Bangalore garment workers fight for basic rights as production resumes after lockdown

18 June 2020When India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a nationwide lockdown to combat the Covid-19 pandemic on 24 March, very little thought or consideration was given to the country’s rural migrant workers, most of whom had no option but to walk home to their villages and wait for the crisis to pass.

Despite widespread condemnation of this callous treatment, many workers found themselves in exactly the same predicament when pandemic restrictions started to be relaxed and factories resumed production.

About 150 women who were employed at Arvind Mills in Bangalore, for example, were told they would have to walk the 150 kilometres back to work or quit their jobs. Arvind Mills is India’s largest denim maker, supplying major international brands such as H&M, The Gap, Levi’s and others. More than 1,000 garment workers are employed at its factory located in the Mysore Road area of southwest Bangalore. The factory was forced to close throughout the whole of April, leaving workers with no pay for more than a month.

The company had previously provided its own buses to transport workers from outlying villages, but when production resumed in May, it cancelled this service and started recruiting workers living nearby the factory to replace those workers who could not arrange their own transport from the villages.

The Arvind workers were not alone. In a survey of 82 garment workers in Bangalore, Ramanagara, Mandya and Mysore districts, 63 percent of the respondents had not received their April salary and the only way for them to get paid was to make their own travel arrangements to the factory. This was despite government orders that wages should be paid in full during the lockdown.

Under increasing financial pressure, the Arvind workers sought help from the Karnataka Garment Workers Union (KOOGU/KGWU) in getting the wages owed to them. KOOGU launched a series of petitions, protests and negotiations, which eventually led to a partial resolution of the workers' demands.

KOOGU first sent a complaint letter to the Karnataka Labour Department and contacted civil society labour organizations on social media to spread the news. Then, on Saturday 6 June, the workers staged a sit-in outside the Arvind factory. One protestor said Arvind had already started recruiting their replacements. “What are we supposed to do? We cannot keep begging for food from our neighbours every other day… They told me that Arvind is a great factory and that we should not worry. They promised to take full responsibility and make all necessary arrangements [during the pandemic].”

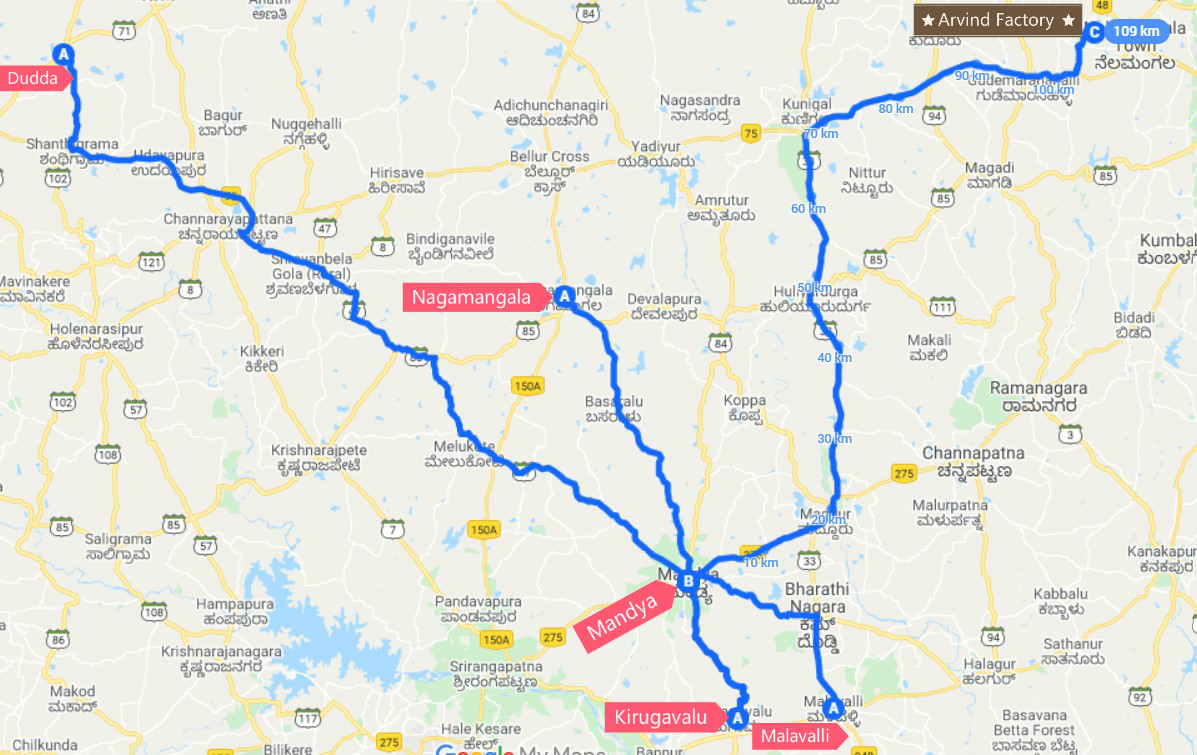

In response, Pramila Naidu, the head of the Karnataka State Commission for Women (KSCW), visited the protest site on the same day and talked to the workers. With the help of the KSCW, the workers drafted an appeal to management and successfully negotiated a deal over the weekend whereby the workers would receive 50 percent of their wages during the two-month lockdown plus bus passes to and from the various villages in Mandya District to the factory (see map below).

Point B is the main bus terminal in Mandya. Points A are the workers’ villages from which they travel from to get the factory bus.

However, it was a short-lived victory. When they tried to use their new bus passes at 6.00.am on Monday morning, the workers discovered that — because the bus company wanted to minimize losses and increase the number of paying customers — only two workers could board the bus at any one station.

Previously, all the workers could easily make it to the factory in time for breakfast before work, but now the journey would take much longer or could not be completed at all.

KOOGU has vowed to keep applying pressure on Arvind to force management to reinstate the company bus service for all workers.

The Arvind workers’ struggle comes at a time when many state governments are rolling back labour protections in a bid to prop up businesses and restart the economy. In May, Uttar Pradesh took the lead in exempting industries from the majority of labour laws for 1,000 days. Since then, nearly ten other states including Karnataka have introduced labour law revisions or exemption policies. Karnataka announced on 22 May that all labour regulations would not apply for the next three months. Although this announcement has not been fully implemented, it could still hamper the workers’ struggle. But the women of Arvind and their trade union representatives say they are determined to continue the fight.

This article is part of an occasional series commissioned by CLB designed to foster worker solidarity in the global south.