#MeToo: Send letters to your legislators, Chinese activists urge

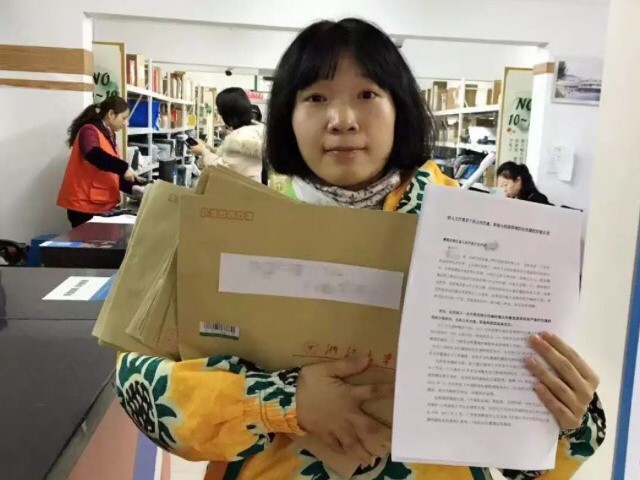

16 January 2019Gender equality activists in China are calling on people from all over the country to send letters to legislators in Beijing calling for a new law against sexual harassment.

“People from across the whole country who wish to establish a national mechanism to fight sexual harassment should start sending letters to your legislators,” urges an article by the WeChat account @genderequality. The campaign is timed to coincide with the upcoming National People’s Congress, which takes place in March each year.

The #MeToo movement in China has encouraged many victims to speak up, particularly in 2018, when lawyers, journalists, feminists and activists worked together to expose sexual harassment cases against powerful men in media, civil society and academia. However, the activists organising the current letter-sending campaign argue that a national legal framework to define, prevent and sanction sexual harassment in the workplace, in public transport and in academic institutions, is still lacking.

In its sample letter to legislators, @genderequality points out that in the past few years there have been some encouraging improvements to China’s legal system. For example:

- In 2005, the term “sexual harassment” was included for the first time in an amendment to the Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests. Article 40 of the amended law stipulates that “Sexual harassment against women is a violation of law, (women) victims have the right to file their case in the workplace and with relevant authorities.”

- In 2011, Article 11 of the Outline for the Development of Women highlighted that “a comprehensive legal and administrative mechanism to prevent and stop sexual harassment will be established to strengthen the fight against sexual harassment practices.”

- In 2012, the Special Rules on the Labour Protection of Female Employees stipulated in Article 11 that “Employers have to prevent and stop sexual harassment against female staff at the workplace.”

The common characteristic shared by these legislative efforts however is the lack of a clear definition of what actually constitutes sexual harassment. This means that many lawsuits are dismissed by the courts if the victim comes forward. The current campaign seeks to bring this deficiency in China’s civil and penal legal frameworks to the attention of legislators.

“The #MeToo movement has helped more and more victims of sexual harassment to step forward and tell their story,” argues @genderequality, but then stresses that “a national mechanism to fight sexual harassment has not yet been established,” which in the end results in “victims being left defenceless and perpetrators unpunished.”

With regard to the specifics on how to deal with sexual harassment cases at the workplace, the sample letter to legislators stresses the importance of defining and classifying sexual harassment, and conduct trainings to increase general awareness as well as encouraging staff to come forward if they believe they have been subject to sexual harassment. The letter also emphasises the importance of establishing clear procedures for filing complaints which simultaneously protect the victim from retaliation and stipulate processing timeframes, as well as punishment for the perpetrator including but not limited to suspension of duty.

In spite of intensified online censorship, discussion of sexual harassment and gender inequality in China remains a hot topic. The reason is simple: the sheer volume of cases accumulated through the years pushes victims of workplace gender discrimination and sexual harassment, who have no other avenue for redress, to voice their complaints on social media.

A recent research report estimates that as much as 15 percent of urban women in China aged between 20 to 64-years-old have been sexually harassed at some point in their lives. The proportion of victims surges to 70 percent when looking at the particular demographic group of migrant women factory workers, according to a 2013 study conducted in Guangdong.

The @genderequality article concludes on a personal note:

Sexual harassment is common at the workplace, academic institutions and public transportation; I am a victim of sexual harassment, as such I have suffered the sense of powerlessness when seeking support for my case. I am deeply aware of the strong gender discrimination and gender oppression behind this social phenomenon.