Developing workers’ theatre in China [1]

13 December 2013Benjamin Teare is the director of New Common Theatre, a company currently developing a theatrical production devised by and featuring Chinese workers and to be staged in factories across China. In preparation for the production, Ben travelled extensively from Guangzhou to Beijing to Kashgar, talking to workers, artists, factory owners and trade union officials.

In an article, written for China Labour Bulletin, Ben describes his journey thus far and his plans for the project next year.

Wong Chun-Tat and I met at theatre school in Paris. He is a performing artist. His family is from the coastal city of Dongguan in southern China. His aunts and uncles are workers on assembly lines. Chun-Tat invited me to China to develop a piece of theatre about factories.

When I arrived in China ten months ago, I knew next to nothing about workers. I cannot recall quite what I had expected, but in preparation for this article, I reread a few pieces written by me on the subject in November 2012. I realise that I had conceptualized ‘labour.’ I thought about it through the lens of Fritz Lang in his 1927 science-fiction masterpiece Metropolis (see photo below), in which an underclass of workers are kept underground. Millions of people shuffling in and out of vast assembly lines. Shifts. Uniform. Grey. Depressing. What little I knew about workers – indeed about Chinese modernization – had become an aesthetic. I have found that it is easy to do this with things outside of our experience.

Once on the ground, I discovered three things first.

1. Most people working in factories are young (an estimated 61percent of China’s 266 million migrant workers are aged between 16 and 30)

2. This young group of some 160 million people feels disempowered and frustrated by their situation.

3. There is a workers’ movement that uses theatre as a source of empowerment.

As an actor and theatre maker, I was most interested in the last of these discoveries – but I could not see why or how theatre was helping. Rights based advocacy among workers I could understand, but what can theatre do, really?

* * *

Guangzhou East Railway Station. March 2013. It is the end of the Spring Festival, and the station is flooded with people. I have in my pocket a few contacts from Chun-Tat’s childhood friend, a student of traditional Chinese medicine. The next day we are to meet a young watch factory owner and a handbag manufacturer for lunch. I want to get into factories as soon as possible.

At lunch, the factory owner – Enoch – tells me that if my aim is to make a piece of theatre about factories, I have arrived too late. “Chinese workers are lazy these days” he says, “factories are moving to Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia. If you want to make your play about the modern Chinese proletariat, you should go to offices. Everybody works for design companies now, or telecommunications.” After lunch, we get into his BMW and drive to the family watch shop. There we eat dried prawns and drink boiled water out of plastic cups. “Are you a Christian?” he asks. “No” I say. “Oh. I am.”

Enoch plays piano in a Christian rock band. On the way to his factory, we listen to a track called ‘Life is a show on God’s TV.’ The factory has a church attached to it. Enoch’s dad is the pastor. When we arrive, I am introduced to the rest of the band. They are all factory owners from the city of Wenzhou, a three hour drive south west of Shanghai. They have converged on the church for their weekly band practice. When it is through, the singer improvises a prayer into a microphone. A young man in glasses begins to cry, with one hand on his heart, and another in air, heavenwards. Hallelujah.

I meet a Syrian buyer at Tomatoes pizza joint, at three in the morning. His name is Radwan. Through a haze of shisha smoke, he agrees to bring me to one of his suppliers in Chaozhou, another Guangdong factory town, and a six hour bus ride east of Guangzhou. His ‘trade’ is ladies ball gowns and evening dresses. His method is as follows: he goes online, picks ball gowns he likes the look of, gives them to his designers – a kind man from the Philippines and his nephew – to rework and pick fabrics for, then he gets this Chaozhou factory to knock them up. Once made, he punts the dresses to friends in Lebanon, Syria and across the Arab world. Because this cash-actually-does-grow-on-trees formula is so incredibly easy to emulate, Arab-world buyers are ruthlessly territorial, and use scare tactics to deter would-be rivals. Over strong black tea made syrupy by sugar, and cream cheese and mixed-fruit jam rolled up in Lebanese flatbreads, I am told of drive-by shootings, arson and death threats. It is an ugly business. For lack of furniture in his newly rented Chaozhou flat, Radwan and I share a bed. One night, as he slips hairily beneath the covers, I wonder what sequence of events led me to this moment. But the thought does not last long, and I am soon lulled to sleep by that oft heard Guangdong duet: the snores of a buyer mingled with the strained notes of the KTV bar over the street.

“You will have to come back with formal permission from the Hubei provincial government.” I am sitting in a reception room at Foxconn, Wuhan. The public relations officer refills my tea. He found me interviewing new recruits outside a dormitory. “We put on performances for the workers, at Mid-Autumn Festival and Spring Festival” he said “but never foreign performance groups.” “I see.” “May I ask, why do you want to perform for the workers?” “Because I have spoken with several of them, and they want something different to the variety shows you normally program.” “How different?” “You mean what will the show contain?” He nods “I can’t tell you for sure. We haven’t written it yet. We prefer to w…” “Yes, you will have to get government permission before we can agree to host such a performance.”

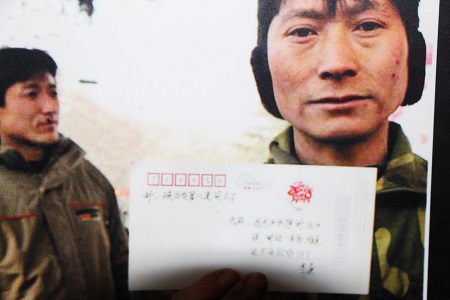

“Why did you quit?” “Well, you know, I just graduated, and I was very proud. After all, I am a college student and I have greater ambitions than working in factories.” Wang Wei (see photo below) lights a cigarette. He is twenty-three. We are sitting on bunk beds in a dormitory at the Taigong Iron and Steel plant in Taiyuan, Shanxi. “Is the work better at this factory?” I ask “the work here is about the same: eating, working and sleeping. It’s too unchallenging.” When Wang Wei graduated from technical college, he moved to Beijing. His cousin said he could find him work in sales. For two years, he sold apartments, but he did not like his boss, so he quit and moved to Inner Mongolia, attracted by a government stimulus scheme. In the city of Ordos, he started a general store with a partner. He soon tired of that “It was too cozy and predictable. There’s a saying: ‘peace and comfort can’t nurture great men.’ ” So it was that Wang Wei came back to Taiyuan to work in a factory making moulds and steel parts for heavy industry. “I want to save up and start my own breakfast place” he says, taking a long, brooding toke on his cigarette.

“What do you mean you want to put on a theatre show at this mine?” the guard thinks I am out of my mind, “Well, just that – I’ve been speaking to some of the miners, and they haven’t seen theatre before. They say they want to, because…” “They say they want to! Ha!” This is a state-owned mine in Shanxi, the heartland of China’s coal industry. “So, you actually want to turn up here with actors and music and do a show for the miners?” “Yes.” “Ha! Impossible!”

Xu Duo is on crutches. He fell over at one of his gigs. He shows me around the migrant worker museum the New Workers Art Troupe has built. Poems written by migrant workers, photocopies of correspondence between factory managers and injured workers, injured workers and the labour bureau, the labour bureau and factory managers. Round and round. Testimonies. A time line of rural-urban migration since 1979. Slippers made by a young woman who threw herself off a dormitory building at a Foxconn factory. A rickshaw. “This is our theatre” Xu Duo leads me into a big black tent, “a Japanese performance troupe left it for us. We do weekly performances in here, for the community.” Xu Duo is the elected leader of the troupe. He came to Beijing to learn guitar at a music academy, but could not afford the fees, so he taught himself. He busked and played in bars, where he met New Workers Art Troupe’s founder, Sun Heng. They became firm friends. “The band plays all over, on construction sites and plazas, at festivals and in bars. And we record albums. We built the community school with the proceeds of our first album.” The motto of the New Workers Art Troupe is ‘Labour is glorious.’

“We’re on a six month placement from our technical college in Gansu.” The young men sweat. They are being made to practice a marching routine in the desert heat. Tomorrow, management and the big bosses will gather to watch them. Their marching has to be just right. “What happens at the end of the six months? Will you leave the Xinjiang?” “If we like it here at the petrochemical plant, we can stay on.” “And do you like it?” “No.” “So you’ll go elsewhere?” “No, we’ll stay.”

I have started to receive invitations to run theatre workshops at workers’ community centres across China. As well providing legal advice and training sessions, the centres offer companionship, support, camaraderie, encouragement and, crucially, a safe space for the expression of daily pressures and problems. The people founding and running these centres are often former factory workers. Most have come to social work by way of first-hand experience as a complainant in a labour dispute, usually related to an injury in the workplace. Staff at labour rights groups often have missing fingers and gnarled forearms.

The centres face a host of obstacles when doing rights advocacy:

1. Workers can be shy about speaking in front of a group or factory management, making it tough to find representatives.

2. There is a lack of social recognition around rights.

3. Because most workers are migrants from various regions across China, it can be difficult to build a sense of solidarity and common purpose among them.

4. Managers often use bullying tactics to deter representatives from doing collective bargaining.

The workers’ theatre movement is happening because workers see drama as a platform for building recognition around rights and rights advocacy, both among themselves and out in their communities. Theatre brings rural-urban migrants from various provinces together to create collaboratively, generating a strong sense of shared experience and common purpose. At the same time, it teaches self-confidence and affords workers an opportunity to make their voices heard, not just by managers and other workers, but across China and internationally.

“Just do something to relax the workers” says the deputy chairman of the trade union at a smartphone factory in Huizhou, Guangdong – reflecting on the ‘slightly too agitating’ performance Liu Chao and I just did in the canteen, for an audience of 3,000 staff. “Something to make them feel happy,” Ms. Wong adds. She is the PR manager for the factory. “Maybe something that makes them think that the smart phones we make are really an excellent product,” the union man chews thoughtfully on his slightly-better-than-what-they-get lunch. We are sitting at one of the nicer tables, in the nicer, screened-off, managers’ part of the factory canteen.

“If we don’t try to solve workers problems when we do theatre,” said an injured worker at Nanfeiyan legal advice centre in Foshan, “then there’s no point doing it.” There are recurring themes in the theatre workshops I have been involved in: remembered childhoods in the countryside; sacrifice (of parents for their children, of children for their parents); injury; greedy factory owners; domestic violence; trickery (in the form of pyramid schemes or the false promise of employment); pressure from home (to marry); the difficulty of finding a partner; absurd processes of litigation. Workshop participants are usually workers from nearby factories. Sometimes they tell their own story. Sometimes they share it with another workshop participant, who will in turn share it with the group, on behalf of the person it happened to. The latter method has been quite effective. Generally speaking, it is less awkward to tell someone else’s story, and you tend to tell it with more generosity than if it had been your own. Sometimes we enact the stories as a group. A workshop I did recently in Shenzhen was attended by migrant workers from Hunan, Sichuan and Guangxi. Wang Xingan remembers creeping into a neighbour’s orchard to steal fruit, under the cover of night. Xiao Yang’s most vivid memory is being rescued from drowning in a reservoir as a boy of eight. Xiao Ye can still hear cattle as he drives them across the landscape of his childhood. Da Huang remembers the journey: four days and four nights to arrive at a factory. Others tell of a short lived romance and the difficulty of finding love; some about betrayal, some about injuries and unfair dismissal. We put the stories together, in chronological order – beginning as children in the countryside, and ending as adults in the factory. When the group came to do the performance, the audience – workers from nearby factories – heard the stories as one narrative, even though they belonged to different people from various parts of China. An audience member from Hunan stood up afterwards and said “I thought those stories belonged to just one person. Hearing that they belong to different people, from Guangxi and Sichuan, well, I don’t know why, but am moved by that.”

* * *

Rural-urban migration in China since the late 1970’s constitutes the single largest human migration in history. There are so many stories rising up from it and being reabsorbed by it. In the workshops, there is often a sense of shared experience. And it is this shared experience that is at the core of our project.

My company New Common Theatre has done performances and workshops in canteens and community centres, on factory floors and plazas, and at workers’ conferences. We are working towards doing a big show next year, in collaboration with labour NGOs in Guangdong, Beijing and Tianjin. The show is being developed by the cast (some of them professional actors, some of them workers), and we are bringing in an orchestra and projection mapping artists to deal with the scale of some of our audiences and venues, which include the biggest shipyard in China – a 3.3 million square metre site in the eastern city Qingdao – a smart phone and tablet factory employing 32,000 people, and plazas in Guangdong and Shanxi provinces for audiences of up to 11,000.

Hong Mei has opened the Sunflower Women Worker’s Centre in Guangzhou early to meet me. She is clear and composed and has definite ideas about our project:

“It is not that workers are reluctant to speak up” she says “it is more structural. Factories do not give workers an opportunity to express themselves, so they remain silent. Factory managers are not to blame for this. It is not their personality – it is the position they occupy. This is what your theatre should address.”

For further information on New Common Theatre and workers’ theatre in China please contact Benjamin Teare at benjamin.teare@gmail.com [2]