Hotel workers fight back in low paid service jobs

28 August 2017China’s hotel workers are among the lowest paid in the country, though they account for more than their fair share of resistance to poor working conditions.

Although the hotel industry accounts for only 1.5% of employment, according to official statistics, hotel workers make up 2.6% of all worker collective actions, according to CLB’s strike map; in services alone, hotel worker actions account for 15% of strikes and protests in the industry so far this year.

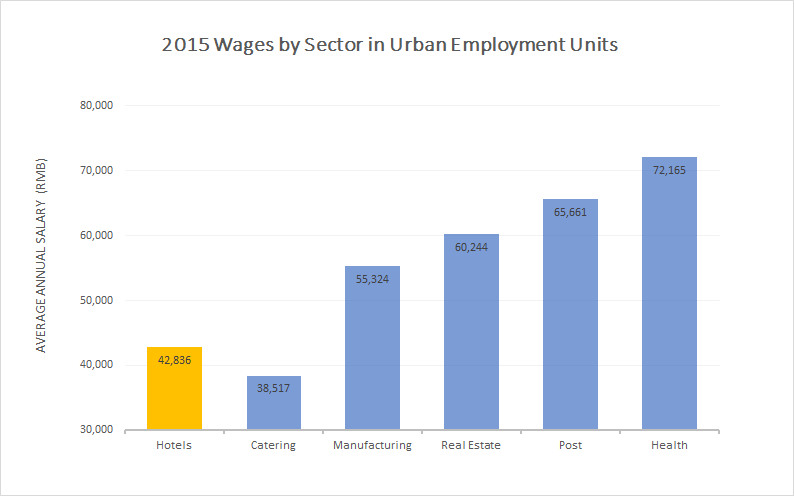

The hotel industry is just the latest example of how low pay and poor working conditions stand behind the booming service industry. According to the latest government statistics, hotel workers are among the lowest average paid of any industry:

Source: 2016 China Labour Statistical Yearbook

A new report (in Chinese) by Hong Kong-based labour rights organisation Worker Empowerment (WE) provides an unprecedented look into the lives and struggles of service sector workers, including those in the hotel industry. A survey of Shenzhen hotel workers last year showed that only half of workers had a labour contract, and worked for alarmingly low pay.

Far below government statistics, the WE report showed that pay among workers at hotels in Shenzhen, one of China’s most expensive cities, is between 2,000 to 3,000 yuan per month. In 2017, Shenzhen's government set the local minimum wage at 2,135 yuan per month.

Hotel workers are subject to the same poor conditions regardless of the level of luxury of their workplaces. Labour conditions in five star high-end hotels are not necessary better than in their three-star counterparts: only about 55% of workers surveyed have a labour contract, 36% are interns whose contract conditions are negotiated between schools and hotels, not the students themselves. Meanwhile, agency or dispatch workers, who have no direct contractual connection with the hotels they work for, make up about 10% of the workforce surveyed by WE.

While most staff are low paid, income gaps within hotels can be enormous. In one hotel surveyed by WE, the chief executive earned around 100 times the salary of the lowest paid employee: front line staff earn around 2,000 yuan per month - barely enough to make it to the next pay cheque - while a general manager behind a desk makes 200,000 yuan. Salaries for middle management and other senior administrative positions hover between 3,000 to 6,000 yuan, according to WE.

The situation is even worse for those working in the associated services of the hotel, like bars and restaurants. Karaoke bars at hotels, for example, employ service staff with a monthly minimum wage of 600 yuan.

To make matters worse, application of flexible working hours leaves many front line staff with few chances to clock in overtime or holiday double pay, forcing them to work extra shifts late at night or during holidays with none of the legally mandated overtime compensation.

Incidents in the hotel industry are often smaller in scale than those of other industries, but they occur in every corner of China, from the most developed cities to the farthest reaches of the country.

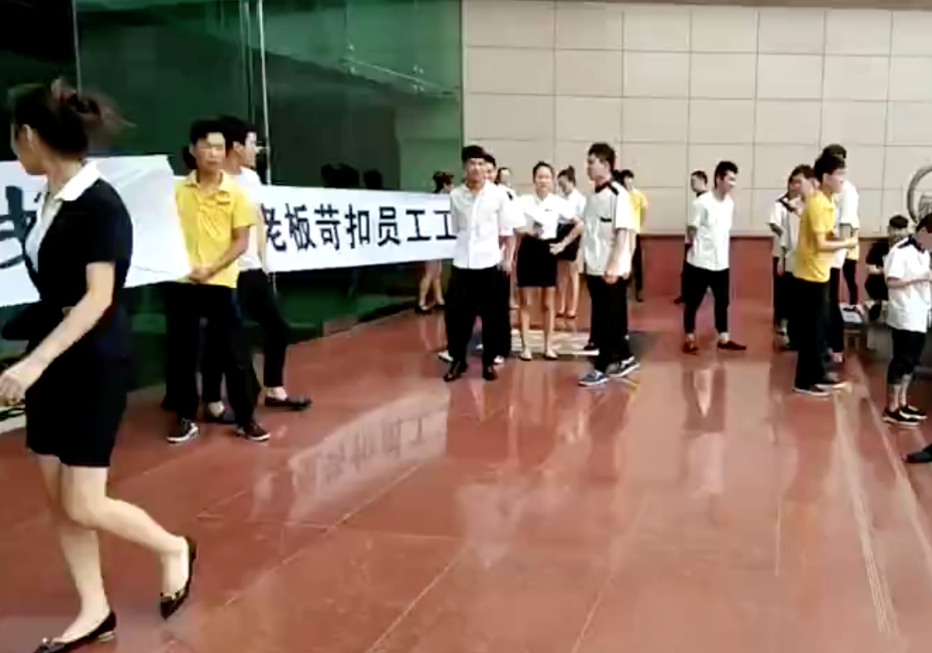

On 14 August three cooks in Gansu threatened to jump from the roof of a hotel where they worked, protesting wage arrears. Police reported that, after they intervened, their boss paid their wages while the workers were placed in administrative detention. A week earlier a handful of workers at the Zhizhen Hotel in Xi’an blocked off the entrance to the building in a demonstration protesting pay deductions. Just last Monday, a group of workers at a hotel spa threatened to jump from the top of a building protesting wage arrears.

Demonstration by Zhizhen hotel workers in Xi'an, Shaanxi province earlier in August.

Low wages, income disparities, lack of labour contracts, increasing informalisation and deteriorating working conditions have set the stage for increased levels of labour unrest. Workers are ready to stand up for themselves and reclaim their fair share. If their demands are not addressed and deteriorating labour conditions persist, employers and relevant government agencies should not expect them to just go away.