Pushing the trade union to take gender discrimination in China seriously

08 February 2018Discrimination against women is commonplace in China and, in many employment recruitment advertisements, quite blatant and overt. Most people choose to ignore it or just accept it as a reality of the labour market but not college student Xiao Chunqing.

After looking through the listings on the popular advertising website 58.com last November, Chunqing (a pseudonym) decided to take action: She sent a total of 87 complaint letters to the local offices of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) and local labour bureaus in 29 provinces across China.

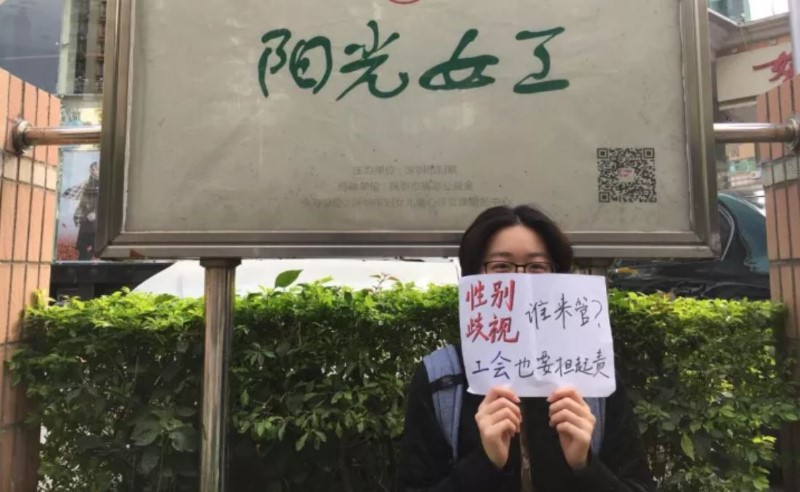

Who is going to tackle gender discrimination? The trade union needs to shoulder its responsibilities

In a blog post on Jianjiao, a women workers’ online community, Chunqing noted:

It is the duty of the union to represent workers in negotiations with employers, it should not just sit on its hands. Neither should the Trade Union Law just exist on paper. The union should shoulder its legal responsibilities towards workers by defending their rights. When job seekers stumble on recruitment ads that overtly practice gender discrimination, the union has the obligation to provide assistance.

The blog post also quotes Article 22 of the Trade Union Law, highlighting the trade union’s legal obligation to represent workers when employers violate their rights, putting a special emphasis on its duty to protect the rights and interests of female workers.

The response from the various union and government offices so far however has been underwhelming. In a follow up post on 2 February, Chunqing revealed that she had received just 13 replies, only three of which came from local unions, the others were from local labour bureaus.

The three replies from local unions in Changsha, Guangzhou and Guiyang, highlighted quite different attitudes towards gender discrimination and the role of the trade union in tackling it.

The reply from Changsha’s municipal union stated that they took the gender discrimination case very seriously: they had sent staff to look into the matter and reprimanded the offending company.

Guangzhou’s union looked into the complaint but their reply simply reinforced existing prejudices about the kind of jobs women are suited to. The reply stated:

“The position advertised requires doing nights shifts, from a personal safety angle it is understandable they prefer male applicants, women are certainly not suitable for the position.”

The reply from Guiyang was even less encouraging. The union refused to investigate and was condescending towards the complainant: “Where do you live? Are you applying for the job or what?” the reply asked.

The replies from local labour bureaus likewise ranged from proactive to dismissive to outright ignorant of their legal obligations. The replies exposed wide differences in how local officials viewed gender discrimination and how they should proceed once they receive a complaint.

Chunqing said she was not disappointed with the replies she had received so far, noting: “I had no expectations to begin with. This was an experiment; my goal was to remind the local unions of their legal obligations. Sending letters in itself is not enough, this is just a first step.”

Chunqing pointed out that the overt gender discrimination seen in recruitment ads stems from generalised misconceptions on gender roles, but stressed that it is government negligence and trade union inaction that allows it to persist.

The trade union was in effect condoning exploitative business practices by leaving workers without a voice or a channel for negotiations, she said, adding: “It’s time for the union to play its role as the negotiation facilitator between employees and employers.”

For more information on this important issue please see our background article on workplace discrimination in China.