Strikes surge again in September led by disputes in the service sector [1]

08 October 2012By Jennifer Cheung

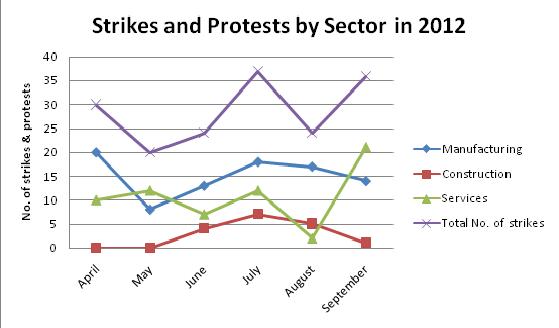

The number of strikes in China’s service industries surged once again last month to overtake manufacturing as the country’s most strike prone sector, according to data compiled by China Labour Bulletin.

Out of the 37 strikes and protests recorded on CLB’s strike map [2] in September, over one half (21) occurred in the service sector, including seven in transport, six in retail and two in education. A total of 14 strikes were recorded in the manufacturing sector.

The surge in service sector strikes corresponds to a HSBC note published 8 October which said new order volumes at service companies continued to rise at the fastest rate in four months while new orders placed at manufacturing firms continued to fall in September.

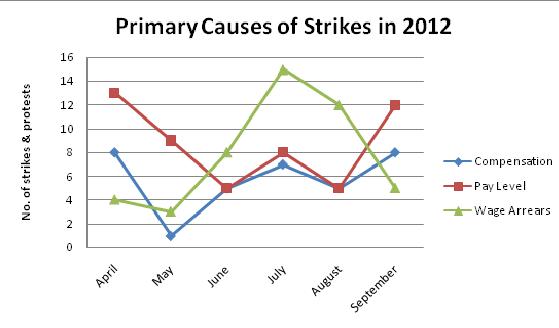

Demands for pay increases (12 cases) were the primary cause of strikes and protests in September, followed by demands for better compensation (eight cases) and wage arrears (five cases). Other causes of strikes and protests included demands for overtime pay and social security. In addition, bus and taxi drivers in China’s coastal provinces staged protests complaining about unlicensed taxis, high license fees, rising fuel prices, and low fares.

Despite the continuing slowdown of China’s manufacturing sector, workers in eight factories, mainly in the Pearl River Delta, went on strike for better pay. In four Japanese-owned factories in Guangdong and Shenzhen, workers also protested the Japanese government’s “purchase” of the Diaoyu Islands earlier in the month.

Although foreign-owned companies suffered most from strikes in September, protests also affected state-owned enterprises and public institutions such as schools. For example, construction workers protested at a state-owned hydropower station in Guangdong and workers at a brewery in Sichuan protested against a share repurchase plan. In Hunan, bank employees protested the termination of work contracts; teachers at a rural school in Guangdong demanded a pay increase, as did workers at an aerospace factory in Guizhou. There were, in addition, two sanitation workers’ strikes in Guangxi and Guizhou, caused by low pay levels and social security disputes respectively.

In terms of the response of the local authorities to worker protests, police were deployed at 11 strike locations and the local labour bureaus reportedly intervened in seven disputes. Transport strikes usually drew a swift response from the municipal government, transportation and public security departments, promising to address drivers’ concerns and sometimes detaining strikers on charges of disturbing normal transportation order. During a taxi strike in Guangdong [3] on 12 September, for example, five suspected strike leaders were detained after a ten hour rally at a train station protesting unlicensed taxis and high contract fees.

Workers were also briefly detained during an anti-Japanese strike in Guangdong, an anti-layoff strike at a solar power company in Jiangsu, and during a strike at a Hong Kong-owned leather products factory in Guangdong.

While government intervention has become the norm after workers’ collective protests, the immediate motivation of the authorities is more likely to lean towards maintaining social stability than actually solving the labour dispute that gave rise to the conflict. A security guard who took part in a strike at a Taiwanese-owned chemical factory in Dongguan, for example, said the local labour bureau left after making workers and management sit at the negotiation table but without giving much instruction on how the negotiations should be conducted. The strike occurred on 25 September and ended before the National Day Holiday, but the conflict persisted, with both sides failing to reach an agreement as of 5 October.