Local governments more active in labour dispute resolution [1]

08 June 2012By Jennifer Cheung

Local governments took a far more active role in dealing with strikes and worker protests in May, directly intervening in half the cases recorded on CLB’s strike map [2] last month.

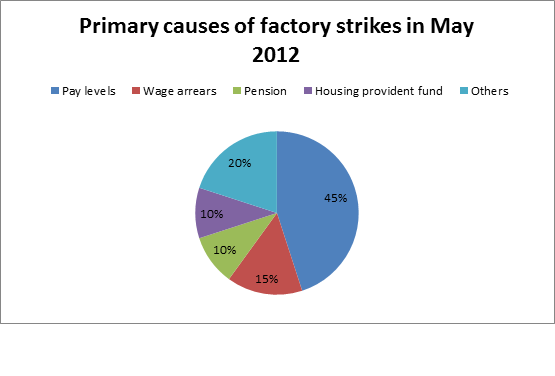

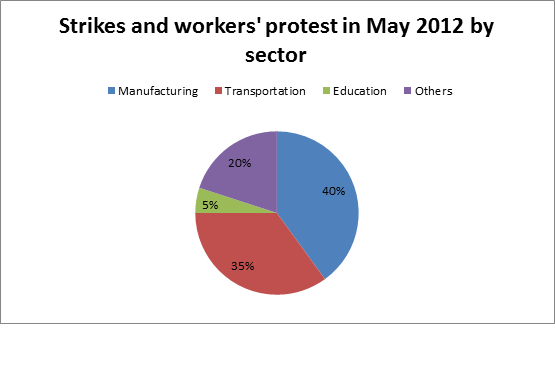

Local governments intervened or mediated in nine of the 20 strikes recorded in May, compared with just one such intervention in April. Pay demands once again dominated workers’ complaints with nine cases last month, and the manufacturing sector was once again the major source of strikes, primarily in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and foreign invested factories.

Collective bargaining or negotiations with management started in three cases, while police were reportedly deployed in seven cases. Dozens of workers at a Hong Kong toy maker in Dongguan and a logistics company in Nanchang were detained during their protests.

Transportation strikes by bus and taxi drivers increased by three cases to a total of seven last month. Taxi drivers in Lanzhou, Hainan and Zhejiang staged protests against unlicensed taxis and public transport competitors. Bus drivers in Ningxia, Shandong and Shenzhen went on strike against the increasing number of market rivals, wage arrears and poor remuneration.

Guangdong remains the most strike packed province in China, followed by the Yangtze River Delta, Yunnan and Hainan. In Wenzhou, around 1,000 angry migrant workers took to the streets [3] in late May, demanding that government bring to justice the boss who beat a migrant worker to death over a wage arrears claim in mid -May. Several hundred rural teachers [4] in Guangxi took some of the limelight too as they staged protests outside municipal and provincial governmental buildings demanding a fair and reasonable pension plan. One teacher was said to have committed suicide because of the heavy pension burden. The latest data [5] released by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security showed only 16.38 percent of migrant workers have pension plans.

Government intervention in labour disputes can be both a blessing and a curse for workers. Local governments can certainly force employers to accommodate workers’ demands but at the same time they can pressure workers into accepting a deal that only goes partway to meeting their demands and certainly does not address the root causes of their grievances.

Moreover, as the recent issue [6] of Collective Bargaining Research (集体谈判制度研究) shows, government intervention can be a costly and time consuming process for all sides in the dispute.