Workers at unsafe jobs left with nothing after strike

18 July 2017After two weeks on strike, Mr. Wang has been left with no job, no severance, and a splitting headache.

He was until last week one of nearly 2000 workers at Zama Precision Industry in Shenzhen, wholly-owned by German power tool giant Stihl. Mr. Wang and more than one hundred of his colleagues at unsafe jobs are still campaigning for medical treatment after working for years at dangerous painting jobs without proper safety equipment.

Workers meet to gather demands and discuss strategy

Zama workers ended their two week strike in early July demanding severance and compensation during the factory’s relocation to Huizhou, around 100 kilometres to the northeast.

Zama workers had been organising through the factory since April when they heard of the factory’s plans to relocate. Workers from across the factory collected various demands, including health and safety grievances, social insurance, and severance payments; they approached management for negotiations, demanding compensations be paid to them in full before the factory relocation.

Mr. Wang worked at Zama for five years, and for the last year and a half as a painter. He and and 150 of his colleagues worked under dangerous conditions and were exposed to harmful chemicals on a daily basis. “At my post there was absolutely no safety equipment, no masks, no gloves, and no special subsidies like there are at other factories,” said Wang.

The workers suffer from persistent headaches and fear they have incurred occupational illnesses while at Zama. They selected 10 representatives and demanded management pay for medical examinations to check for occupational injuries before the factory relocated.

With worker demands building up, management refused to pay compensation of any kind before workers either signed new contracts with the company or voluntarily resigned. Zama workers rejected the proposal and went on strike on 26 June. Workers demonstrated within the factory grounds and blocked exits to prevent the shipment of goods and relocation of equipment.

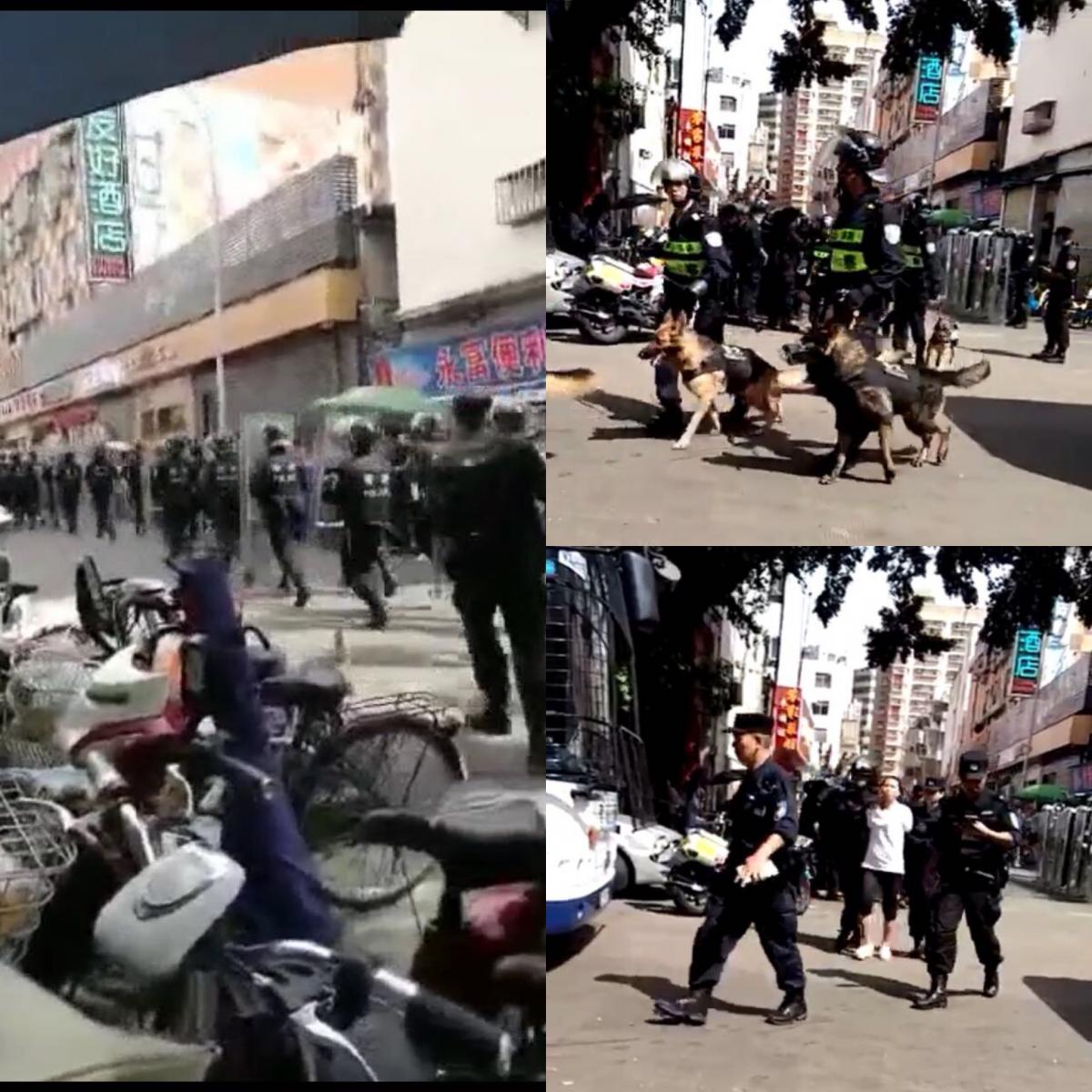

The following day, riot police with dogs arrived at the scene. Five workers were arrested, and over a dozen injured with pepper spray. “It was probably management who called the police” said Mr Wang.

Police intervene in Zama strike: police with riot gear rush toward factory (left) police dispatch canine units (upper right) one Zama worker arrested by police (bottom right)

After the police intervention, management made a final offer at a rate far lower than workers could accept. In response, hundreds of workers resigned en masse, among them Mr Wang and most of his colleagues at dangerous jobs, still nursing headaches. They are now looking for work. “The factory promised us a medical check before we left, but now we haven’t gotten anything. We have heard nothing from them,” said Mr Wang.

In 2015 Stihl signed a Code of Conduct for its suppliers under the UN Global Compact and International Labour Organization, committing them to a “safe and hygienic working environment” that meets national standards. Article 37 of China’s Work Safety Law clearly stipulates that employees should be provided protective equipment on the job.

Mr. Wang and many of his coworkers have yet to receive their severance payment and promised medical check, and have resolved to fight for their rights, “We are following up, but so far nobody has listened to us,” he said.

This year’s strike was the latest of three strikes in four years at Zama. In 2013, 1000 temporary workers at Zama went on strike, where two rounds of failed negotiations resulted in police intervention.