Inequality rising, even accelerating, in China

26 July 2017Latest statistics show that inequality is on the rise across income groups and regional divides, and even accelerating in China.

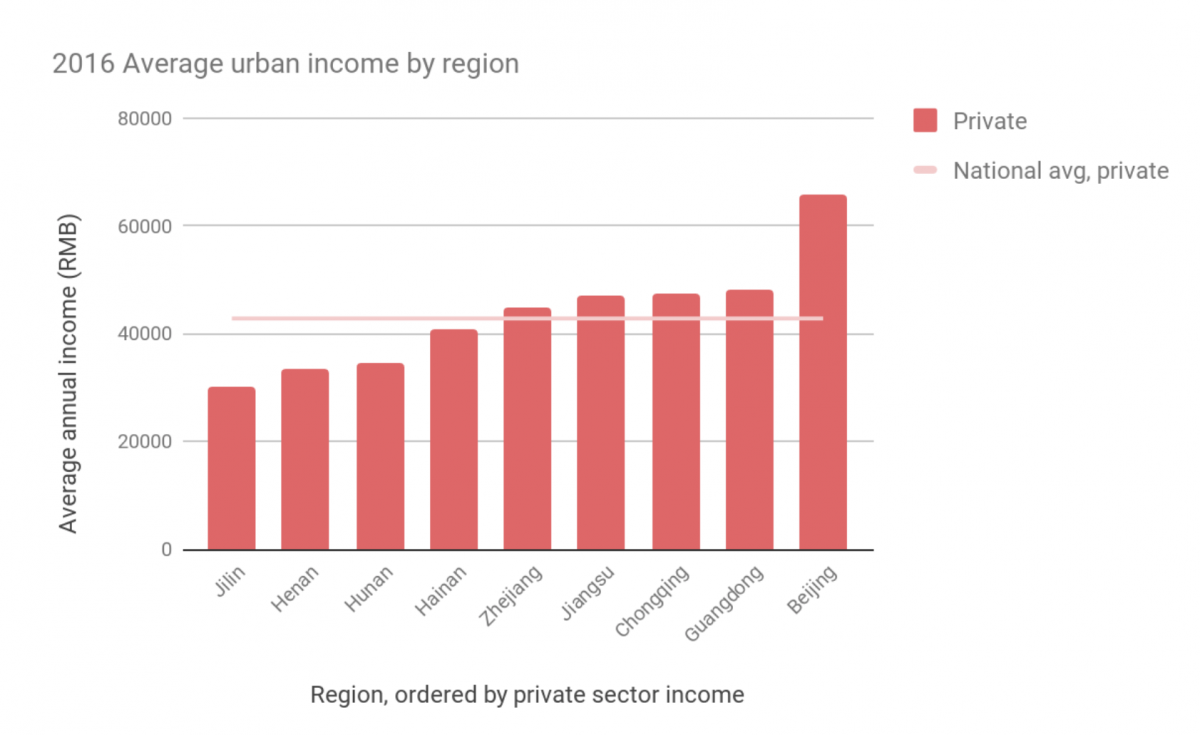

Regional wage data from the National Bureau of Statistics released this month show large gaps in the average income between localities. Average urban annual salaries for private enterprises in Beijing, at 65,881 yuan, for example, are twice that of Jilin province, at 30,184 yuan.

(Source: National Bureau of Statistics)

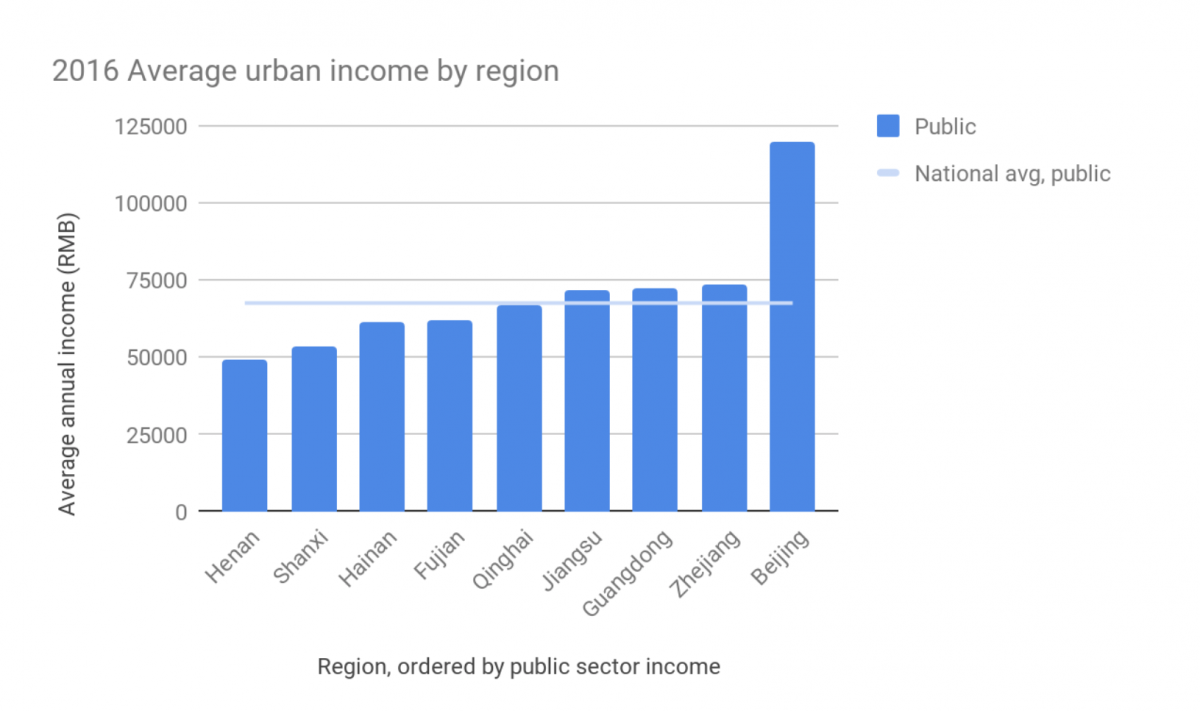

(Source: National Bureau of Statistics)

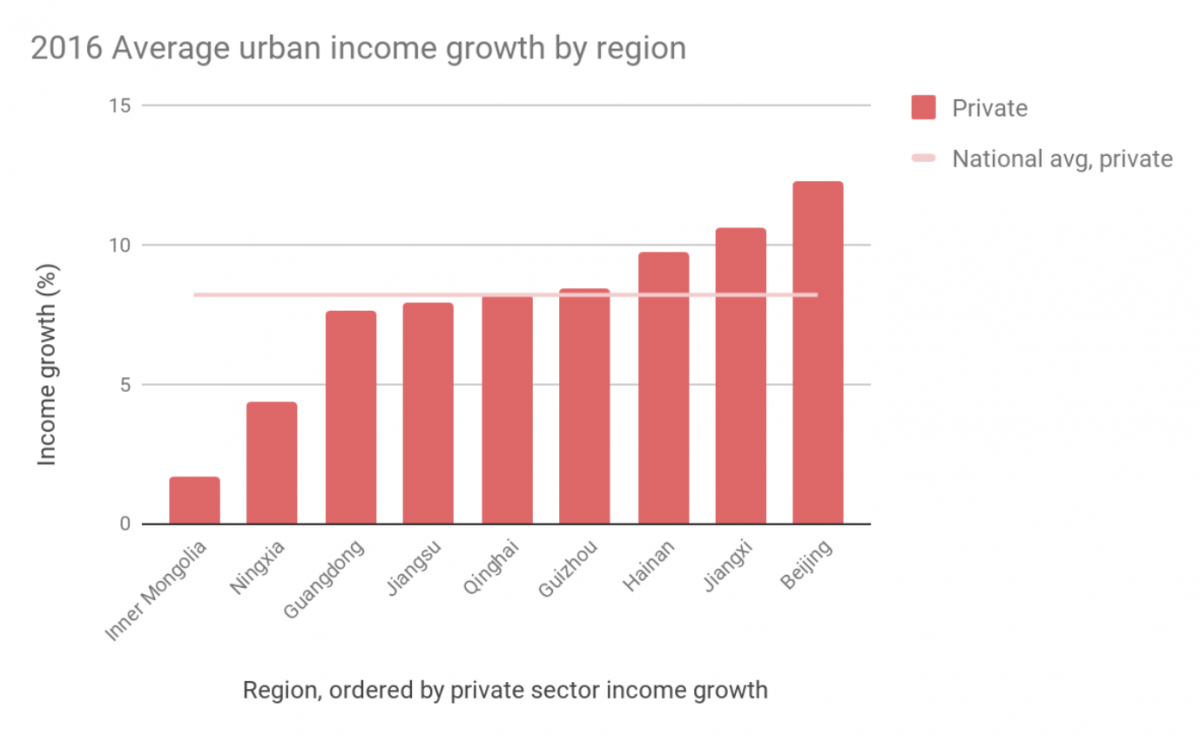

Moreover, higher income regions are also experiencing the fastest wage growth, driving richer and poorer provinces farther apart. The data show that private sector wages in Beijing grew by 12.3% last year, while poorer regions like Inner Mongolia and Ningxia only grew by 1.7% and 4.4%, respectively.

(Source: National Bureau of Statistics)

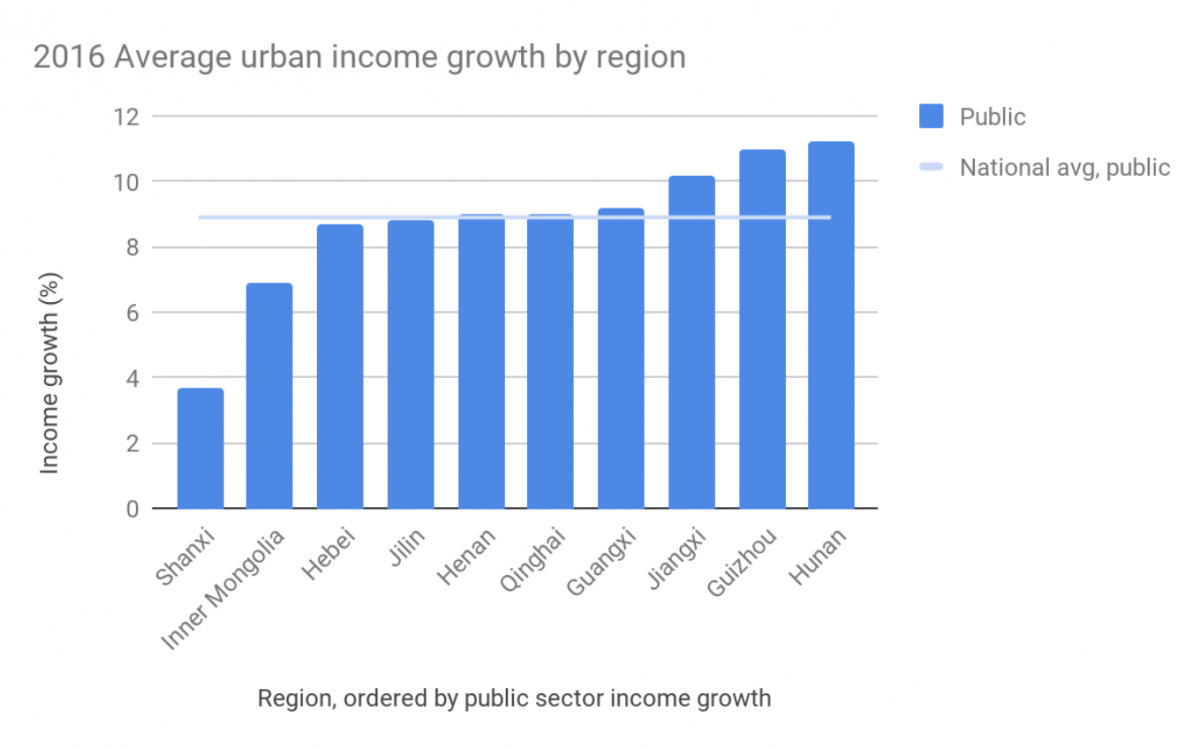

(Source: National Bureau of Statistics)

The growing regional disparities are consistent with several long-term trends in inequality in China, including the growing urban-rural divide, as well as national income and wealth divides. These alarming trends were captured in a recent landmark investigation of inequality in China between 1978-2015 by world-renowned inequality researchers Thomas Piketty, Li Yang and Gabriel Zucman.

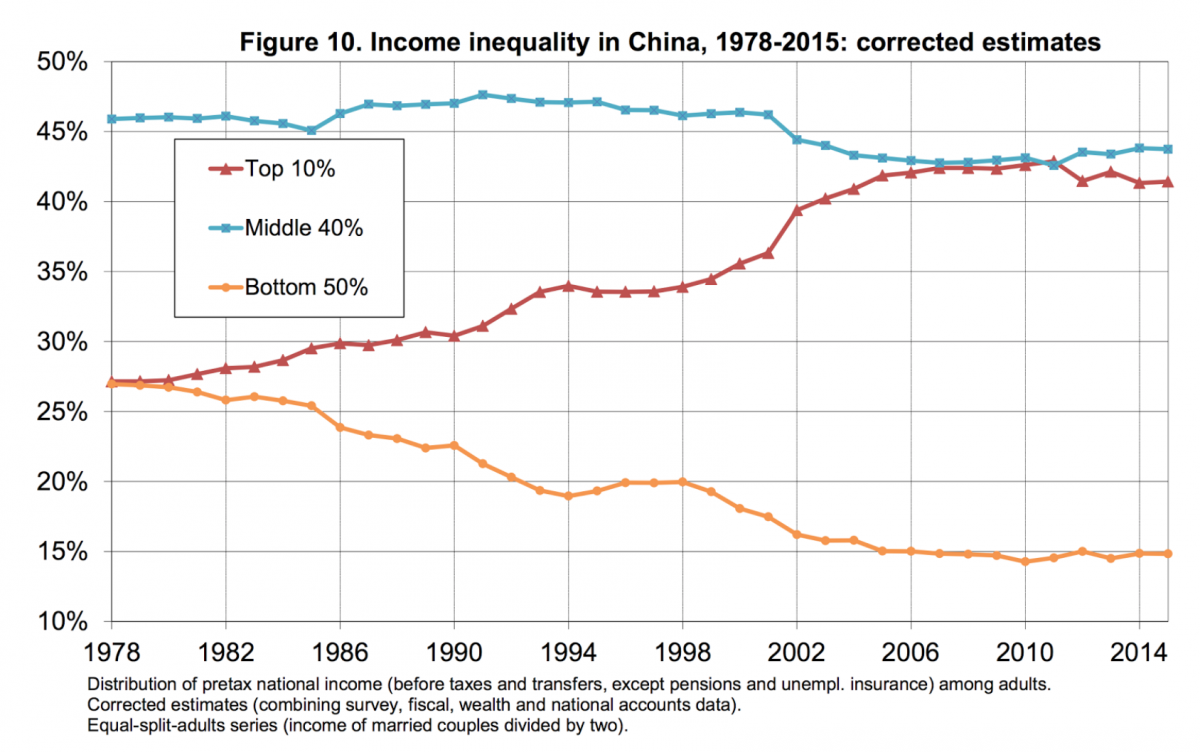

According to the report by Picketty et al, the gap between the poor and the rich is widening: “the top 10% income share rose from 27% to 41% of national income between 1978 and 2015, while the bottom 50% share dropped from 27% to 15%.”

(Source: Capital Accumulation, Private Property and Rising Inequality in China, 1978-2015, Thomas Piketty et al)

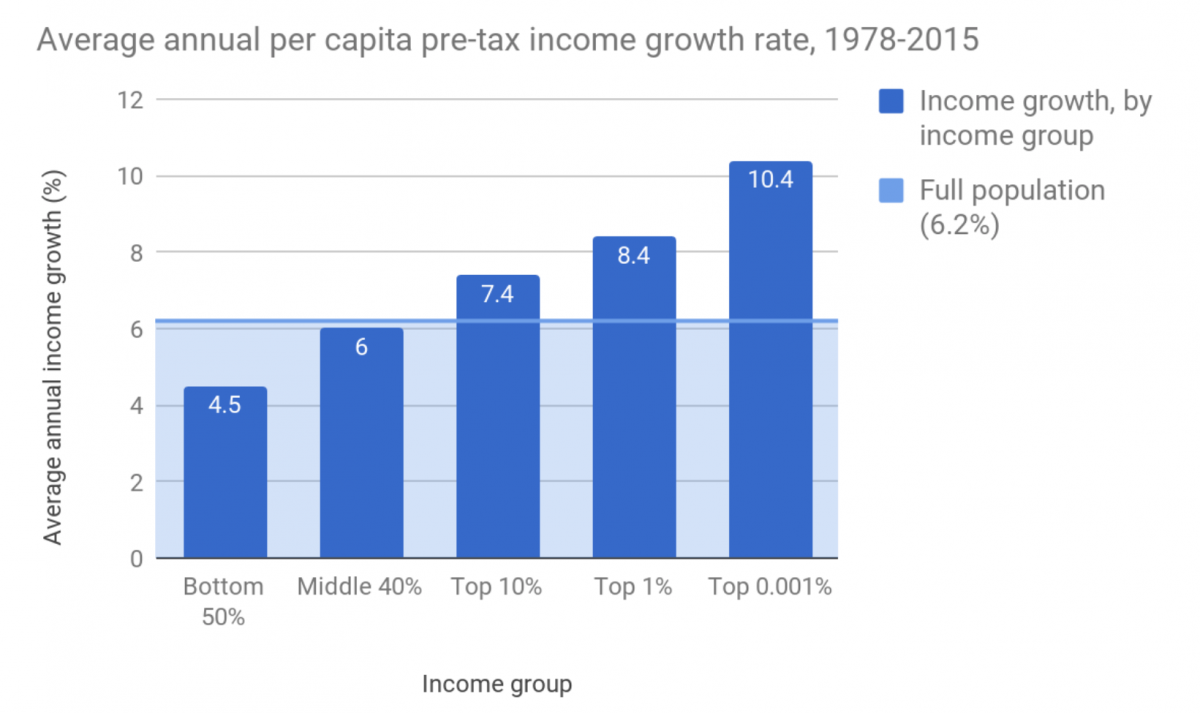

The incomes of the wealthiest have skyrocketed over the past four decades of China’s development. While China’s annual GDP growth was often in double digit figures since 1978, the average annual income growth for the bottom 50% of the population was only 4.5% per year, while income for the top 1% grew at double that rate; the super wealthy in top 0.001% saw incomes grow the fastest of all, at 10.4% per annum.

(Source: Capital Accumulation, Private Property and Rising Inequality in China, 1978-2015, Thomas Piketty et al)

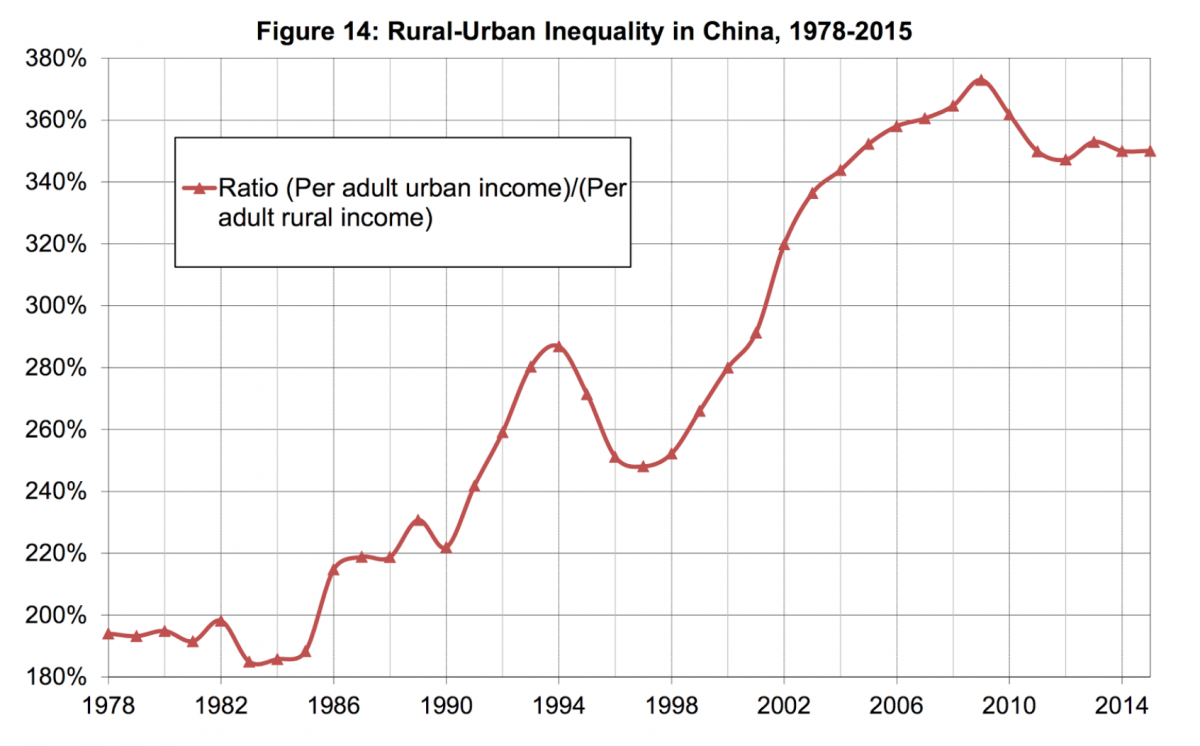

In terms of the rural-urban divide, Piketty et al found that the ratio of urban to rural average incomes rose from less than 200% in 1978 to about 350% in 2015.

(Source: Capital Accumulation, Private Property and Rising Inequality in China, 1978-2015, Thomas Piketty et al)

Some have claimed that inequality in China has been slowly falling over the past few years (full report here), though more recent data casts doubt on these conclusions. The Piketty study noted that the real gains made by China’s richest has likely been obscured due to lack of sufficient data since 2011, and that the share taken by the wealthiest is probably much higher. In addition, China’s already high Gini coefficient increased slightly last year up to 0.465; any number over 0.4 is considered “severe” by the United Nations.

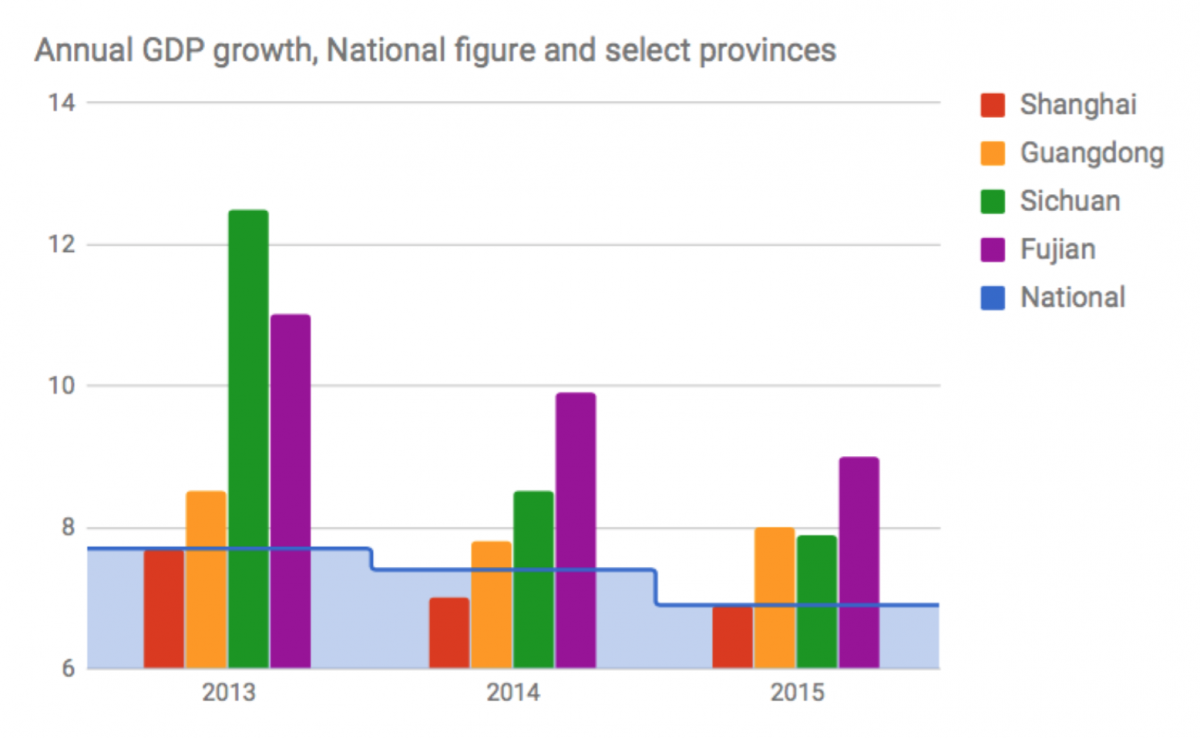

Though the richer and poorer are being driven farther apart, there are still signs of hope. In terms of regional inequality, GDP growth in these poorer regions is growing rapidly compared to richer provinces. Annual GDP growth in Fujian and Sichuan, for example, has far surpassed more developed regions like Shanghai and Guangdong.

(Source: National Bureu of Statistics)

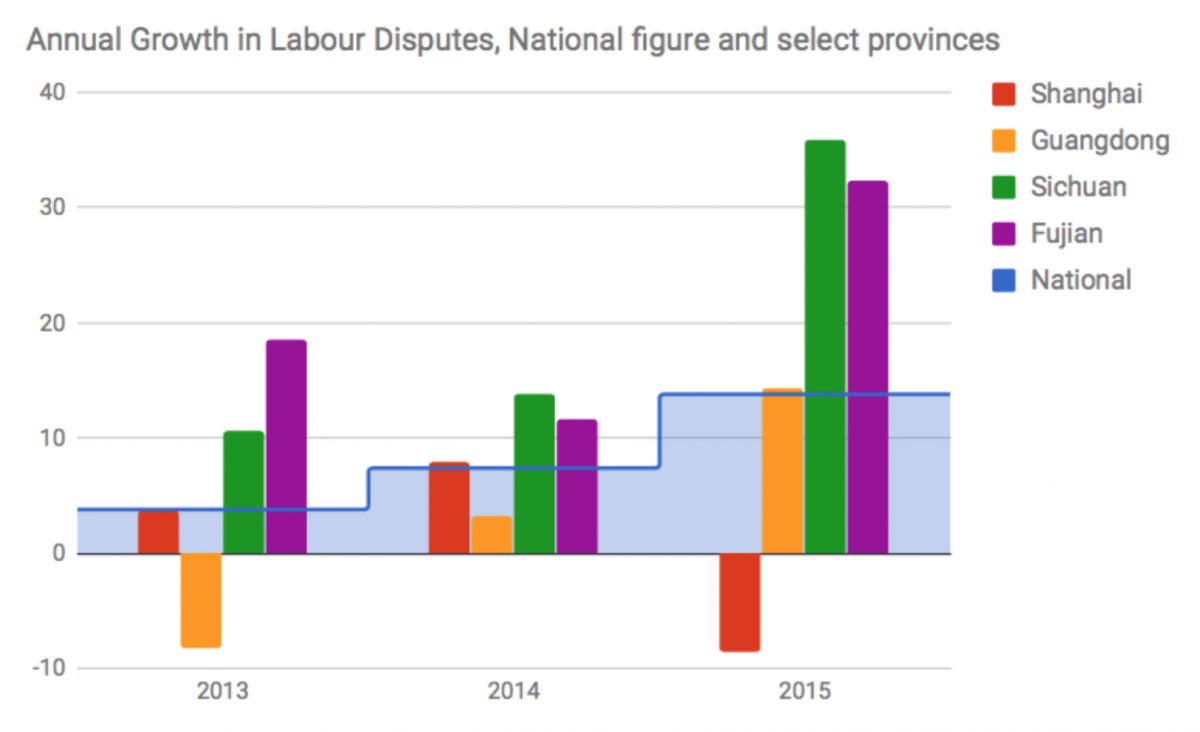

Increased GDP growth, however, also brings increased labour tensions. Provinces like Fujian and Sichuan have seen an explosion of labour disputes in recent years, while annual change in Shanghai and Guangdong has had both small contractions and growth in labour disputes, according to official statistics.

(Source: National Bureu of Statistics)

Workers have been a driving force behind resistance to inequality, but their power has yet to be leveraged through needed reforms to China's labour relations. As these labour tensions continue to unfold, officials face a choice: to continue to muddle through the volatility of labour discord that comes with rapid growth, or face the fact that labour relations in China are in desperate need of reform.

Trade union reform coupled with collective bargaining practices would empower workers across China to defend their rights, gain a greater -and fairer- share of the pie, and fight back against growing inequality. Through reform, workers, employers and officials may still develop a more reasonable, predictable and fair distribution of wealth for all.