Construction workers see minor improvements in work safety and job security but grievances remain

14 April 2021The construction sector has long been China’s most dangerous industry. Although there have been some improvements in work safety and job security over the past several years, many workers are still at risk of life-threatening accidents and occupational illness, and they often lack basic protections.

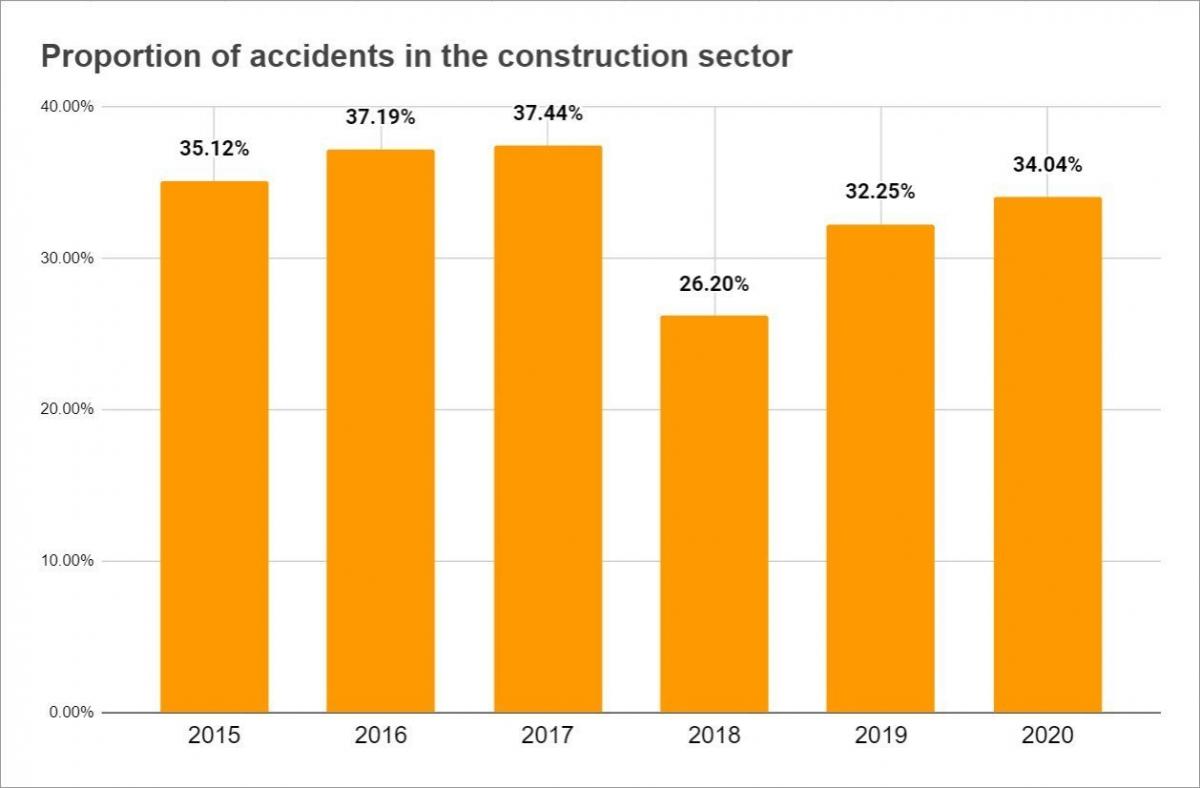

China Labour Bulletin’s Work Accident Map shows that in every year since 2015, it is the construction industry that has recorded the highest proportion of accidents of any sector, ranging from 26 percent to 37 percent of the overall yearly totals.

In just the last few weeks, the Work Accident Map recorded three separate fatal accidents in Tianjin in the space of five days, and several serious accidents at construction sites in other major cities such as Beijing, Kunming, Zhengzhou, Xiamen and Hangzhou.

China is pushing ahead with massive new infrastructure development projects to bolster the post-pandemic economy. Will the country’s more than 50 million construction workers reap the benefits of technological improvements and enhanced safety regulations? Or will they be even more at risk of accidents and illness as production ramps up again and the bosses push workers to complete their tasks in the shortest possible time?

CLB talked to three construction workers in different parts of the country about their wages and working conditions, and in particular recent efforts to reduce exposure to dust on construction sites. Dust inhalation has for decades been a major hazard on construction sites and has led to millions of workers contracting the deadly lung disease pneumoconiosis.

The workers reported that over the past two to three years, construction sites across the country have installed spray and dust prevention equipment. However, this is likely motivated by keeping local pollution levels under control rather than concern for worker safety. The key performance indicators of local officials are now directly linked to pollution levels.

Sites in larger cities have equipment for monitoring air quality that automatically adjust the amount of water sprayed according to the PM2.5 concentration in the air. But in small counties, spray equipment is installed for display only. Dust-proof cloths and plastic covers prevent dust from leaking out of the site, but workers inside still breathe it in.

Li, a construction worker from Shiyan, Hubei, works on a project in the port city of Qingdao, where he is responsible for water pipes and electricity. He lives with other workers in a prefabricated hut.

Each day at work, Li walks past notices at the entrance to his construction site proclaiming the protection of migrant worker rights and stricter work safety measures. Still, bosses don’t provide masks that guard against dust, and Li buys his own blue and white medical mask. He said he would immediately change jobs if he had serious breathing issues. “I won’t do that work,” said Li. “Someone I knew did it for ten years and suddenly died. He took a lot of protective measures but they didn’t work. You still breathe it in, and your nostrils are full of dust.” Those workers take home a salary three times that of Li’s, but he doesn’t think it’s worth it.

For jobs that aren’t too heavy, Li wears cheap gloves, which sell for just one yuan, though he knows they’re of poor quality. For dangerous jobs, like making iron pipes and working with cutting machines or glue with corrosive properties, he uses leather gloves. “Some colleagues are still reluctant to spend money to buy these, and they work without them,” he said.

Back in his hometown of Shiyan, Hubei, Li said he could expect take-home pay of 280 yuan per day, but working away from home he can earn 380 yuan per day, which includes 30 yuan for living expenses. Ultimately, a higher salary is what is most important to him because he now has a family to support. Some jobs pay less than 300 yuan per day but he won’t do them if the boss doesn’t take care of living expenses.

For Li, the size of water pipes can mean everything because the bigger pipes take more work and require more rest, and that means less pay. He’s encountered bosses who play favourites, like one in Wuhan who gave the lighter work of making small pipes to workers he knew, leaving the heavier work to those he didn’t. “It’s tiring to make larger pipes. After doing it for five or six days, you have to rest,” Li said. Since workers are paid per day, he earns more if he works with minimal rest.

Li did not sign a labour contract for the project that he is on now. The boss is from his hometown and “we all knew each other well,” he said. If a boss refuses to pay up, which has happened to him before, he calls them and records the call. He’s got in contact with trade unions, and they’ve told him he needs to collect evidence. Previously he has posted to social media the names of businesses who don’t pay their workers . After one post got 300 shares, the company paid up. Fewer bosses refuse to pay salaries nowadays, said Li.

He thinks that there’s still room to improve when it comes to work safety. Just a few days ago, he worked on a high-rise construction project in winds so strong he could barely open his eyes, and the work elevators shook and swayed. His boss wanted to meet a deadline, he said, and so ignored the danger.

Li considers construction work unstable because projects are short-term, so he must continually search for the next one. “This is what the living environment is like now,” he said. “We don’t make much, and every day I feel I have no money. I don’t have enough money in my pocket. I’m under a lot of pressure.”

Wang, a construction worker from Henan, is currently working in Zhoukou, in the same province. He is responsible for gas, bricks, moulds, and whitewashing walls. He says working conditions have improved and that he uses higher quality tools these days. Exposure to dust is not a major concern for him, and he doesn’t know anyone close to him who has fallen ill from pneumoconiosis.

In 2008, Wang received 200 yuan plus two meals per day, and now he makes around 300 yuan per day. This adds up to 5,000 yuan per month on average. Everything is based on oral agreements rather than written contracts.

If he could change one thing about the industry, it would be wage security. “I work hard but am not paid all the time,” he said. Wang finds that bosses are generally unreliable and getting paid is difficult. “I am still owed money for work I did more than ten years ago,” he said. It was only last year that he managed to get paid the 20,000 yuan he was owed for a job finished six years ago. He had to go to the transport department, housing construction department, the courts, and the trade union.

However, he has seen fewer instances of wage arrears compared to previous years, which he attributes to central government regulations to protect migrant workers. If he weren’t a construction worker, he said he’d like to raise chickens on a farm.

Ye, a construction manager from Henan, is in a better position than Li and Wang. He’s been in the industry for six years and usually works on projects that last half a year. Ordinary workers get paid 6,000 yuan a month, but as a manager he’s paid 10,000 yuan. He is currently working on a “rural beautification” project in Zhaoqing, Guangdong that involves sewage treatment and road construction.

He starts each day with an education session, telling his crew about safety measures. He said that since the work doesn’t involve digging or working underground, there is no need for respirators and workers just wear masks to protect against Covid-19. “There’s no dust in the countryside,” said Ye.

For Ye, work security is “much better than before.” He puts it down to salaries being paid on a monthly basis rather than on a project basis, a change that began in 2019. In the past, when he’s encountered bosses who don’t pay up, he finds posting on social media most effective. Ye is already in his 50s and plans to stop working in two to three years, when he will return to his hometown. He said, “I’m this age now, and I can’t go into anything else.”

As these worker accounts of recent changes in the construction industry show, worker protections are limited and work conditions largely depend on individual bosses. Without the required labour contracts, workers have to go to great efforts to document and prove that they are owed wages, which can take years of fighting within the bureaucracy. In light of China’s new infrastructure boom, workers in the construction industry would benefit from coordinated representation for these problems common at sites across the country.