From Dongguan to Phnom Penh, its déjà vu all over again [1]

13 March 2015The supervisor on the floor is a relative of the boss and he doesn’t understand a damned thing. He’s simply not up to the job of being a manager: he only knows how to scold people. He knows that in one hour you can only manage to do 15 pieces, but he sets the quota at 50. If you can’t meet the quota, then you have to put in extra hours. But there’s no overtime pay for that. They say “other people can meet the quota, so why can’t you?” In fact, no one can ever fill the quota in time.

Interviewee in Dongguan factory 2004

“You woman - you must learn to use that machine faster. Otherwise you can leave the factory. Do you understand?” And he would throw the materials we were supposed to stitch on the machine or on us, and bang the desk and come close to our face and scream. He is very harsh.

Interviewee in Cambodian factory 2014

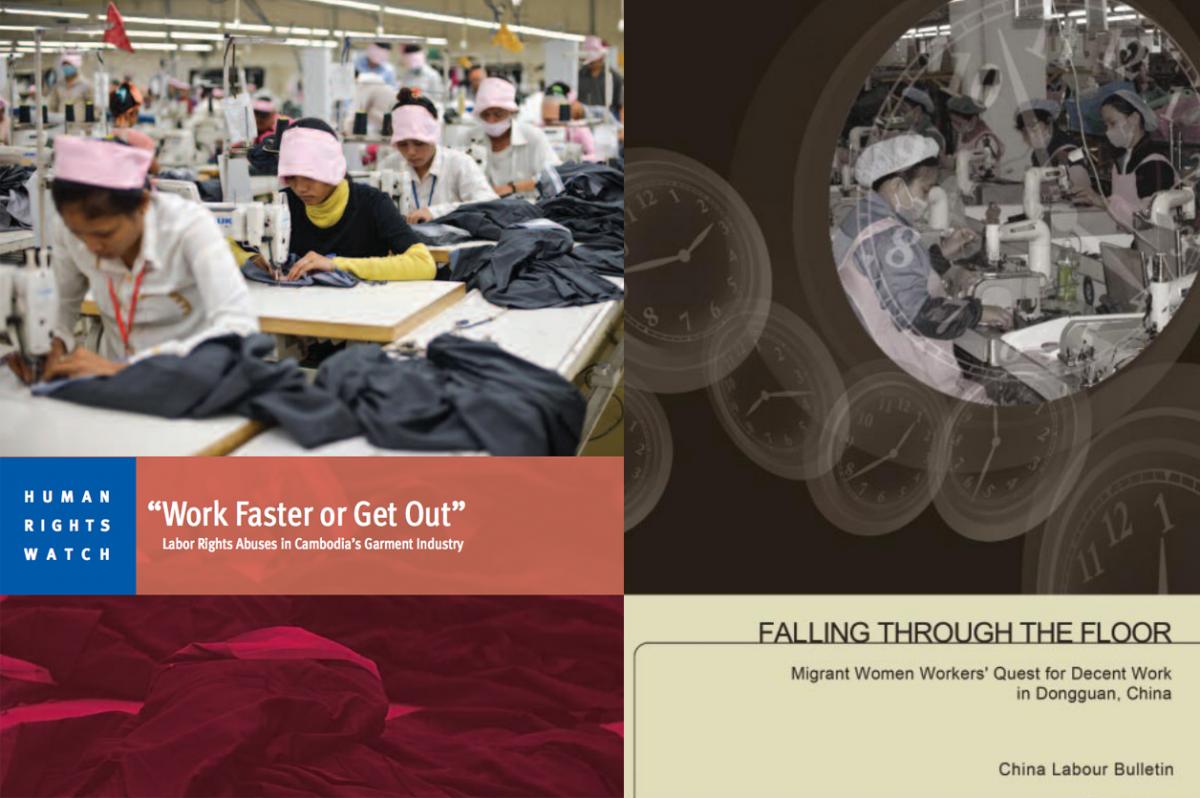

In 2004, China Labour Bulletin investigated the pay and working conditions of migrant women workers in Dongguan [2], China’s “factory to the world.” In 2014, Human Rights Watch investigated the pay and working conditions of the predominately women workers in Cambodia’s garment industry [3]: The results were predictably similar.

Work Faster or Get Out [3] Falling Through the Floor [2]

Most of Cambodia’s garment factories are owned by Chinese, Taiwanese, Hong Kong and South Korean companies, and many of them set up shop in the suburbs of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh when production costs in Dongguan got too high. They produce goods for the same international brands that bought from Dongguan in the 1990s and 2000s, and operate basically the same low cost, low margin, labour intensive business model.

The minimum wage in Dongguan in 2004 was just 450 yuan a month (US$54 at 2004 exchange rates). A combination of labour shortages and increased labour activism pushed wages higher and as of 1 May this year, the minimum wage in Dongguan will be about four times higher, standing at 1,510 yuan per month or US$241 at today’s exchange rate.

In 2004, the minimum wage for Cambodian garment workers was US$50 per month, about the same as in Dongguan. However, wages increased much more slowly in Cambodia and it was not until the upsurge in worker and trade union activism in 2013 that the minimum wage reached US$100 per month on 1 February 2014. Protests over low pay continued last year and the minimum wage was raised again in January this year to US$128 per month.

At no time however, in either Dongguan or Cambodia has the minimum wage been a living wage. Workers always had to rely on overtime and bonuses just to get by, and, as both reports point out, this frequently led to abuses with employees being forced to work excessive overtime. The CLB report found that most women factory workers in Dongguan worked 12 to 14 hours a day, seven days a week. Similarly, HRW found that most employees worked 11 to 13 hours a day. The excessive workload took a terrible toll on workers’ health but if they complained or refused to do overtime they were penalized with fines or were fired.

Both reports highlighted the oppressive management regimes and the tactics used to get rid of pregnant women workers. In Dongguan, if women wanted to keep their jobs after giving birth, they would have send their baby back to their home town after one month or bring their mother to Dongguan to look after it. In Cambodia, factories use a system of fixed short-term contracts in order to screen out visibly pregnant employees.

The good news is that, just as workers in China have successfully used concerted collective action to push for better pay and conditions, workers in Cambodia are now doing the same. The difficulty for workers in Cambodia however is the critical role of the garment sector in the national economy.

In 2013, Cambodia’s total exports amounted to roughly US$6.48 billion, of which garment and textile exports accounted for $4.96 billion. In 2014, garment exports reportedly totalled US$5.7 billion. The industry is a major source of non-agrarian employment with more than 700,000 workers. As such, the authoritarian government led by Hun Sen wants to make sure the garment industry stays in Cambodia and has already demonstrated its willingness to use brute force to supress worker activism.

Cambodia’s workers need support and hopefully the publicity already garnered [4] by the HRW report will help bring about that support.