Identifying the trends in workers’ collective action 2015-17

19 September 2018In this English-language extract from CLB’s new report on the workers’ movement in China (中国工人运动观察报告2015-2017) we look at more aspects of the collective action taken by Chinese workers between 2015 and 2017, specifically; the transition away from spontaneous, emotional protest towards rational, organized collective action, the diversification of actors and development of strategies in collective protests, as well as the broader distribution of protests.

For the Chinese original please see pages 11 to 16 of the report under the heading 工人集体行动的特点与趋势. See also, the earlier English-language extract discussing the proliferation of online organising tools used by China’s workers.

Striking workers at Nanhai Honda confront the local trade union. Photograph Booby Yip, Reuters, May 2010

A more comprehensive understanding of collective action

By a more comprehensive understanding of collective action we mean that, while taking collective action, workers have moved from an emotional to a rational attitude, and from a spontaneous to a more organised approach.

In the 6,694 cases recorded on CLB’s Strike Map during the period of this report, and in particular the ones involving a higher number of participants, we noticed the following trends: 1) these collective actions have a clear leadership structure, 2) they have elected worker representatives, 3) there was no destruction of company property, 4) workers acted collectively in escalating and deescalating the dispute in an orderly fashion, 5) workers stressed the resolution of disputes through collective bargaining.

To illustrate this more comprehensive understanding of collective action we can examine the differences between the 2010 Nanhai Honda case and the 2015 Lide Shoe Factory case below:

In 2010, workers at the Foshan Nanhai Honda auto parts factory staged a strike seen by many observers as a “a defining case in the history of China’s labour relations.” The strike lasted for almost 20 days and was led by a group of 17 workers, who maintained a high morale in the process. However, the prevailing mood throughout the dispute could be described in two words: fear and anger. The “collective action” was in fact initiated by a series of individual strikes, and as time went on and as management’s attitude became harsher (forced resumption of work, dismissal of a dozen workers who were leading the strike), the cohesiveness of the collective action started to show cracks. Workers did not know how to respond, and when management presented counter proposals, workers became incoherent and divided. In the end, civil society organisations played the role of facilitator/negotiator between management and workers, finally achieving a mutual agreement for a salary increase and the resumption of work. In retrospect, Honda workers did not do the necessary preliminary organizing work to sustain effective strike action and one could argue that it only lasted as long as it did because of the pent-up frustrations and anger of workers towards management.

Five years later, in 2015, workers at Lide Shoe factory in Guangzhou’s Panyu district went on strike demanding compensation for factory relocation. During this collective action, workers exhibited more rational and orderly behaviour. In over four months of collective action split into two stages, the workers maintained a calm and self-restrained attitude. During both the strike action and factory occupation, workers never damaged company property nor took to the streets in protest. Before taking collective action, workers had completed a multi-layered democratic process of organising, electing their representatives, establishing media liaison teams, a solidarity fund administrative team as well as a security team. This helped move collective action away from a unstructured, fragmented and chaotic amalgam into a unified, organised and action-ready state.

Diversification of actors in workers’ collective actions

Over the last three decades, China’s workers have experienced mass lay-offs during the reform of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the 1990s, the surge of privately-owned enterprises in the 2000s, and the decline of traditional labour-intensive manufacturing companies, the boom in new services sectors and increased informalisation of labour, etc. in the 2010s. Chinese workers no longer depend on the political establishment for their survival and hence have evolved from a largely passive attitude towards a more proactive defence of their labour rights. Among the cases covered by this report, one can notice the participation in collective actions of ex-SOE workers who have already lost their ‘iron bowls’ and workers still employed by SOEs, rural migrant workers employed in the private sector, staff in public institutions such as schools and hospitals and even civil servants. It is important to highlight the fact that when collective actions take place, public support from society at large is the norm rather than the exception, and often civil society actors such as lawyers, journalists and academics can be seen on site.

Evolution of workers’ collective actions

To outside observers, Chinese workers’ collective actions are manifested in strikes, factory occupations, blocking roads or protesting in front of a government buildings etc. However, the cases analysed in this report show that workers’ collective actions have been evolving through the years. Workers are increasingly seeking to resolve disputes through a combination of the actions described above as well as collective bargaining to achieve their demands. Granted, the 2010 Nanhai Honda dispute may have been resolved only with the participation of civil society actors taking the initiative to negotiate an agreement but this case nevertheless opened a new chapter of collective bargaining in China.

During the Lide Shoe factory dispute discussed above, workers went on strike, bargained with management, went on strike again to continue exerting pressure, and then sat at the bargaining table to achieve a mutually acceptable resolution. This is an exemplary case that illustrates how Chinese workers have developed a measured, rational and strategic approach to labour dispute resolution, taking China’s worker movement to the next level. This evolution of workers’ collective actions breaks the all-too-common vicious circle of strikes followed by management reprisals and local government’s use of police force to supress the protest, further aggravating workers’ disenfranchisement. The Chinese government has taken note of this fundamental difference between “mass incidents” (official euphemism to describe collective protests in China) and workers’ collective actions: the latter seeks resolution through negotiations and compromise rather than the simple venting of frustrations without clear goals. In this context, the Lide case is an important prototype in the development of China’s future collective bargaining system.

Proliferation of workers’ collective actions

During the period covered by this report, there has been a clear proliferation of workers’ collective actions both geographically and across different industrial sectors. Geographically, strikes and protests are spreading out of the coastal areas of the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta and into inland provinces. During this time frame, the central province of Henan saw the highest share of workers’ collective actions in the construction, transport and retail sectors. By contrast, Guangdong saw a decline of collective actions from 38 percent of the national total in 2013 to 11.8 percent in 2017.

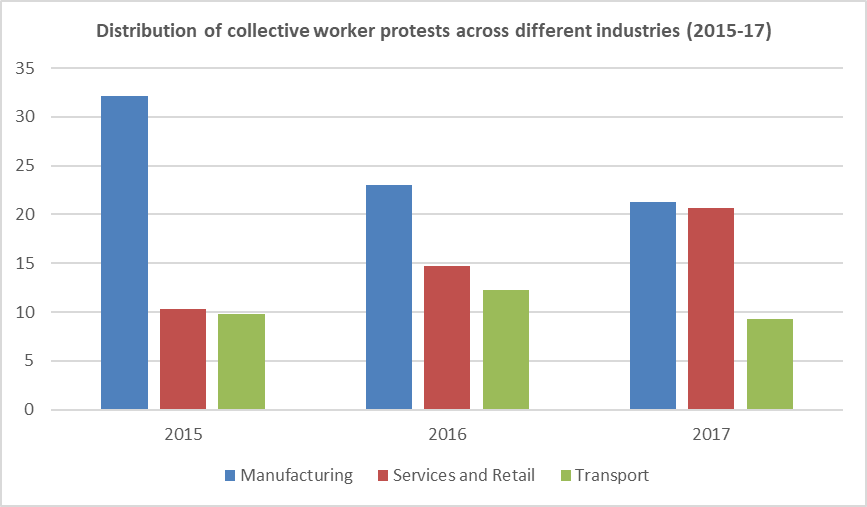

From the perspective of industrial sectors, workers’ collective actions in China have spilled out of traditional manufacturing into the relatively newly developed services and retail sector. According to the data collected, there has been a clear decline in the percentage of collective actions in the labour-intensive traditional manufacturing sector, reaching a record low of 21.3 percent in 2017. Simultaneously, there has been a gradual increase in the share of strikes and protests in the services and retail sector, reaching a record high of 20.7 percent in 2017. As more workers are absorbed into the services sector, the labour relations issues plaguing traditional manufacturing - lack of formal labour contracts, unreasonably low wages, insufficient social insurance and poor benefits- have moved along with them. The persistent and continual violations of workers’ rights have left workers with no option but to take collective action, the only difference now is that the protagonists are increasingly employed in the service industry.

While the spectrum of collective action by China’s workers has continued to broaden and diversify, there has been no contemporaneous development of a collective bargaining system to regulate the persistent imbalances in labour relations. This leaves Chinese workers with no choice but to take collective action in an attempt to recover their losses and demand a fairer share of profits. In the absence of both a voice to represent workers’ interests and a collective bargaining system to mitigate disputes, Chinese workers will not simply accept the status quo. Rather they will continue to take collective action until the day a collective bargaining system is firmly in place.