Why has there been a drastic reduction in worker protests in Dongguan?

28 September 2017The southern city of Dongguan used to be known as China’s “factory to the world.” For many years, it was also a major centre of worker unrest with almost daily protests over factory closures, the non-payment of wages and social security arrears.

Indeed, the city made international headlines in April 2014 when around 40,000 workers at the massive Yue Yuen shoe factory complex went out on strike for two weeks demanding the payment of social insurance contributions in arrears.

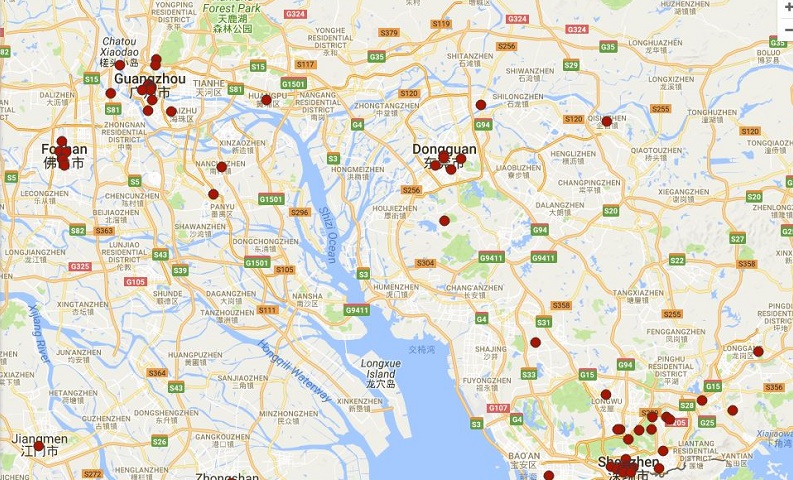

Worker unrest reached a peak in Dongguan around 2014 and 2015 when thousands of factories closed down, downsized or relocated to lower cost areas in China or abroad. CLB’s Strike Map shows that Dongguan accounted for 24 percent of all worker collective protests in Guangdong in first nine months of 2014, and 23 percent in the first nine months of 2015. That total fell to 17 percent in the first nine months of 2016 and was just eight percent for the first nine months of this year. See maps below.

Worker protests in Guangdong in the first nine months of 2015

Worker protests in Guangdong in the first nine months of 2017

The municipal authorities in Dongguan claim this dramatic fall in the number of worker protests is the result of its newly established “labour relations early warning system,” in which the human resources and social insurance departments, police, etc. combine to intervene when problems arise and ensure that labour disputes are resolved before they escalate into strikes or protests.

The resolution process reportedly focuses on mediation and dialogue, ensuring that the relevant provisions of labour law are adhered to and in making sure both the workers and management understand the importance of social and economic stability.

The authorities claim there has been a 69 percent reduction in the number of collective protests by workers over the last year and a 71 percent reduction in the number of factory bosses skipping town without paying wages. The government claims the city is now basically free of wage arrears, although there were two relatively minor protests by factory and construction workers over the non-payment of wages on 12 September alone.

The Dongguan authorities should be commended for taking a more proactive approach to labour conflict but their actions do seem to be a case of closing the stable door after the horse has bolted. Although there is still a large manufacturing base in Dongguan it is now a shadow of its former self. Tens of thousands of small and medium-sized enterprises, particularly those in low cost and labour intensive industries such as garment, shoe and toy manufacturing, have already moved out of Dongguan over the last decade.

The manufacturing enterprises that are left tend to be larger, more stable businesses that can afford to pay better wages and are less likely to see labour disputes arise. Meanwhile, many of the old factory districts have been taken over by logistics centres catering to the online retail business. These logistics centres can easily take advantage of the well-developed highway system that links Dongguan’s dispersed townships with Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

As the logistics industry develops, however, the authorities will have to focus more attention on the pay and working conditions of delivery drivers and package handlers many of whom are very poorly paid and work long hours and are increasingly willing to stage strikes and protests themselves when management pushes them too far.