Increase in strikes in logistics and service sectors in 2021 not expected to let up

15 February 2022Based on emerging trends, CLB had predicted that in 2021 workers would face a less stable living environment. Economic restructuring and competition between companies would mean that workers continue to resort to strikes and collective action to resolve labour disputes. These predictions have come to pass.

In 2021, CLB’s Strike Map recorded 1,093 worker strikes, an increase of more than 200 from 2020. This takes total actions closer to pre-pandemic levels, with 1,385 logged in 2019, for example.

The number of strikes involving logistics workers increased rapidly compared to 2020, while protests of service industry workers occupied a significant proportion of the whole. Grievances from the rising service industry may still be underestimated - as we have seen in our Calls-for-Help Map, which collects individual worker disputes rather than collective ones - that an increasing number of young service sector workers have complained and documented their labour conditions on social media, in search of assistance.

Price wars between parcel delivery companies have resulted in lower wages for couriers. Some workers have had to accept rates of less than 1 yuan per order. Underpaid couriers initiated strikes when management slashed their wages. Meanwhile, strikes of food delivery workers increased from just 3 to 13 cases in 2021, mainly protesting pay cuts.

Taxi drivers have borne the brunt of higher operating costs due to hikes in oil and natural gas prices. Ride hailing price wars and volatile markets meant that last year, the Strike Map recorded 150 strikes involving taxi drivers, up from 116 in the previous year.

Taxi drivers have started petitions and gone on strike in the hundreds. They tend to demand self-employment and more independence from management companies, as these middlemen often take hefty cuts and do very little for the drivers. Workers also demand taxi management and vehicle ownership rights be integrated.

The consumer demands of China’s new middle class have shaped the pressures that workers face and the nature of the industries in which strikes are concentrated. Workers are left unpaid when restaurants and gyms go bankrupt. The crackdown on education last year meant teachers lost jobs and pay. Last year, 158 strikes involved service workers and 53 involved educational and training institutions.

Photograph: Wang Sing / Shutterstock.com

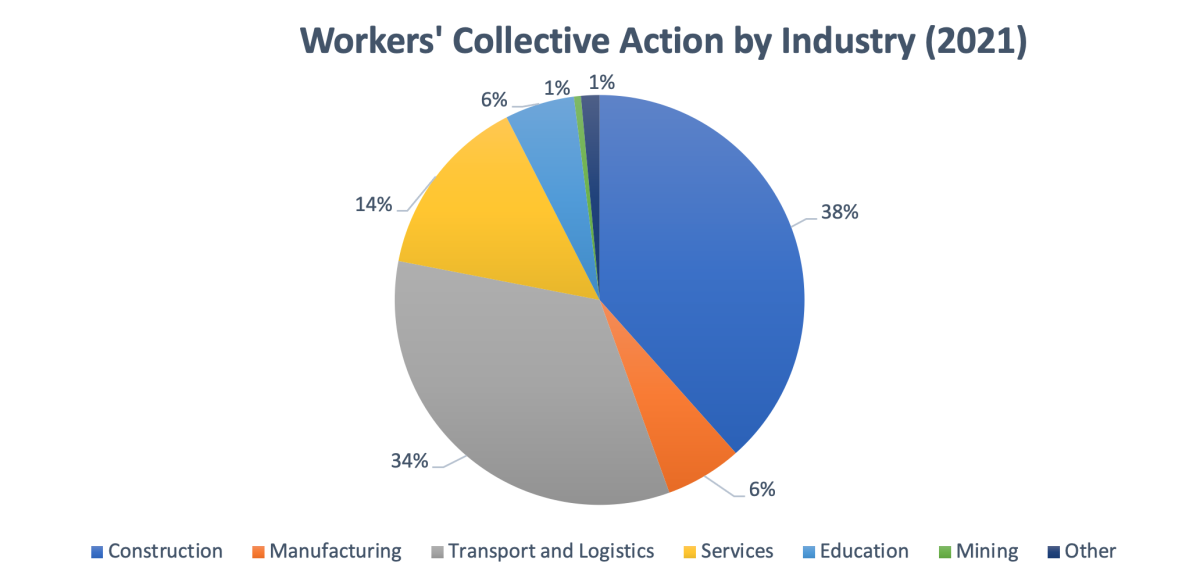

The largest proportion of strikes involve construction workers (38 per cent), though there is an overall decrease in the proportion compared to the year prior (45 per cent). Out of 118 construction sector strikes in 2021, 72 involve shopping mall construction projects.

Evergrande made headlines for unpaid wages last year. The Strike Map recorded workers at 11 Evergrande construction sites who said that they had not been paid. These incidents happened in inland provinces like Hunan, Hubei, Guangxi and Yunnan. Workers were driven to strike because of unpaid salaries, social insurance, and housing funds; and misappropriation of government funds.

The number of strikes involving interior decor and infrastructure workers decreased. This may be due to infrastructure investment rising by just 0.9 per cent over the year. Investment in real estate - residential, office and commercial premises - grew by 7 per cent.

Manufacturing, once a hotspot for worker strikes, saw collective actions fall to a new low of 66 incidents in 2021. Since 2015 and 2016, strikes protesting relocations and factory closures by large companies have been rapidly falling in number. Now, most strikes happen over wages and occur in small or medium-sized factories, which have been facing reduced orders and higher production costs. This is just one factor relevant to Henan province overtaking Guangdong province in total number of collective actions in 2021, with 108 total in Henan compared to Guangdong’s 92.

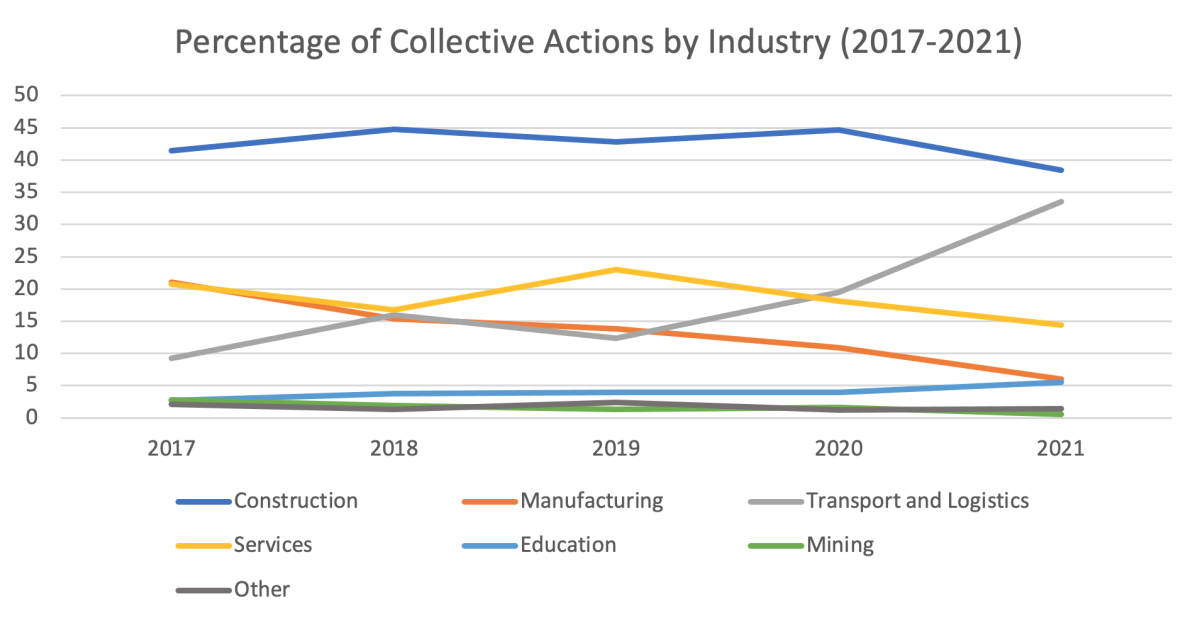

Looking at trends over the past five years, the proportion of strikes involving workers in manufacturing fell to 5 per cent in 2021, from 20 per cent in 2017. However, the proportion of strikes involving service sector workers has remained relatively steady at 15 to 20 per cent during this time. Strikes in the transport sector rose from 10 per cent in 2017 to 35 per cent in 2021.

We expect that the logistics and service sectors will continue to be the sectors to have the fiercest competition in 2022, resulting in regular boom and bust of small and medium enterprises, as well as protests over workers’ unpaid wages. Yet in the manufacturing and mining sectors, automation and technological developments have changed the nature of labour relations and have threatened the livelihoods of workers in those sectors, raising the potential for worker actions in these still-declining sectors.

We also note that government intervention in strikes and labour negotiations has increased to around half of all incidents last year. The police were dispatched to intervene in just 7.8 per cent of actions, or 85 incidents. The cases in which trade unions become involved still remains very low. Since 2015, Xi Jinping has spoken about the need to reform the official trade union to become more representative of workers’ interests. In 2021, he emphasised the principle of “common prosperity” for all. As we see from our data, workers’ voices are strong and loud, but without active participation from trade unions, the nation’s goals may be hard to achieve.