Introduction

China is undeniably a safer place to work than it was a decade ago. However, accident rates, death tolls and the incidence of occupational disease are all still comparatively high, with about 75 deaths from work-related accidents each day on average in 2020, according to official figures. New work hazards have emerged as the economy develops, and many employers continue to prioritise productivity and profit well above work safety.

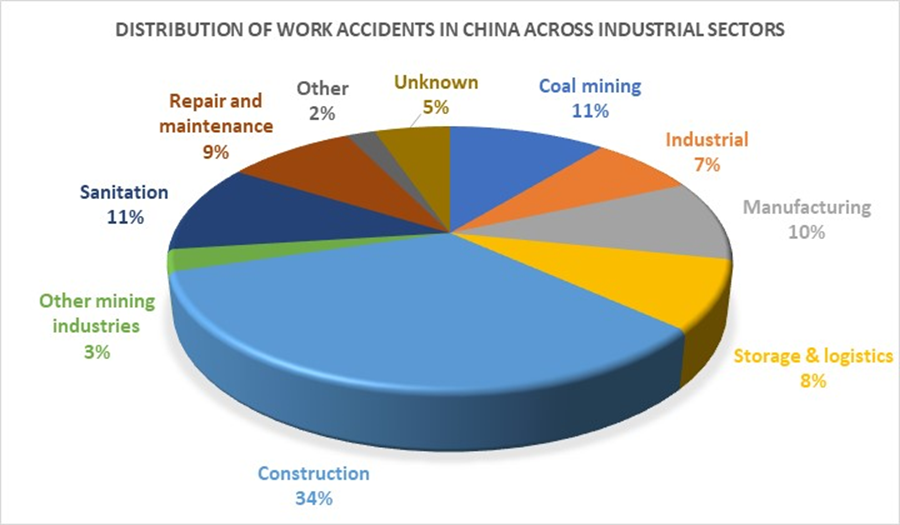

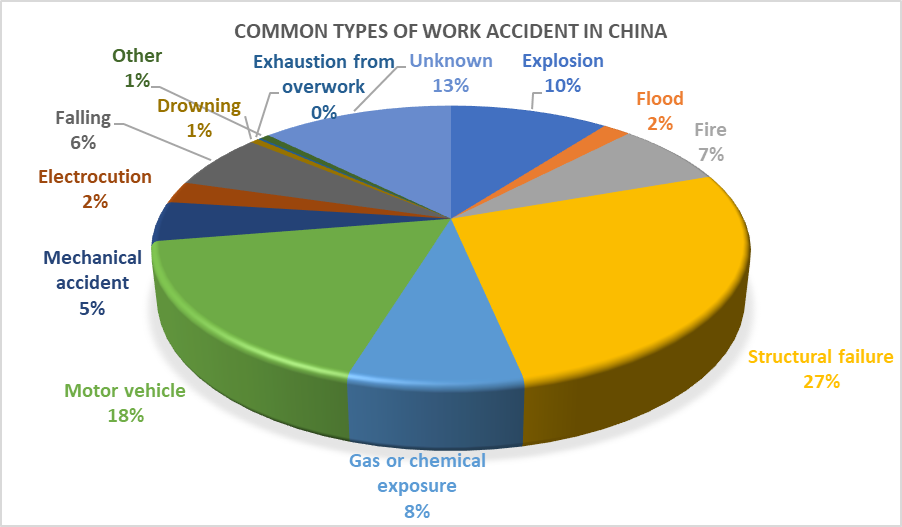

In this article, we provide a historical overview of work safety in China and assess the extent to which the current legal and administrative framework has actually helped to protect workers. We use official reports and CLB’s Workplace Accident Map to pinpoint China’s most dangerous industries and examine the most common hazards faced by workers today, including occupational disease, overwork and dangerous living conditions. Contrary to many expectations, China’s most hazardous jobs are not in coal mining but in the poorly-regulated construction industry. The construction industry accounts for more than a third of all the incidents recorded on the Work Accident Map and these incidents most commonly involve some kind of structural or mechanical failure or workers falling from a height.

Workplace accidents in China are sadly routine and commonplace, usually involving a handful of people at most. These “minor” incidents do not attract the kind of mass media and government attention that major tragedies like the 2015 Tianjin port explosion get. As a result, the relatively prosaic underlying issues that give rise to more typical workplace accidents and occupational disease, such as a lack of safety equipment and training, as well as lack of supervision by trade unions, are rarely addressed. It is clear that China will be unable to create and maintain a truly safe working environment until these problems are tackled at the grassroots by the government, trade unions, employers and workers alike.

For the Chinese version of this article please see 安全生产 on our Chinese website.

From coal miners to delivery drivers: Changing patterns in work hazards over the last decade

During the economic boom of the 2000s, China had a terrible work safety record. The country’s coal mines in particular were widely recognised as the most dangerous workplaces in the world, with at least 7,000 miners losing their lives in 2002 alone. There were several occasions during this period when more than one hundred miners died in a single incident, usually the result of a gas or coal dust explosion, including three major accidents in the five months between October 2004 and February 2005 that killed a total of 528 miners (see table below).

→ Please scroll to right

| Date of accident | Location | Official death toll | Cause of accident |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 October 2004 | Daping Coal Mine, owned by the Zhengmei Group in Henan | 148 | Gas explosion |

| 28 November 2004 | Chenjiashan Coal Mine, Tongchuan Mining Bureau, Shaanxi | 166 | Gas explosion |

| 14 February 2005 | Sunjiawan Coal Mine, Fuxin Coal Industry Group, Liaoning | 214 | Gas explosion |

| 7 August 2005 | Daxing Coal Mine, Wanghuai, Guangdong | 123 | Flood |

| 27 November 2005 | Dongfeng Coal Mine, Qitaihe branch of Heilongjiang Longmei Group, Heilongjiang | 171 | Coal dust explosion |

Accident and death rates have steadily declined since the mid-2000s and reached a new low of 228 fatalities in 2020. 2018, was the first time China recorded fewer than 0.1 deaths per million tons of coal produced, and that figure declined further in 2019 to 0.083 deaths, and then to 0.058 deaths in 2020. The decrease in accident and death rates stems largely from the mass closure and consolidation of mines, especially in the coal heartland of Shanxi, at the end of the 2000s, and the drop in the price of and demand for domestic coal in the 2010s which led to around one million miners being laid off. There is not much evidence that coal mine operators are significantly more safety conscious than before, and there is still a danger that accidents will increase again if demand for coal increases and mine owners decide to boost production or re-open abandoned mines without going through the necessary safety procedures.

Major incidents still happen annually. On 12 January 2019, 21 miners died when a roof collapsed at the Lijiagou coal mine in Shenmu, northern Shaanxi. Towards the end of 2020, a string of major coal mine accidents occurred. On 27 September 2020, 16 miners died from carbon monoxide poisoning when a mining conveyor belt caught fire at Songzao Coal Mine in Chongqing. On 29 November 2020, 13 people died when Yuanjiangshan Coal Mine in Leiyang, Hunan, flooded. On 4 December 2020, 23 miners died from carbon monoxide poisoning due to a gas leak at Diaoshuidong Coal Mine in Yongchuan, Chongqing.

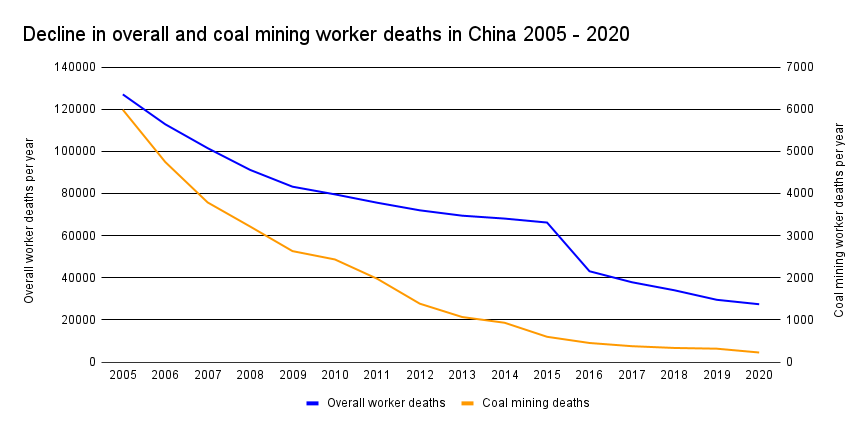

The overall decline in worker death and accident rates in China has been steady but not nearly as rapid as in the coal industry (see graph below). From 2005 to 2019, the number of coal mine deaths fell by 96 percent while the overall annual rate of decrease was just around 77 percent. Moreover, the overall decrease included a significant drop in the number of deaths from 2015 to 2016 due to a change in the way official statistics were calculated. From 2015 onwards, so-called “non-production accidents” were excluded from the total figure, according to the Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2016 National Economic and Social Development. However, the exact calculation method remains opaque.

Although workplace safety has improved, major problems remain and, importantly, the nature of workplace hazards has changed significantly. China’s economy has shifted away from heavy industries like coal and steel production towards service industries and e-commerce platforms with more informal patterns of employment, and it is in these industries that we see an increase in the number of accidents, injuries and deaths.

One of the most dangerous occupations in China today is that of delivery driver. According to Shanghai traffic police, in the first half of 2019, there were 325 road accidents involving package or food delivery drivers, which resulted in 5 deaths and 324 injuries. One report from 2017 found that a Shanghai delivery driver is either badly injured or dies in a traffic incident every 2.5 days on average, while in nearby Nanjing, there are 18 accidents involving delivery drivers every day. However, many of these accidents slip through the cracks of the official statistics, as in the case of food delivery driver Yang Song, who died while working a 14 hours shift in Chongqing in August of 2017. The police told Yang’s bereaved mother that he was “solely responsible” for the accident, and the food delivery company insisted that Yang was merely an “independent contractor,” and therefore his case could not be classified as a work accident or covered by work-related accident insurance.

In their bid for market domination, major food delivery platforms such as Meituan try to reduce costs as much as possible and this places tremendous pressure on drivers to deliver more orders in a shorter period of time, leading to a higher frequency of accidents. As one Meituan delivery driver commented during a worker protest in Kunming over harsh new working conditions that forced drivers to take huge risks in order to make deliveries in time: “Am I supposed to drive through red lights? Putting this kind of pressure on us is simply toying with our lives.” On 21 December 2020, a 43-year-old delivery driver Han Mouwei working for food delivery giant Ele.me, died suddenly on the way to delivering his 34th order for that day. Ele.me initially offered his family 2,000 yuan in compensation, raising it to 600,000 yuan only following public outcry.

The legal and administrative framework for work safety

China’s 2002 Work Safety Law (安全生产法) provides the main legal framework for the rights and responsibilities of workers, trade unions, employers and government agencies in creating and maintaining a safe workplace. Some of the key provisions are:

When employees discover an emergency that directly endangers their personal safety, they have the right to stop working or evacuate the workplace after taking emergency measures. Employers may not cut pay, benefits, dismiss any worker who stops work or takes emergency evacuation measures under the emergency conditions mentioned in the preceding paragraph (Article 55).

- Employees have the right to criticise, report on their employer, stop work, and lodge charges against any work they deem to be unsafe. They have the right to refuse orders which break rules or force them to undertake a risky job. Employers may not cut the pay, benefits, or dismiss any worker, who makes a criticism, a report, brings a charge, or refuses to comply with orders which break rules or force them to undertake a risky job. (Article 54).

- Employers must provide employees with safety equipment that meets national or industry standards. The employer’s work safety personnel should conduct regular work safety inspections suitable to the nature of the work (Article 45, Article 46).

- Employers must also provide safety training, and not allow any worker who has not had proper training to work on the job site (Article 28).

- Employers must purchase work-related injury insurance for their employees and pay premiums (Article 51).

- Trade unions supervise work safety in accordance with the law. They organise employees to participate in management of work safety to safeguard the rights and interests of employees. When formulating or revising regulations or systems related to work safety, employers should take into account the suggestions of the trade union (Article 7).

- The trade union has the right to demand employees correct any violation of work safety laws and regulations, and infringements on worker rights and interests. When they discover any violations, they can raise suggestions. Employers should respond promptly, and if they discover any workplace condition which endangers workers’ lives and safety, the union can suggest employers organise evacuations of employees. Employers must do this immediately. Trade unions can participate in the investigation into workplace accidents, give opinions to relevant departments and demand relevant personnel be held accountable (Article 60).

- Journalists have the right to report on violations of workplace safety for the purposes of educating the public (Article 77).

In short, the law places the onus on employers to protect employees and guarantee a safe working environment, and gives workers and trade union officials the right to monitor and participate in the management of work safety. In reality, however, employers are free to ignore their obligations and employees are often unaware of their rights regarding work safety. Moreover, trade union officials are usually under the sway of management and will not intervene to report or remedy safety violations.

As representatives for workers, trade unions should be supervising how companies carry out work safety measures, mobilising front-line workers to report potential safety hazards, working to prevent workplace accidents, and taking an active role when they do happen. However, trade unions at all levels tend to limit their responsibilities to work safety-related training and education. Since enterprise trade unions are usually under the control of management, they are unwilling to intervene when it comes to work safety, let alone report or correct violations.

Over the years, trade unions at all levels have mainly carried out contests and lectures to raise awareness of work safety, handed out flyers, and organised cultural and sports activities. They rarely protect frontline workers by investigating and reporting hazards. When a workplace accident occurs, the trade union is only one of many participants in the ensuing investigation team. Unions have not fulfilled their supervisory role for many years, and have never been held accountable for this.

Trade unions often explain their failures away by saying that they have no enforcement powers, that the incident is outside their jurisdiction or by pointing to the company not having established a union. But the Trade Union Law, Work Safety Law, and Labour Law among others assign trade unions the responsibility of supervising work safety. When they fail to fulfil their responsibilities, they should be held accountable. However, in the current work safety model of government, administrative departments often take over roles for managing and supervising work safety. (For more analysis of how supervising work safety works in practice, please refer to Returning the union to its rightful place in supervising work safety.)

It is the responsibility of local government officials, under the overall purview of the Ministry of Emergency Management (MEM), to ensure that all workplaces comply with work safety regulations. The MEM was established in March 2018 to oversee the management of a wide range of natural and made-made disasters. The old State Administration of Work Safety was formally dissolved at the same time but the State Administration of Coal Mine Safety (renamed the National Coal Mine Safety Administration) remained intact as part of the new mega-ministry.

In spite of the national government reorganization, most local government offices responsible for work safety issues are understaffed and have little time or incentive to carry out routine workplace inspections. Officials spend most of their time investigating and writing up detailed and exhaustive reports on the accidents that occur within their jurisdiction. Just about the only time officials do exercise any power is in the immediate aftermath of a major disaster when draconian and heavy-handed measures are sometimes used to crackdown on violators.

The government’s approach to work accidents can best be described as reactive and coercive. Very little happens until a major accident, after which local officials go into crisis containment mode. The two main concerns of the government are to determine the cause of the accident and punish the guilty parties, business owners and local officials alike. Within two weeks of the 2015 Tianjin port explosions, for example, 12 people were arrested and 11 officials investigated for dereliction of duty or abuse of power. Tianjin was however an extreme example and, in many cases, the guilty can go unpunished, especially after small-scale accidents when very little remedial action is taken.

When work safety inspections do occur, in the wake of an accident, business owners are usually well-prepared and can sometimes persuade inspectors to turn a blind eye to safety violations with gifts and other advantages. Even if businesses are cited for violations, very little follow up action is taken and businesses can carry on as normal without making any substantive changes to their production regime. It is not unusual for accidents to occur in hazardous workplaces that had either recently “passed” inspection or had been cited for violations but taken no action. For example, the explosion and fire at the Hebei Shenghua Chemical Co plant that killed 22 people on 28 November 2018, followed two smaller incidents in 2013 and 2014. A government inspection in 2015 revealed numerous problems with the plant’s chemical storage facilities and noted that the management’s approach to safety was at best inadequate.

The possibility of heavy fines of up to 100 million yuan (incidents involving more than 30 deaths can incur fines of 20 million yuan, though severe cases can mean that amount is doubled or even quintupled) encourages some business owners and local officials to collude to cover-up accidents and deaths when they do occur, especially in more remote areas where there are not many witnesses. Mine owners have been known to hide corpses and pay off victims’ relatives in order to ensure they keep quiet. Local government officials will often turn a blind eye to such subterfuge because reporting the accident to their superiors would only create trouble. On 10 January 2021, 10 people died in an accident at the Hushan Gold Mine in Qixia, Shandong. An investigation revealed that the company involved only notified the local authorities 30 hours after it occurred. See CLB’s report Bone and Blood: The Price of Coal in China for more details.

With the massive growth in the use of smartphones and social media however, it is becoming increasingly difficult for employers to hide or cover up accidents and work hazards. And, as we discuss below, workers themselves are beginning to take collective action to demand safer working conditions.

Tracking workplace accidents in China

The Chinese government’s official figures on workplace accidents present a generalised picture in which work safety is continually improving. The official picture is deliberately vague and opaque and lacks important details about the nature of workplace hazards, the most at-risk industries and the most common causes of death and injury. This lack of transparency prevents the public from assessing and understanding the real problem areas in work safety in China.

In December 2014, China Labour Bulletin launched a Workplace Accident Map to track and collate workplace accidents in China. The map is compiled using Chinese media reports and government records, using as a baseline for inclusion an incident with at least one worker death or impacting on three or more workers, either through injury or otherwise, for example, being trapped in a coal mine or forced to evacuate from a fire.

By the end of 2020, we had logged more than 3,200 incidents on the map. This is of course only a tiny fraction of the actual number of accidents but it is still sufficient to provide a qualitative and quantitative picture of workplace accidents and safety hazards across China. There is of course a sample bias caused by the reliance on official media and some extent social media reports. Coal mine accidents and incidents involving construction and sanitation workers for example are widely reported, while smaller incidents in factories and industrial facilities that occur within a contained environment are probably underreported.

The map also has a bias towards larger incidents that naturally get more publicity. Even so, 97.3 percent of all the accidents recorded on CLB’s Workplace Accident Map (where the death total could be confirmed) involved fewer than ten deaths, 2.3 percent of accidents had ten to 29 deaths, and only 0.3 percent (a total of nine) had more than 30 deaths.

The most common type of accident (as classified on the map) is a structural or mechanical failure, which accounts for 28.6 percent of the total. Around two thirds of these accidents occur in the construction industry, and typically involve the failure of lifting equipment (cranes, elevators etc.) or a scaffolding collapse. Because many workers are not properly tethered or sites lack the safety equipment needed to secure workers and material, such structural and mechanical failures often result in workers falling from a height or being hit by falling objects. In July 2018, the MEM confirmed what the Accident Map indicated, namely that the construction sector is the most dangerous industry in China and had been so for the last nine years. Moreover, accident and death rates had actually gone up in the first half of 2018, increasing by 7.8 percent to 1,732 accidents and by 1.4 percent to 1,752 deaths. The majority of accidents, the MEM said, were related to some kind of mechanical or structural failure and could have been avoided if proper safety procedures had been in place. In most cases, accidents result in a small number of injuries or deaths but the deadliest structural failure recorded on the map thus far occurred on November 2016 during the construction of a power plant in Fengcheng, Jiangxi, when a scaffolding tower collapsed killing 74 workers. Nine people including the company chairman and chief engineer were arrested soon after the collapse.

Construction workers are further handicapped by the lack of proper employment contracts and work-related injury insurance coverage in the industry. In the event of injury or death, it can be very difficult for workers to prove an employment relationship or, given the numerous different sub-contractors involved in any one project, determine who exactly is responsible for paying compensation. Injured workers can spend months, even years, seeking compensation and often only end up with a token payment that covers basic medical costs and no more. CLB argues in a report published in January 2019 that all construction workers need to be covered by a collective agreement that allows workers to be directly involved in the supervision and maintenance of health and safety issues at their workplace, and clearly states the measures to be taken in the event of an accident or death, thereby eliminating the need for workers to spend huge amounts of time and money on claiming compensation. This would of course first require a radical transformation of the trade union in order to negotiate such an agreement.

About 18 percent of accidents recorded on the map involve motor vehicles, and that proportion has been increasing in recent years as China’s cities expand and roads become more crowded. The vast majority of victims are either food delivery drivers or sanitation workers.

Sanitation workers often begin their jobs in the early hours of the morning when it is dark and drivers are not expecting to encounter people on the road. Other factors like icy roads and intoxicated drivers increase the risk of accidents, indeed, almost ten percent of all sanitation worker deaths are caused by drunk drivers. In one tragic example, five sanitation workers were killed and another two badly injured when they were hit by a car on a highway in the northern city of Harbin at five o’clock in the morning on 22 December 2017. The road was icy and the driver reportedly had a blood alcohol count of nearly twice the legal limit.

Many sanitation workers are elderly, making them more vulnerable to injury or death in the event of an accident. Elderly workers have an additional problem in that they often cannot claim injury compensation and their families cannot claim death benefits because they were beyond the statutory retirement age, as in the case of Wang Shoucun, a 70-year-old sanitation worker who was killed by a vehicle while on the job. The local government classified his position as a “service provider” with no formal relationship with the company he worked for and therefore not eligible for work-related injury compensation.

Unlike sanitation workers, the majority of food delivery workers are under 30 years-old, many are just teenagers, with little experience in riding motorcycles, e-bikes or scooters. They are also usually less risk-averse than older drivers. Many riders are not properly licensed or fail to obey traffic rules, making them ineligible for compensation if they are involved in an accident. There are of course some express delivery and food delivery workers who are middle-aged or elderly, many of whom were laid off from state-owned enterprises, and they face the same risks as elderly sanitation workers in terms of injury and lack of insurance.

While not as common as structural and mechanical failures or accidents involving motor vehicles, explosions and workplace fires usually involve far more casualties, cause far more damage, and attract far more attention and scrutiny than smaller accidents: 29.7 percent of explosions and 18.8 percent of fires recorded on the strike map involved more than ten fatalities. By far the worst accident in recent history occurred on 12 August 2015 when firefighters responded to a fire that had broken out in a warehouse in the Binhai port district of the coastal city of Tianjin. The firefighters doused the blaze with water, unaware that the warehouse was being used to illegally store hazardous materials, setting off a chain of explosions. 173 people died, including 104 firefighters, the youngest of whom was just 17 years old.

The Tianjin tragedy revealed the flagrant and widespread disregard for safety laws in China, particularly regulations pertaining to the storage of hazardous chemicals and zoning. In the aftermath of the blast, the government identified about 1,000 chemical production facilities that had been located too close to residential areas, and ordered their immediate closure or relocation. This, however, did little to stop major explosions. Just 11 days after the Tianjin explosion, there was an explosion at a chemical plant in Zibo, Shandong that killed one worker and injured nine others, and one week later, a chemical plant in the city of Dongying, also in Shandong, exploded killing 13 workers and injuring 25 others. More recently, on 21 March 2019, an explosion at a chemical plant in Xiangshui, Yancheng left 78 dead and 245 severely injured. On 13 June 2020, the explosion of an oil tanker in Wenling, Zhejiang, possibly the most serious accident involving a tanker over the last 20 years, left 19 dead and 172 injured. A year later, on 13 June 2021, a gas explosion in Shiyan killed 26 and injured 138.

According to map data, around a quarter of all explosions occur in the manufacturing sector. Accidents in this sector range from the explosion of heavy equipment like boilers or furnaces, to the combustion of volatile commodities such as fireworks and other explosives. Explosions most often occur when machinery is poorly maintained or misused or when factories are operating without a permit or exceed the scope of their capacity. For example, a fireworks factory in Henan that exploded in 2016 killing ten workers was operating illegally. The most deadly factory explosion in recent history occurred in August 2014 when at least 146 workers were killed in an explosion at an automotive components factory in Kunshan. In that case, the factory building was not properly ventilated, leading to the build-up of highly combustible dust particles.

There have been several large-scale factory fires over the last decade including the fire at a poultry processing plant in Jilin in 2013 that killed 119 workers. In nearly all major fires, exits were blocked, there was a lack of fire-fighting equipment and the workers had not received any training on fire prevention or what to do in the event of an emergency. In December 2018, a fire at another agricultural processing plant in Shengqiu, Henan, killed 11 workers.

Gas and chemical exposure is another very common hazard faced by workers in factories and industrial facilities. The best known case occurred in 2010 when scores of workers at a factory in Suzhou producing iPhones, among other products, were poisoned by the chemical n-hexane, which was used to clean touch screens. Workers complained of headaches, dizziness, weakness and pains in their limbs. At least 62 workers required medical care and several of them spent months in hospital. More recently, eight workers were killed and another ten badly injured in a gas leak at the Shaoguan Iron and Steel plant in Guangdong.

Repair and maintenance workers are also at risk from chemical exposure, usually due to the build-up of toxic gasses like methane in confined spaces such as sewers. In one typical example, in April 2016, a property management company subcontracted a sewer cleaning project to a company who sent a team of three workers to the job site. When one worker lost consciousness below ground, the other two attempted to rescue him but they too were overcome by the toxic gasses and all three died. As in many similar cases, the workers were unaware of the risks they were facing and lacked the protective equipment they needed. On 13 June 2021, the same day that a gas explosion in Shiyan, Hubei, killed 26 people, two employees responsible for maintenance at a mustard plant in Dayi, Sichuan, fell into the waste water tank to their deaths, with another four dying in a rescue attempt. It is likely that they were overcome by the toxic gas building up in the tank.

In May 2020, the United Nations International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) published a Chinese/English bilingual explainer on the rights of workers (globally and in China specifically) who are exposed to toxic substances. It includes a detailed breakdown of China’s current laws and regulations related to occupational health and safety. This was distributed to Chinese trade union leaders in the hope of enhancing the unions’ role in guaranteeing work safety.

Occupational health and safety

Occupational Illness

Chinese law recognises a broad array of occupational diseases, with ten major categories and 132 specific illnesses, outlined in the 2011 Occupational Illness Law and in the 2013 Categories and Catalogue of Occupational Diseases. Major categories include pneumoconiosis, radiation-related illnesses, poisoning, etc.

By far the most prevalent occupational illness in China is the deadly lung disease pneumoconiosis, which is caused by the long-term inhalation of mineral dust whilst working in mines, quarries, construction sites and mineral processing factories etc. However, workers with pneumoconiosis nearly always face an uphill battle getting their illness officially recognised as work-related because they cannot prove an employment relationship with a particular employer or that the disease was contracted at a time when they were employed there. A large proportion of mine and construction workers are rural migrants who do not have proper contracts and often only work at one location for a short period of time. Pneumoconiosis can take years to develop and victims are often unaware that they have contracted the disease until it is fully developed and incurable. As a consequence, only about ten percent of the estimated six million workers with pneumoconiosis have had their condition officially certified as an occupational illness.

Death from pneumoconiosis can be slow and painful, and hospital treatment is a major financial burden for workers and their families, often amounting to more than 100,000 yuan over the course of several years. Victims find it very difficult to find employment and have no option but to borrow money from family or even loan sharks in order to pay for medical treatment.

Most local governments are reluctant to pay workers with pneumoconiosis anything more than a basic charitable handout. As a result, workers have been forced to take collective action to get the work-related injury compensation they deserve. See Time to Pay the Bill: China’s obligation to the victims of pneumoconiosis

The Leiyang construction workers in Shenzhen, 2009

In the summer of 2009, 180 former construction workers from Leiyang in the southern province of Hunan travelled back to Shenzhen to demand compensation for the pneumoconiosis they had contracted working on the city’s construction sites in the 1990s. After a sustained campaign that gained considerable media attention, the Leiyang workers received a total of 14 million yuan in compensation, with individual pay-outs ranging from 70,000 yuan to 130,000 yuan depending on the severity of the illness. Within a few years however, nearly all the money was gone and the workers who were still alive were struggling just to get by. “I have spent almost all of the compensation and now I don’t know what to do. I have no real aspirations anymore. We just live from day to day,” worker Xu Zuoqing told a Chinese television documentary in 2013. Five years later, more workers and their families from the region arrived in Shenzhen to seek a long-term agreement on compensation that would cover all medical expenses and provide a small monthly stipend. The Shenzhen government eventually agreed to a deal but the Hunan government is reportedly still delaying the process.

Workers with pneumoconiosis who take collective action to demand compensation are often harassed and even detained by local authorities who view them as troublemakers. Workers from lead and zinc mines of Ganluo county in Sichuan had been trying for the best part of decade to get compensation when one of them was sentenced to ten days in administrative detention for trying to contact the provincial party secretary during a visit to Ganluo in 2016.

Factory workers have also taken collective action over occupational illness. In the summer of 2017, for example, 150 painters at a German-owned factory in Shenzhen demanded medical check-ups when the boss announced the factory’s closure and relocation. The workers had developed persistent headaches after working for years without any proper safety equipment. When the boss refused to give employees medical checks, or the compensation they demanded, around 2,000 workers went out on strike. Six months later, about one hundred workers at Eurotec Electronics in the nearby city of Zhongshan went on strike on 6 December in protest at dangerous working conditions. About 80 percent of the workforce had complained of dizziness, headaches, coughing, weakness and blurred vision after the factory relocated to a new facility in September. Workers bought their own testing equipment and soon discovered that levels of dangerous chemicals like formaldehyde were three to ten times higher than the recommended safe levels.

Dangerous living conditions

The use of traditional factory dormitories has declined dramatically over the last decade: In 2011, around half of all migrant workers lived in dormitories or on their job sites, and only 35 percent lived in rented accommodation outside the workplace, according to the National Bureau of Statistics annual report on migrant workers. In 2016, however, the same annual survey put the proportion of migrant workers living in rented accommodation at more than 60 percent, while only 13.4 percent lived in housing provided by their employer.

This change is partly explained by the closure of many old factories and the growth of employment opportunities for young workers in the service sector that do not provide accommodation. In addition, however, many factory workers now choose to live outside in order to have greater privacy and the chance to live together with family. On the downside, this also means higher rents, poor living conditions and often increased safety hazards.

Many old factory dormitories were themselves fire traps but living conditions for workers outside can be even more dangerous. The Daxing fire in the southern outskirts of Beijing that killed 19 people including several children on 18 November 2017 revealed the squalid and dangerous conditions that many workers now have to live in. The victims, many of whom worked in nearby garment factories, lived three or four crammed into a room of around ten-metres-square with no central heating despite night-time temperatures having already dropped to below zero.

Construction workers and miners very often have no choice but to live in whatever substandard dwelling their boss provides because there is no affordable accommodation anywhere near the work site. All too often, the accommodation provided puts them in a very vulnerable position. In August 2015, at least 65 migrant workers and their family members were killed when a massive landslide devastated a small jerry-built mining community in Shaanxi. On 1 December 2017, a fire broke out in the early hours of the morning at a building undergoing renovation in Tianjin. More than 20 workers were living on site and were caught in the blaze. Ten died, and five more were injured.

Very often, poorly paid workers in the service industry also have to endure substandard housing. In one tragic example, five young kindergarten teachers in a small town in Jiangxi died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty water heater in the 13-square-metre room they all shared. The young women were hired as interns and could not afford to rent an apartment by themselves so had to accept the onsite accommodation provided by the school.

Death and injury due to overwork

Serious physical and mental health problems stemming from overwork have been a long-standing issue in China. During the manufacturing boom of the 1990s and 2000s, factory workers often had to work excessively long hours to keep up with demand, leading to exhaustion, repetitive strain injuries and accidents related to lack of sleep. While factory overtime has gradually decreased as manufacturing growth slows, working hours in service industries and white-collar jobs, especially in the fast-growing tech sector, have increased.

Employees at major tech companies are very well paid by Chinese standards but are expected to work for as long as they are needed each day. Staff often cite the phrase “996” to describe their working life — starting work at 9.am, leaving at 9.pm and working six days a week. Most people feel they have no option but to comply. “There’s a huge number of candidates who can replace anyone in this field,” said a product manager in Shenzhen who used to work in the gaming industry. As a result, he said, “no one will bother to take any action against their employer or file a complaint. You just don’t want to cause any trouble.”

A 2018 survey by job recruitment website Zhaopin found that around 85 percent of white-collar workers in China had to work overtime, with more than 45 percent reporting overtime of more than ten hours a week. The overwhelming majority of Chinese citizens suffer from sleep disorders, for which pressure from work is a major factor, according to a 2017 report by the Xinhua news agency. Another report by the China Daily said more than 60 percent of Chinese citizens don’t get enough sleep, adding that this can cause long term health problems like cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression. Over half a million people die from heart attacks each year in China, and work-related stress is a major factor, according to a CCTV report; Dr. Zhang Fu of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences warned of the alarming increase in the number of young people that die from heart attacks, and linked these deaths directly to stress at work.

In recent years, a string of sudden deaths at tech companies have been linked to overwork culture. On 8 December 2018, a 25-year-old employee at drone company DJI died suddenly. While the company denied there was any overtime culture, people online said that programmers often worked until the early morning. On 3 January 2021, a 22-year old employee at e-commerce company Pinduoduo died after leaving work in the early hours of the morning. Just a few days previous, on 29 December 2020, another employee collapsed on her way home from work and later died. The company is known to make employees work for 13 days consecutively, without rest, for more than ten hours a day. On 6 May 2021, a programmer at iMyFone was found dead at home, after telling his family he suffered from tightness in the chest and headaches due to overtime. The rapid growth in e-commerce in China has led to massive increase in the workload of workers in the transport and logistics sector, particularly in periods of high demand just as Singles Day on 11 November each year. China’s estimated 30 million long-distance truck drivers often work 20 hour days for a month on end, nearly always sleeping in their cab. In December 2018, the deaths of a well-known truck driver couple on a 3,800-kilometre trip from their home in Henan to Tibet, highlighted for many the long hours and appalling working conditions that truckers in China have to endure.

Death from overwork, or karōshi to borrow the Japanese term, is reportedly widespread in China although statistics on the phenomenon are scarce and unreliable. A 2016 CCTV report stated that over 600,000 workers die from overwork each year. An estimate from a decade earlier in 2006 guessed that the number was over one million. The actual number of deaths in China directly attributable to overwork rather than a pre-existing condition may be impossible to calculate but it is clear that overwork is a widespread and serious problem and that the government has done little to tackle it. Some tech company bosses such as Feng Dahui, founder and chief executive of Nocode Technology, are belatedly realising that “overwork does not achieve better results” and are cutting down on employee work hours as a result but they are still very much in the minority.

Conclusions and recommendations

Workplace accidents for the most part involve just one or a handful of people and often go unnoticed by the public. Over the course of a year however they add up in the tens of thousands. Chinese government officials are clearly aware that work safety is a major issue; unfortunately, their focus still seems to be on the prevention of high-profile accidents rather than guaranteeing a safe environment of all workers on a day-to-day basis. In his address to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping stated:

We will promote safe development, and raise public awareness that life matters most and that safety comes first; we will improve the public safety system and the responsibility system for workplace safety; we will take resolute measures to prevent major accidents, and build up our capacity for disaster prevention, mitigation, and relief.

In a January 2019 press conference, the MEM downplayed the actual number of accidents and highlighted instead the fact that 2018 had been the first year since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 in which there had been no accident with more than 30 fatalities, or incidents classified by the Chinese government as accidents with an exceptional loss of life (特别重大事故).

In order to really improve work safety in China, and not just eliminate major accidents, there has to be greater enforcement of existing regulations. Government officials need to be proactive rather than reactive, and adopt a constructive, problem-solving approach to work safety rather than just slapping fines on business owners who are not in compliance. More importantly, there has to be a fundamental change in labour relations in the workplace so that frontline workers are encouraged to report safety hazards, employers are discouraged from forcing employees to work in a dangerous environment, and workers are properly cared for and compensated when accidents do occur. In particular, trade unions need to take up the supervisory responsibility assigned to them. They need to play a far more positive role in work safety rather than just providing “psychological consultations” and handing out post-disaster self-help handbooks to local residents, as the Tianjin Municipal Trade Union Federation did in the aftermath of the August 2015 explosions. In terms of systems design, trade unions should be supervising daily work, and be held responsible for accidents when they occur.

China Labour Bulletin recommends the following concrete measures:

- Ensure there is greater transparency on workplace safety so as to give policy makers, civil society and ordinary citizens the knowledge they need to assess risks and formulate remedial measures. National and local government statistics on workplace accidents and known hazards should be openly available to the media and the public without precondition.

- Guarantee formal labour contracts and work-related injury insurance for all workers, as required by law, so that in the event of injury, workers can prove they have an employment relationship and pursue claims for work-related injury compensation more easily.

- Introduce a worker-run health and safety committee in all workplaces, with directly elected representatives who can monitor and remedy known work hazards and ensure that the employer is in compliance with the law.

- Ensure that there are democratically-elected and democratically-run trade union branches in all workplaces, especially in new service industries that rely on flexible labour. This would give trade union officials, who are too often isolated in their regional offices, a much greater connection to ordinary workers.

- Once established in the workplace, trade unions should make work safety a top priority. Union officials should ensure that employees are properly trained and have the safety equipment they need to perform their assigned tasks. They should encourage workers to raise safety concerns, report workplace hazards, and protect whistle-blowers from management reprisals. Once hazards are detected, the trade union should act immediately to rectify the situation, and demand that production be shut down if necessary.

- Outside the workplace, the government should take action to tackle the dangers associated with substandard housing. Local governments should build affordable housing for low-income working families. In addition, local governments need to relax the restrictions on access to education, healthcare and social services for rural migrant workers. These obstacles add to the already considerable financial burden of living in major cities and force migrant workers to accept potentially hazardous accommodation.

In the three decades since the infamous Zhili Toy Factory fire in Shenzhen in 1993, which killed 87 young migrant women workers and injured 47 others, the government’s approach to work safety has remained basically the same: Reacting to major disasters with heavy-handed and coercive measures that do little to get to the heart of the problem or create a genuine safety culture in the workplace.

Accident and death totals have declined from the horrific peaks of the early 2000s, however that has as much to do with economic factors as government policy. If China is to create a truly safe working environment, then a fundamental change is needed in government policy, labour relations and the role of the trade union.

This article was first published in January 2018 and was amended in September 2021.