The shifting patterns of labour protests in China present a challenge to the union

09 July 2019Collective protests by China’s workers are typically small-scale, spontaneous actions designed both to expose and resist employer abuses and violations of basic labour rights such as the non-payment of wages.

The large-scale strikes and protests by factory workers that highlighted labour activism five years ago, are becoming less and less visible today. Labour activism is now far more fluid and transitory and as such presents new challenges to both grassroots organizers and China’s official trade union.

Around 95 percent of the 712 collective protests recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in the first half of 2019 involved less than 100 workers, and were predominately in the construction industry, services and transport. There were no protests with more than 1,000 workers during the first half of the year. During the same period in 2014, however, the Strike Map recorded 49 protests with in excess of 1,000 workers, 37 of which were in the manufacturing sector, including the massive Yue Yuen shoe factory strike in April 2014 when 40,000 workers staged a two week protest over social insurance and low pay.

This dramatic fall in the number of large-scale actions is partly explained by the decline and consolidation of manufacturing in China that has resulted in the remaining large-scale factories generally offering acceptable pay and working conditions. It also indicates the determination of the authorities under Xi Jinping to pre-empt large-scale protests that might threaten social stability China.

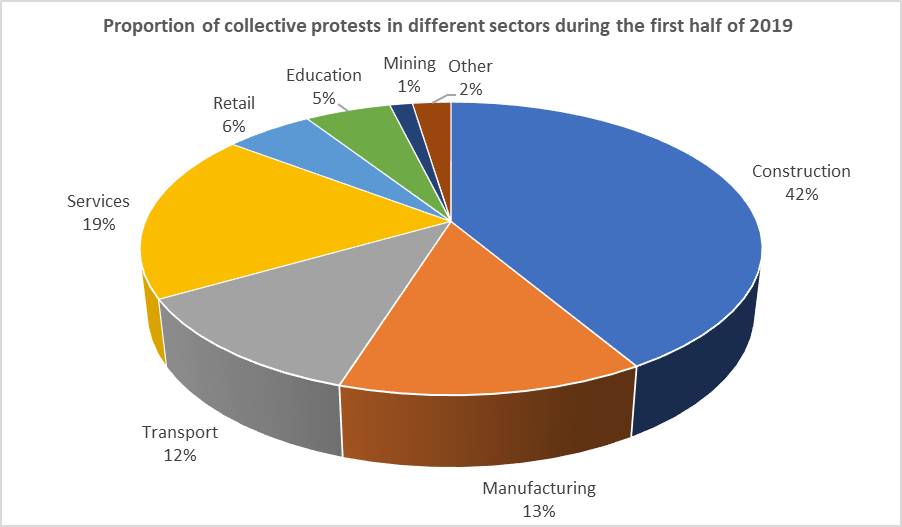

In the first half of 2019, the Strike Map recorded a total of 95 strikes and protests by factory workers, just 13 percent of the overall total. This was actually about the same level as during the first half of 2018, suggesting that the Sino-US trade war has so far had a limited impact on factory worker protests, except perhaps in the manufacturing export centre of Guangdong, where there has been a slight increase in worker activism over the last year.

As noted in our analysis of the state of labour relations in 2018, the vast majority of labour disputes in China now occur in domestically-owned private enterprises. Out of the 601 incidents recorded during the first half of 2019, in which company ownership could be verified, 80 percent were in domestically-owned private enterprises, 15 percent occurred in state-owned enterprises, with only about two percent in wholly-owned foreign/Hong Kong/Taiwan ventures.

By far the largest growth in worker protests occurred in the service and retail sectors, which when combined accounted for one quarter of all protests in the first half of 2019, up from 14 percent in the first half of last year. Many of these protests occurred in major urban centres (12 in Beijing, and seven each in Shanghai and Shenzhen) and featured a vast array of professions; street cleaners, investment consultants and accountants, medical workers, hotel and restaurant workers, sales agents, gym and beauty salon employees, as well as workers in the traditional retail and e-commerce sectors. Workers in the service sector are among the lowest paid in China and many have to fight for every cent they earn. A group of 100 sanitation workers in Henan who went out on strike on 23 April, for example, earned just 1,450 yuan a month.

Workers in the retail sector accounted for six percent of all collective protests recorded in the first half of 2019. Veteran supermarket employees who are most at risk of being laid off were some of the most active protestors.

Taxi drivers, food delivery workers and couriers continued to stage regular strikes and protests over low pay, excessive management fees, high fuel costs, ineffective government regulation and company bankruptcies. Following the collapse of well-known courier, Rufengda Express (如风达快递), for example, workers staged a series of protests in Beijing, Shanghai and Xi’an. More than one third of the collective protests by transport workers included demands for higher pay. Many workers complained that they are continually squeezed by the online platforms that now dominate the transport and logistics industry in China. The two main food delivery companies , for example, reduced rates soon after the Chinese New Year, leading to a surge in protests by drivers across the country.

Generally, however, worker protests in China are related to the non-payment of wages rather than overt demands for higher pay. Wage arrears were a factor in 80 percent of the incidents recorded on the Strike Map in the first half of the year. In the construction industry, which accounted for 42 percent of all protests, that proportion went up to a staggering 99 percent. As CLB pointed out in our research report on the construction industry in China published this year, wage arrears has been an endemic problem for decades and, despite countless efforts from all levels to government to eradicate the problem, it remains thoroughly entrenched in the industry today. Administrative and government intervention has done little to help construction workers, while the official trade union has remained inactive on the side lines.

There is clearly an urgent need for the trade union to get more actively involved in organizing construction workers and negotiate collective agreements that can guarantee the payment of decent wages on time for all employees from day labours to senior engineers. Neither can the union afford to ignore the millions of workers in small, privately-run companies in the service sector and transport industries that have emerged as a major source of labour unrest. There is evidence that some trade union officials do recognise this need but clearly much more has to be done.