk to others. However, it is widely believed in China that Hepatitis B is a contagious disease that can be spread through casual contact at school or in the workplace.

People with HBV were systematically excluded from public and private sector employment until the mid-2000s when anti-discrimination activists started filing lawsuits against employers, including local governments. The anti-discrimination group Yirenping was particularly successful in not only winning lawsuits but in publicising the cases and putting pressure on the government to change the law. Restrictions have now been lifted and fines introduced for employers who illegally test prospective employees for HBV. Despite these improvements, in 2011 Yirenping found in a survey of 180 state-owned enterprises, that 61 percent still conducted screening for HBV and 35 percent stated that they would reject job candidates with HBV. In fact, employment discrimination against people with HBV is still so common that many candidates have resorted to cheating their way through medical exams. There is a thriving black market for cheating services or so-called “gunslingers” (体检枪手) who can charge substantial sums for taking pre-employment medical tests for candidates with HBV. See Yirenping’s in-depth research report on HBV discrimination, published in 2010, for more details.

People with HIV face similar if not worse discrimination, again stemming from fear and a lack of basic medical knowledge. A Peking University professor argued in 2010, for example, that HIV positive individuals should not be teachers because “the immunity of students under 18 may not be strong enough to resist the virus.” And a 2007 study showed that 48.8 percent of the Chinese population and 65 percent of employers surveyed believed that people with HIV did not deserve equal employment rights. Many provincial governments still ban people with HIV from working as teachers. However, in a landmark case in 2013 that is believed to be China’s first successful HIV discrimination lawsuit, a teacher sued the Jiangxi Education Bureau when it refused him a job because he tested HIV-positive in his pre-placement medical. The plaintiff eventually agreed to withdraw the lawsuit in return for a 45,000 yuan settlement.

Ethnic and religious discrimination

Ethnic tensions have persisted since the founding of the Peoples Republic (PRC) in 1949 and have been exacerbated in the last three decades by the steady migration of ethnic Han Chinese into Uighur and Tibetan regions of China in particular. In an attempt to ease ethnic tensions, the Chinese government has introduced a range of “positive discrimination” measures for ethnic minorities including the allocation of development funds to minority areas, the relaxation of family planning rules and easier university entrance exams for minorities. These measures have however led to resentment among the Han majority and have done little to ease employment discrimination against minorities. In a 2011 study of 10,796 advertised job positions, researchers found significant discrimination against job applicants with ethnically distinct names. Only about half of the companies contacted had treated applicants equally regardless of ethnicity. Even in government departments, discrimination continues to be tolerated. Local governments sometimes specify ethnic requirements for departmental positions. There are also restrictions on religious practices amongst civil servants and government employees, one of the more egregious being forbidding civil servants, teachers etc. in Xinjiang from fasting during Ramadan.

Ethnic and religious minorities routinely face discrimination in the service sector, especially in low-level retail and restaurant positions where employers prefer to hire staff who appear more “familiar” and less “threatening” to Han customers. Very often minorities are effectively restricted to working within their own communities or in ethnically- themed restaurants.

In manufacturing, factories sometimes hire groups of ethnic minority workers en masse in order to make up for labour shortages in their local area. However, ethnic tensions between these workers and local Hans, who often believe the minority workers are getting a better deal, can lead to violent outbursts. Perhaps the best-known example of such violence occurred in June 2009 in a toy factory in Shaoguan, northern Guangdong (photo below). After rumours started to circulate that a Uyghur worker had raped a Han woman, a mass brawl erupted among thousands of workers, leaving two dead. In response, the employer removed all Uyghur workers to another factory in a small industrial park, 15 kilometres outside the city.

Lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgender discrimination

Homosexuality was officially still a crime up to 1997 and was only removed from China’s official list of mental disorders in 2001. Although there is still a stigma and considerable misunderstanding associated with homosexuality in China, most employers operate what could best be described as a “don’t ask don’t tell” policy. If their sexuality is made public however, homosexual employees can face reprisals. One survey found that about a quarter of the respondents whose sexuality had been revealed at their workplace had been fired or forced to resign as a result.

It is important to note that there are no specific laws or regulations that protect workers against discrimination on the basis of their sexuality, and so far there have only been a few isolated cases where employees have taken legal action over their dismissal.

In what is believed to be China’s first ever sexual-orientation discrimination lawsuit, a former employee, Mr He, sued a Shenzhen interior design company after he was allegedly sacked for being gay. The Nanshan District Court heard the case on 24 December 2014 but eventually ruled against the plaintiff. Mr He appealed to the Shenzhen Intermediate Court which upheld the original ruling.

Mr He had joined the company as a design assistant on 28 August 2014 and was soon promoted to head of sales. In early November however Mr He was outed after a video of him in an argument with another man on the streets of Shenzhen was posted online. The video came to the attention of his employer who allegedly told Mr He that because the company did not employ homosexuals his employment would be terminated. The boss allegedly cited the psychological impact on customers as his justification.

In March 2016, a transgender man Mr C, filed a complaint at his local labour dispute arbitration committee after he was fired from his job at the Ciming Health Check-up Centre in Guiyang for wearing men’s clothing in the office. “They say I’m a lesbian, and that I damage the company’s image,” he told The Paper. It was further alleged that management told Chen that as health check-up firm it could not employ an unhealthy person like him.

In March 2016, a transgender man Mr C, filed a complaint at his local labour dispute arbitration committee after he was fired from his job at the Ciming Health Check-up Centre in Guiyang for wearing men’s clothing in the office. “They say I’m a lesbian, and that I damage the company’s image,” he told The Paper. It was further alleged that management told Chen that as health check-up firm it could not employ an unhealthy person like him.

Mr C (left) told the New York Times that he went to the manager to explain that he was transgender, not homosexual, and that he was in no way unhealthy, but to no avail. “I was infuriated and surprised,” he said. “I don’t want to be called gay because in that way I’m admitting that I’m a woman. And even if I am gay, how can she say I’m unhealthy? How can a health check-up firm not know that homosexuality is no longer considered a disease?”

The arbitration committee heard the case on 11 April 2016 but rejected Mr C’s complaint in a May ruling, saying the company had not broken the law. He was awarded one’s wages in token compensation. After the ruling Mr C. told the Associated Press:

"I am not satisfied with just the wages. What I want is respect, and respect from the whole of society for minorities like us. I am very disappointed about the result. This (arbitration) process has made me realize that discrimination against sexual orientation is far worse than I had expected, and I will continue to appeal to defend my rights."

In January 2020, however, there was an important breakthrough for transgender rights when a Beijing court ruled that e-commerce platform Beijing Dangdang Information Technology Co. Ltd. had illegally dismissed an employee for “absence of work” after she took two month’s leave for gender reassignment surgery in 2018.

The court ruled that the employee, surnamed Gao, should be reinstated and the company should pay her overdue salary of about 120,000 yuan. The court also said that Gao had the right to use the office’s women’s toilet and that other colleagues should accept her identity and work with her with an inclusive manner.

“Modern society is becoming more and more diverse. We are always finding novelties around us, and we learn to gradually accept them…,” the court said. Despite the court ruling, many transgender people still report difficulties in finding employment because of employers’ prejudices. Many transgender people are self-employed, and a 2017 survey revealed that the unemployment rate for transgender workers was three times higher than the national average.

Laws and regulations related to employment discrimination

Prior to 2008, China’s legal protection against workplace discrimination could best be described as aspirational and inadequate. The Chinese Constitution and several statutes stressed equality of employment but provided little of use in substantively combating discrimination. The 1990 Law to Protect Disabled Persons extended employment discrimination protection to the disabled, and the 1992 Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women provided further details on the rights women were entitled to in the workplace. But the landmark 1994 Labour Law essentially reiterated constitutional articles that employment discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, or religious belief is not allowed.

The vagueness of the laws and a lack of implementing regulations meant that many courts and arbitration committees refused to hear employment discrimination cases, especially if the discrimination occurred prior to the establishment of a labour relationship between the plaintiff and the employer.

Growing public concern and citizen activism over employment discrimination in the mid-2000s however led to the adoption of a number of regulations and policies designed to address particular issues of concern:

- A 2005 amendment to the Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women added a prohibition of sexual harassment.

- 2005 regulations by the Ministry of Personnel established that people with HBV should not be prohibited from civil service positions if tests can show they are not contagious.

- The 2006 ratification of the International Labour Organization’s Convention on Discrimination in Employment and Occupation committed the government to adopt broad policies against employment discrimination.

- The 2007 Regulation of Employment for People with Disabilities required all enterprises to set aside at least 1.5 percent of their workforce for disabled workers.

- In addition to multiple measures to relax hukou restrictions, the State Council issued directives in 2003 and 2006 urging local governments to eliminate discriminatory restrictions on migrant workers.

- A 2007 Opinion by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security declared that it was illegal to discriminate against people with HBV in employment, except for jobs where laws specifically excluded them.

In 2008, the government implemented the Employment Promotion Law, which was both an attempt to solve some of the deficiencies in existing anti-discrimination legislation and establish a broad statement of principle on employment equality. The key advantage of the new law, however, was that it provided victims of discrimination with the means to seek legal redress. The law clearly states that employment discrimination is within the purview of courts, and that workers are entitled to initiate civil lawsuits when faced with discrimination. The law adopts a general anti-discrimination policy, calling on all levels of government to work to eliminate discriminatory employment practices. It expands coverage of the groups specifically mentioned as protected from employment discrimination to include those with infectious disease and migrant workers.

At the same time, the Ministry of Labour and Social Security issued implementing regulations which largely complemented the new law. The regulations prohibited employers from using marriage and maternity conditions in employment contracts, using HBV status as a condition for employment, and discriminating against migrant workers in employment. Unlike previous laws and regulations, which declared prohibitions without penalty for violations, the new regulations established that a 1,000 yuan fine may be imposed on employers for violations of the regulations.

The establishment of a mechanism for legal redress has been a boon for people with HBV. Studies found that, after the law went into effect, more than 70 percent of HBV discrimination cases were accepted in the courts, with more than 200 cases heard by 2011. Prior to the law’s implementation, the anti-discrimination group Yirenping brought less than 20 cases per year; that number immediately rose to 70-80 cases per year after implementation. In addition to bringing more cases before the courts, the stronger laws and greater willingness of courts to accept these cases has also given workers greater leverage and bargaining power in out-of-court settlements.

As noted above, anti-discrimination activists have had some success in bringing lawsuits on the grounds of gender, hukou and HIV discrimination but many courts are still wary of accepting cases that push the boundaries of judicial practice. Moreover, many anti-discrimination activists, particularly those associated with Yirenping, have been subjected to a concerted government crackdown that has made it much harder to operate and provide advice and services for those discriminated against at work

Deficiencies of the current laws

The Employment Promotion Law clearly remains deficient in several areas of administration, effectiveness, and coverage.

- The law relies on under-staffed and over-worked local labour bureaus to oversee and implement anti-discriminatory policies and regulations.

- Since prospective employees are not actually employees under the law, cases of employment discrimination in hiring are not subject to the labour dispute arbitration system and victims must use the formal court process, which can cost a lot more and can take much longer to complete proceedings.

- Fines for violations of the Employment Promotion Law are hopelessly inadequate. A 1,000 yuan fine for conducting HBV screening does not deter employers from conducting such tests. Moreover, employers can simply require individuals to sign documents indicating that they took the test “voluntarily.”

- The law states that those who have been discriminated against are entitled to initiate legal proceedings, but it offers no explanation to the courts on what standards are to be followed, what types of compensation should be paid to victims and what punishments should be meted out to violators. Chinese courts are known to be unwilling to hear cases without regulations or laws that adequately explain how cases should be tried.

- The law remains limited to protecting against five types employment discrimination: gender, ethnicity, disability, individuals with infectious diseases, and rural migrants. The lack of coverage for other types of discrimination, such as age, religion, height and sexuality, all of which remain commonplace in China, also limits the law’s effectiveness.

Conclusion and recommendations

The Employment Promotion Law was heralded as a significant development in the fight against employment discrimination in China, but its effects on the ground have been relatively muted. Employment discrimination is still widespread and the enforcement of anti-discrimination policies remains wanting, despite some progress.

China’s civil society organizations have been instrumental in pushing for greater tolerance and equality in the workplace, particularly in their use of lawsuits and social media to name and shame discriminating employers. The higher exposure of employers to lawsuits and the negative publicity generated by them has led many to adopt less discriminatory practices and has encouraged local governments to take discrimination more seriously. However, the Chinese government’s well-documented crackdown on civil society organizations that began in 2014 has stalled much of the progress made in recent years and may have been turned the clock back.

It is vital that the Chinese government not only allows civil society to play a role in tackling discrimination but takes additional measures itself to bring the fight against discrimination to the next level. With this in mind, China Labour Bulletin recommends the following:

- Expand the coverage of anti-discrimination legislation to include widespread forms of employment discrimination such as those based on age, height and physical appearance, personal beliefs and sexuality.

- Authorize labour dispute arbitration committees to take on and adjudicate in employment discrimination cases, thereby reducing the time and costs currently borne by litigants in the civil courts.

- Increase the fines levied on employers from the current level of 1,000 yuan per instance to at least 50,000 yuan per instance.

- Clarify the court procedures to be followed in anti-discrimination cases and specify the forms of compensation available to victims and the punishments required for violators.

- Establish a comprehensive government body tasked specifically with tackling employment discrimination, similar to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the United States. Such a bureau would be charged with implementing anti-discrimination laws, and have a formal system to investigate and mediate complaints of employment discrimination, and offer to sue employers on behalf of victims.

The implementation of the above measures would demonstrate to employers and civil society that the Chinese government is serious about equality in the workplace and is willing to provide the necessary resources to local government departments, the courts and labour arbitration committees to combat employment discrimination.

This article was first published in November 2012. It was last updated in July 2020.