How Guangdong missed the chance for genuine workplace collective bargaining

15 October 2019During the early 2010s, there were hopes that the Guangdong provincial government would introduce legislation that provided employees and employers with a framework to resolve labour disputes through genuine collective bargaining and thereby reduce the rapidly growing number of strikes and protests in factories across the province.

However, the business lobby waged a vociferous campaign against the draft legislation and by the time Guangdong finally introduced its Regulations on Collective Contracts in Enterprises (广东省企业集体合同条例) in September 2014, the law was so watered-down as to be effectively useless.

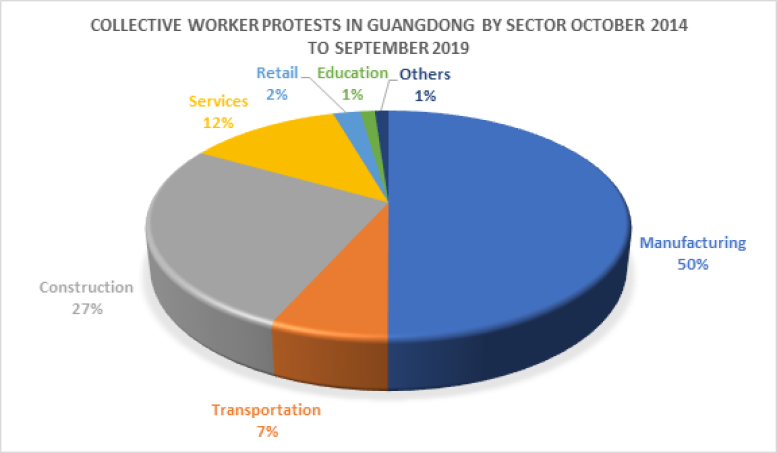

Denied the opportunity to engage in peaceful collective bargaining, workers had no option but to continue to take collective action. In the five years since the regulations went into effect, there have been 1,279 collective worker protests in Guangdong alone, accounting for 12.7 percent of all the incidents recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in that period. Crucially, of these 1,279 incidents, only 37 involved some form of negotiations between labour and management, while local government officials mediated in 84 cases. By contrast, police intervened in 416 cases and made arrests in 97 of them.

Unlike most provinces where disputes involving construction workers, as well as workers in transport and services, tend to dominate, around half (639) of all protests in Guangdong were in the manufacturing sector, the key sector that the Collective Contract Regulations were supposed to focus on.

The regulations were designed to allow factory workers to negotiate pay increases with management however pay increases were not the main concern of Guangdong factory workers in this period. The main issue for factory workers was simply getting paid or being laid off without any pay or compensation as factory owners continued to head for the exits. Specifically, there were 445 cases of collective labour disputes at factories related to wage arrears and in 160 disputes stemming from factory closures in Guangdong recorded on the Strike Map in the last five years. In contrast, there were just 68 cases of workers demanding a wage increase.

During this ongoing labour unrest, the Guangdong Provincial Federation of Trade Unions claims it had been busy organizing workers and negotiating collective contracts with employers. By the end of 2018, the provincial trade union claimed that 30 million out of Guangdong’s 32 million workers were members of the union and that union branches had been established in 749,000 enterprises. The union said it had signed 164,000 collective contracts covering 464,000 enterprises at the end of 2018, and would continue to strive for an effective labour/management bargaining system over the next three years. More than 80 percent of enterprises with a union had already established such a system, and more than 90 percent of enterprise employees were aware that they had a collective contract, with a satisfaction rate of more than 60 percent, the union said.

However, CLB’s research suggests that the union is still far removed the day to day struggles of workers in Guangdong. In our survey of Guangdong trade union officials’ response to seven labour disputes that occurred in the province during August 2018, there was trade union involvement in just one case. In discussing that dispute at the Hong Kong-owned Nanling Toy Factory in Shenzhen, local union officials in Longgang district conceded that although the factory had been in Shenzhen for nearly three decades and employed more than 4,000 workers at its peak, the local union only got around to organizing the enterprise when it was about to close down for good in 2018.

Moreover, the other local officials interviewed in Guangdong conceded that most of the enterprise trade unions that had been established were under the control of management and that workers have no real input in negotiations over wages and working conditions. As far as we can tell, there has only been one recent example of factory workers in Guangdong asking to set up an enterprise trade union. That was the famous dispute at the Jasic Technology factory in Shenzhen in July 2018, which led to a wave of arrests of workers, activists and their supporters during the second half of the year

The Guangdong Collective Contracts Regulations did in theory empower enterprise trade unions to collectively bargain with management but because most enterprise unions were under the sway of management and had no legitimacy with the workforce, they could not be effective bargaining representatives. The only real collective bargaining to occur during this time was initiated by the workers themselves, usually following wildcat strikes that forced the employer to the bargaining table. These bargaining sessions occurred organically, outside the framework of the regulations, and were often based on the experience that civil society labour organizations in the province had built up over the previous five years. Civil society groups were involved in well over one hundred bargaining cases and, in 2013, even developed a handbook for collective bargaining which could have widely adopted if the government and trade union had got onboard. Unfortunately, a sustained government crackdown on these civil society organizations in late 2015 meant that the impetus for grassroots organizing was largely lost.

Four years later, the provincial and local trade unions are still scrambling to make a real and beneficial impact on labour relations. Moreover, their problems have been exacerbated by China’s economic slowdown and the trade war with the United States which has disproportionally impacted export-orientated manufacturers in Guangdong. The union is trying to resolve labour disputes through established legal channels such as labour arbitration. To this end, the union set up a 12351 hotline for workers’ grievances and received more than 91,000 complaints in one year. A lot of these cases are dealt with individually rather than collectively, a process that takes a lot of time and does not really address the fundamental causes of the dispute.

While legal assistance can be helpful in addressing violations of labour rights, the advantage of collective bargaining is that it creates a mechanism whereby workers can ensure their rights and interests are protected in a mutually acceptable and legally binding collective contract. This also importantly helps to prevent employers from taking unilateral action that violates labour rights in the first place.

Despite missing the collective bargaining boat in the early 2010s, there is still a chance that during the ongoing process of trade union reform, the Guangdong union will start to re-evaluate its role and begin the process of transforming itself into a genuine advocate for and a representative of labour.