Worker’s legal action highlights the years of injustice endured by Changsha’s street cleaners [1]

24 June 2015In February 2012, 65-year-old Xie Ruofan was laid off from his job as a street cleaner in the central city of Changsha. He had worked there for 25 years with hardly a day off but all his employer, the Furong District Environmental Hygiene Department, was prepared to offer Xie and his similarly laid-off colleagues was a derisory 200 yuan for every year of service.

This was the final straw for Xie who had put up with decades of low pay and poor working conditions. The Environmental Hygiene Department had never signed a formal employment contract with Xie, never paid any social insurance contributions, overtime or any of the other benefits he should have been entitled to. In fact Xie told the China Youth Daily [2], the only bonus he had ever received in a quarter of a century’s service to the city was a 2,000 yuan allowance for taking part in Changsha’s 2011 National Civilised City campaign.

Xie was not alone: A survey by the China Youth Daily in 2014 showed that the vast majority (around 70 percent) of Changsha’s 11,000 sanitation workers were classified by the government as temporary hires. Like Xie, they did not have an employment contract and had no social insurance. Once laid off, they would have no means of support, no pension and no medical insurance.

Xie decided to take action; not just for his own sake but for the thousands of other sanitation workers in the same position. On 27 March he went to the Furong District Labour Inspectorate to demand payment of his social insurance arrears. The next day he took his case to the local labour dispute arbitration committee. Both the inspectorate and the arbitration committee refused to accept his case on the grounds that Xie had been employed as a service provider rather than as a formal employee, and thus was not protected under labour law and could not file for labour arbitration.

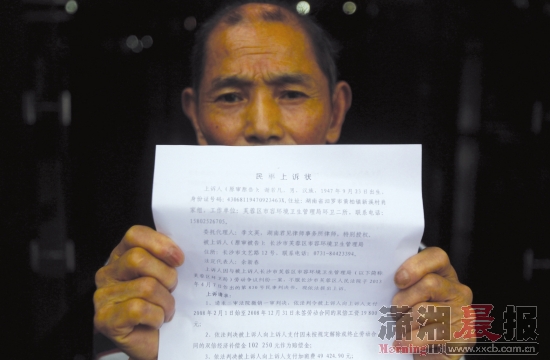

Xie Ruofan goes to court. Photograph: Xiaoxiang Morning News (潇湘晨报)

This rejection did not deter or slow Xie down. He immediately filed a civil lawsuit in the Furong District People’s Court, seeking more than 260,000 yuan from the Environmental Hygiene Department in economic losses and damages. In doing so, he reportedly became the first sanitation worker in Hunan to take legal action against the local government for violation of labour rights. The court tried to mediate proceedings and urged the Environmental Hygiene Department to come up with a comprehensive settlement for all the laid off sanitation workers. However, the department refused to improve upon its original compensation offer of 200 yuan per year of employment.

The following year, Xie sought the help of the local Procuratorate and, on 10 May 2013, the court reopened the case. The Environmental Hygiene Department argued that since Xie was five years over the statutory retirement age when he was laid off, he did not have a labour relationship and therefore could not claim compensation under the terms of the Labour Contract Law. With regard to his claims for overtime, the department said it operated a “subcontracting by road-section system,” which meant that wages were based not on hours worked but on the area of road swept.

However, the district court ruled that Xie had a de facto employment relationship with the department and ordered that Xie be paid 51,125 yuan in compensation. Xie considered the amount inadequate and appealed to the Changsha Intermediate People’s Court.

In April 2014, the appeal court ruled that Xie was only entitled to 6,200 yuan for overtime worked on statutory holidays during the two years prior to being laid off. In September 2014, Xie filed a petition with the Hunan Higher People’s Court demanding that the Intermediate Court re-hear his case. The case was heard again in May this year but no date has yet been set for the ruling.

One of the key legal issues complicating Xie’s case is the legal status of workers who have exceeded the statutory retirement age: Under what circumstances can they still be considered workers rather than service providers, as the Furong Environmental Hygiene Department claimed? Article 44 (2) of the 2008 Labour Contract Law states that a worker’s employment contract ends when “the worker starts to receive a basic pension, in accordance with the law.” However, the State Council’s Implementing Regulations for the Labour Contract Law, states in Article 21 that a worker’s employment ends when they reach the legal retirement age.

To complicate matters further, Article 7 of the Supreme People’s Court’s Interpretation (III) of Several Issues on the Application of Law in the Trial of Labour Dispute Cases, issued on 14 September 2010, states that “in the event of dispute with employers, employees who have received lawful state pension benefits or who have received retirement payments shall take legal action at the People’s Court and the People’s Court shall handle such cases based on the provision of labour services.” However, there are no clear provisions on the status of workers who have reached retirement age but who have not yet received a state pension.

This legal grey area has presented numerous problems for sanitation workers, who often have no choice but to work well beyond the retirement age. In 2013, five sanitation workers in the southern city Foshan [3] were denied wages, overtime and social insurance in arrears by the local arbitration committee because they were over the statutory retirement age. Labour lawyers have pointed out this defect in the law on numerous occasions but there seems to be little pressure on China’s courts or legislature to clarify the matter once and for all.

The one cause for optimism in Xie’s case is that following the China Youth Daily’s 2014 article, the Changsha Municipal Party Committee promised that it would look into the provision of social insurance for the more than 8,000 temporary sanitation workers currently employed in the city. In Furong, the authorities claimed they had already stated paying social insurance for the district’s temporary workers; however it was unclear how the issue of social insurance contributions in arrears would be addressed. The newspaper estimated that the total arrears bill for the more than 1,700 temporary workers in Furong district would be more than 40 million yuan.