As urbanization continues, will Cantonese and dialect usage increase? [1]

09 October 2009

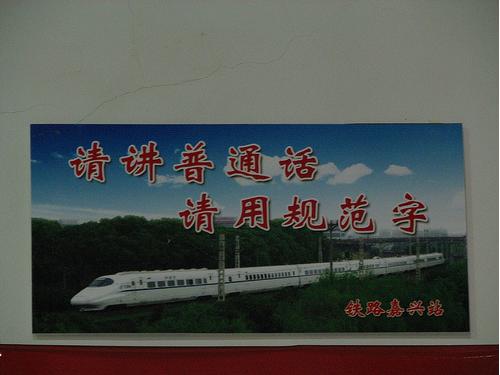

And yet, a recent South China Morning Post article [4] points towards a limited revival in the fortunes of Cantonese in Shenzhen. As it is now, many migrant workers to Guangdong come from the broad Mandarin-speaking areas of China in the northern and south-western parts of the country. Generally speaking, they are unable to learn the local language, due to lack of classes and the large amount of time that they spend working. However, some of the children of migrant workers − the second generation of migrant workers who have often grown up in the cities – are enthusiastic about speaking Cantonese in Shenzhen, partly as a way of asserting their new identity as Shenzheners.

Li Zhen is a 16-year-old high school student who was born in Wuhan and moved to Shenzhen at the age of 10. She insists on talking to her friends in Cantonese.

"My parents do not speak Cantonese and we speak Putonghua or Wuhan dialect at home," Li said.

" …in school, we only speak Putonghua in class. (But) all my friends are Cantonese speakers. Cantonese is the fashionable language among Shenzhen teenagers."

Li's friend, Wang Zijing, said speaking Cantonese made them feel more international.

In contrast to this example of harmony and cohesion between locals and the children of migrant workers, the CLB report “the Children of Migrant Workers in China” found that there were often many strains in the relations between local and non-local children [5]. For example, a survey in Guangdong found that 58 percent of students in migrant schools did not like or even hated local children, 26 percent said they disliked locals because they were bullies, and 37 percent said city children looked down on them. Nonetheless, the studies indicate that roughly 1/3 to 2/3 of non-local children have local friends, and would thus seem to fit it well socially.

The SCMP article also suggests that many people are learning Cantonese in Shenzhen because they precive it to be cool, sophisticated, cosmoploitian, and to take advantage of the commercial benefits that could come from working with Hong Kong people and Hong Kong-dominated industries.

However, from a second language acquisition theory point of view, it is in some ways completely predictable that the children of migrant workers who get along well with local kids are able to easily pick up Cantonese and enjoy it, since the kids become part of the "club" or "in group". Speaking about the importance of feeling like a member of the "group" in acquiring a second language, Second Language Acquisition expert Stephen Krashen explains [6]:

It is true that studies of immigrant children show that those who begin second language acquisition before puberty tend to develop native accents and those who start later typically do not. It is also true, however, that many who start later develop excellent accents, very close to native, and many who start foreign languages young do not. For example, "heritage language" speakers, those who speak a minority language at home (e.g. American-born Chinese living in the US) often speak the heritage language with an accent, even though they have been hearing it and speaking it their entire lives. In addition to age, another variable appears to be at work, what Smith (1988) calls "club membership": we acquire the accents of the group we feel we are a member of, or feel we can join. This explains why children do not talk exactly the way their parents talk - they talk the way their friends talk (emphasis added).

From this point of view, for the children of migrant workers who have developed many local friendships, speaking Cantonese is evidence that they have become members of the “club”, and are no longer outsiders. It’s also a way to differentiate themselves and protect themselves from some of the cruder forms of prejudice that the migrant who just arrived might encounter. This phenomenon is probably also evident in places like Shanghai, where speaking Shanghaiese can be seen as a very sophisticated and fashionable thing (at least among certain people).

All this seems to show that the second and third waves of urbanization will most likely be quite different form the first waves that took place after “Reform and Opening” (1978-now). Socially speaking, the lines between city resident and nongmin might blur, and China may see a new wave of assertions of regional and ethnic identity (such as a revival in Manchu identity, as reported in this Wall Street Journal article [7]).

Thoughts?