An analysis of collective protests by workers in different industries

22 August 2018In this English-language extract from CLB’s new report on the workers’ movement in China (中国工人运动观察报告2015-2017) we look at the collective actions of workers in different industries, examine ownership patterns and the response of the local authorities to labour unrest. For the Chinese original please see page 3 of the report under the heading 对工人集体行动的分行业观察, which includes more detailed statistics.

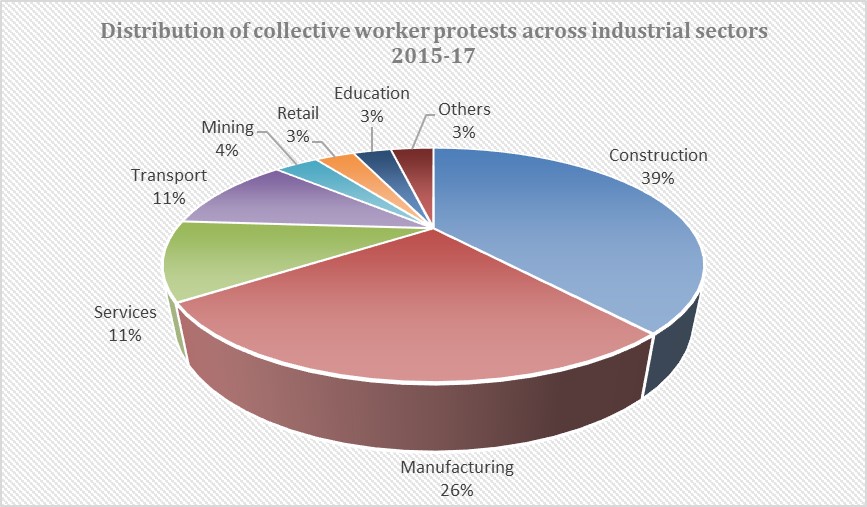

This analysis is based on the 6,694 cases of worker collective action recorded on CLB’s Strike Map from January 2015 to the end of December 2017. The Map broadly categorizes industries as construction, manufacturing, services, transportation, retail, education and mining. During this three-year period more than one third of all incidents involved construction workers, a quarter were in manufacturing, and transportation and services both accounted for 11 percent of the incidents. See chart below.

Construction

There were 2,595 construction worker protests recorded during this period, with the highest concentrations found in Henan, Guangdong, Shandong, Hebei and Sichuan. The vast majority of incidents occurred in residential and commercial building construction and repair projects, usually involving private companies, with a smaller number related to infrastructure projects funded by local governments.

More than 99 percent of all these cases involved demands for wages in arrears, confirming the persistent and ingrained nature of the wage arrears problem in the construction sector. Other demands included compensation for lay-offs and social insurance contributions. Collective protests typically involved demonstrations with workers holding banners demanding payment of wage arrears. Construction workers were more likely than workers in other industries to threaten suicide by jumping of high buildings etc. in pursuit of their demands, however police intervened in just 25 percent of construction worker protests and made arrests in four percent of cases, about the same as the overall average across all industries.

Manufacturing

There were 1,770 cases of factory worker protests with most occurring in the coastal manufacturing centres of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong and Zhejiang. Workers in the clothing, apparel and footwear industries accounted for 20 percent of the cases, followed by electronics (14.8 percent), heavy industry such as steel and aluminium (8.8 percent) and automotive and shipbuilding (5.8 percent).

The majority of incidents (1,003 in total) were in domestically-owned private enterprises, with state-owned and foreign-owned enterprises accounting for 131 and 122 incidents respectively. Once again, demands for wages in arrears was the most common demand occurring in 75.5 percent of cases, with demands for compensation and social insurance contributions occurring in 15.7 percent and 11.6 percent of cases respectively.

Strikes and collective protests by factory workers often involve greater numbers of protestors and as such are more likely to lead to police intervention and arrests. Police intervened in one third of all incidents and detained or arrested workers in 7.4 percent of cases.

Services

The Strike Map recorded 726 incidents, about 11 percent of the total, in service industries during this period. Worker protests were concentrated in the catering industry which accounted for 24.1 percent of cases, followed by the hospitality industry with 14.2 percent of cases. However, labour disputes now erupt in an increasingly broad range of service industries such as IT companies, banks and finance companies, medical facilities, leisure and sports facilities like gyms, golf courses and amusement parks, television stations and other local media outlets. The vast majority of enterprises (74 percent) in which labour disputes occurred were privately-owned domestic companies, while there were only four incidents in foreign-owned companies.

More than 82 percent of cases involved wage arrears, reflecting the instability of many businesses in the rapidly expanding service sector. Strikes and protests by service workers tended to be relatively small-scale and peaceful, rarely resulting in police interventions or arrests. It was not unusual however for local government officials to mediate or broker negotiations in these cases.

Transportation

There were 717 cases involving transport workers during this period. These cases had a much more even distribution pattern than many other industries indicating that the problems faced by transport workers are felt across the whole of China. Taxi drivers accounted for 63.2 percent of all protests, followed by bus drivers (and crews), couriers and ride-hailing app drivers. Private enterprises again accounted for most of the protests (71.8) reflecting the extent to which privatisation and intense competition has eroded working conditions in the transport industry.

The most common grievances of transport workers were unfair competition from unlicensed operators, and high management or vehicle rental fees for taxi drivers. Transport worker protests usually took the form of strikes and slow-speed processions but taxi drivers also used so-called “fishing expeditions” to provoke conflict with ride-hailing app drivers. However, these actions only rarely led to arrests.

Retail

There were 212 cases of collective worker protests in the retail industry, with Henan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan, Hebei and Guangdong having the highest concentrations of labour unrest. Most disputes occurred in shopping malls and department stores (22.6 percent) and supermarkets (19.3 percent) with the majority (74.5 percent) being privately owned concerns. However, 13.3 percent of cases were in foreign-owned or joint-ventures. Many global retailers such as Walmart have established operations in cities across the whole of China and these outlets are just as likely to see worker protests as domestic companies. See our research report China’s Walmart workers: Creating an opportunity for genuine trade unionism for more details.

Demands for wage arrears again dominated the workers’ list of grievances but protests against lay-offs were also very common. Intense competition among retailers and the growing pressure from e-commerce led to many retail outlets suddenly closing down leaving workers out of a job and out of pocket. As in the rest of the service sector, collective protests tended to be relatively small scale and rarely attracted the interest of local authorities.

Mining

There were 235 collective protests by miners, concentrated largely in the traditional mining areas of Shanxi, Shaanxi, Hebei, Shandong and Henan. The vast majority of incidents (93.6 percent) occurred in the coal mining industry, with an even distribution between state and privately-owned mines, in those cases where ownership could be determined.

The vast majority of protests were over wage arrears, which became a chronic problem in China as the coal industry contracted during the period covered by the report. Perhaps the best-known collective action occurred in the Spring of 2016 when thousands of angry coal miners in the north-eastern city of Shuangyashan staged a series of mass protests that forced the local government to pay months of wage arrears owed by their employer, the state-owned Longmay Group. Despite the sometimes-confrontational nature of these protests, workers were arrested in just 5.1 percent of cases, suggesting perhaps that the authorities did not want to provoke further protests with mass arrests of state-owned enterprise employees.

Education

There were 206 collective protests by teachers and education workers during this period, clustered predominately in Henan, Hebei, Jiangsu, Hubei and Hunan. A total of 160 (77.7 percent) occurred in secondary and primary schools, with 18 incidents in kindergartens and 16 involving rural community teachers.

Teachers, particularly those in poor rural districts, had very specific demands not seen in many other sectors, reflecting their employment status, low pay and lack of benefits. A relatively small proportion of cases (43.2 percent) involved wage arrears, while 26.4 percent included demands for higher pay, and 22.5 percent concerned social insurance payments.

Teachers would often organize strikes and sit-ins, with occasional gatherings outside government buildings, which would often lead to confrontation with the police.

Please see our research report Over-worked and under-paid: The long-running battle of China’s teachers for decent work, which covers teachers’ collective action from 2014 to 2015 for more details.