Food delivery worker activist accused of “picking quarrels”

25 March 2021Food delivery worker, Chen Guojiang has been accused of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (寻衅滋事), the catch-all charge used by the authorities to crackdown on activists, according to reports from a labour concern group.

Chen, who sought fair pay and greater worker protections for fellow delivery drivers, was finally allowed to see his lawyer on 24 March, nearly a month after he was detained on 25 February. His lawyer reported that Chen was in good spirits.

On 15 March, Chen's father had posted an open letter and crowdfunding request to WeChat. In it, he said that he had not yet received a detention notice as to the reason for his son’s arrest. China’s Criminal Procedure Law (Article 43) stipulates that families should be notified within 24 hours.

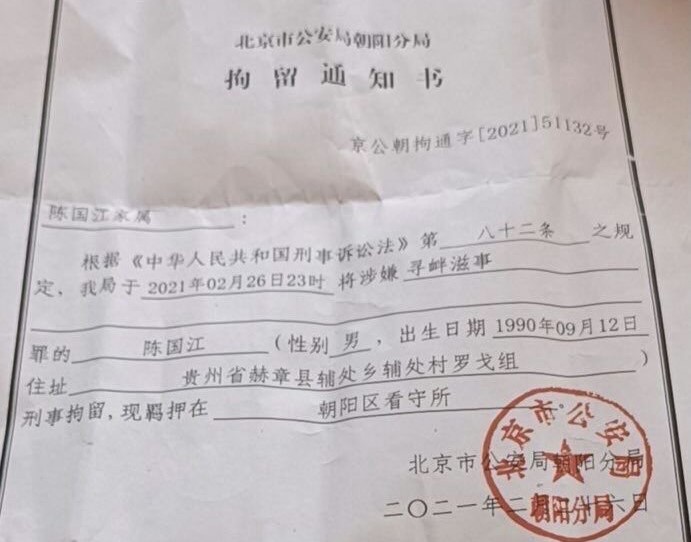

The following day, Beijing’s Chaoyang district public security bureau sent the family a notice informing them of the charge and confirming that Chen was being held at the district’s detention centre. See photo from工號 51 below.

Chen’s father had hoped that he could raise 50,000 yuan for lawyers’ fees. And even though WeChat’s censors blocked his post in about one hour and issued a pop-up warning that the transaction contained a “fraud risk” the family still raised 120,000 yuan within ten hours. The following day Chen’s sister asked for donations to stop.

Chen’s fellow delivery workers are demanding his release. A picture of a delivery driver holding a notice on which is written “release the leader,” a reference to his online handle “Leader of the Drivers’ Alliance” (外送骑士联盟盟主), has circulated on social media.

As an advocate for delivery workers’ rights, Chen posted videos which called out platforms for oppressing workers and violating laws and regulations by fining drivers for late deliveries. He has also pointed the finger at government departments for passing the buck on regulating the gig economy.

Chen said that he managed 16 WeChat groups reaching over 14,000 delivery driver contacts. He called for drivers to stop work when faced with unfair working conditions. In an interview with Initium published last month, he said that since wages have declined, drivers endanger their own safety to fulfil more orders and maintain their income.

China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map records that strikes involving delivery drivers, mainly over wage cuts, increased to 45 in 2019, up from 10 in 2018. The Work Accident Map also shows that in 2018, 121 drivers were involved in road accidents, in which 19 died. Although protests by food delivery workers declined significantly last year because of the pandemic and a massive influx of new drivers into the industry, there are now signs that frustrated workers have returned to collective action.

On 1 March, delivery drivers for online platform Meituan went on strike to protest a decrease in delivery wages in at least two cities, Shenzhen and Tongxiang in Zhejiang. There was another strike reported the following day by Meituan drivers in Linyi, Shandong. On 8 March, Ele.me customers took to Weibo to complain about slow or non-existent deliveries, which suggests that more workers were on strike, although it is difficult to confirm this due to sensitivity over reports of social unrest during the ongoing National People’s Congress.

Food deliveries have become ever more crucial since the pandemic as people under lockdown relied on the industry to keep them supplied. While the industry has boomed, its profits have not been fairly distributed to the backbone of its workforce.

This year, Ele.me promised drivers bonuses for working over the Lunar New Year holiday period if they reached delivery targets. A video released by Chen last month revealed that drivers found these targets impossible to meet due to the low numbers of orders allocated to them by the platform. In one week, drivers were expected to deliver 380 orders. Customers left comments on the video saying that they paid delivery fees over four times the usual for orders during this period.

Ele.me issued a public statement on its Weibo account promising to retrospectively adjust these targets so that more drivers could receive bonuses. The company faced a social media backlash last year when it offered the family of a driver who died on the job just 2,000 yuan in compensation.

In September last year, Chen expressed the hope that the authorities could take the lead in setting up a union-like organization for drivers that could negotiate with the platforms on behalf of workers and allow local government departments set the standards for the industry, rather than arbitrary pronouncements from private companies like Meituan and Ele.me.

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions has included food delivery workers in its list of Eight Key Sectors that are now said to be the union’s priority. So far, however, the union has done little to help its new members other than provide skills training, legal assistance and some medical benefits. Nothing has been done to challenge the power monopoly currently held by the food delivery companies.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on 9 March 2021.