For the Chinese version of this article and additional links to Chinese language sources, please see 中国的社会保险体系 on our Chinese website.

Introduction

China has achieved remarkable economic growth and development over the last four decades, but it has so far failed to create a comprehensive social welfare system that can protect and support workers in old age and ill-health and provide relief in times of economic distress. As China enters the fifth decade of the reform era, the social welfare system is looking increasingly fragile. The population is ageing, fewer people are entering the workforce, and there are real concerns that the funds needed to support the welfare system could be entirely depleted unless radical reforms are introduced in the near future.

The current problems in China’s social welfare system can be traced back to three key processes: The break-up of the state-run economy, which had provided urban workers (a relatively small proportion of the overall workforce) with an “iron rice bowl” comprising guaranteed employment, housing, healthcare and pension; the mass migration of rural workers (with no welfare coverage) to the cities; and the one-child policy introduced in the 1980s, which meant that parents could no longer rely on a large extended family to look after them in their old age.

To fill the social welfare vacuum that began during the early stages of the reform era, the government sought in the 1990s to create a new system based on individual employment contracts that would make employers - and to a lesser extent, individual employees – primarily responsible for contributions to state-backed pensions, unemployment and medical insurance schemes. Local and regional governments, rather than the national government, were to administer these funds.

The new system emerged piecemeal through a series of regulations and provisions in the 1994 Labour Law (劳动法) and 2008 Labour Contract Law (劳动合同法). It was not until 2011, however, that these separate parts were codified into a comprehensive national framework in the Social Insurance Law (社会保险法).

All employees, including rural migrant workers, were supposed to be covered by the new social insurance system. But, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2020, the state’s basic pension plan covered only about 71 percent of the urban workforce, and only 47 percent had unemployment insurance. The coverage rate for medical insurance was slightly higher than pension coverage but, as documented below, the healthcare system is riddled with problems, and patients still have to pay up front for hospital care before they can claim reimbursement.

The lack of social insurance coverage stems from the failure of enterprises, small- and medium-sized enterprises in particular, to provide employees with their legally mandated benefits. The initial employer contribution rates set by the government were relatively high, and many private companies balked at the cost. Local governments, anxious to attract investment, turned a blind eye to non-payment. Rather than enforce the law, the authorities gradually reduced the contributions employers had to pay.

At the same time, the government is encouraging those not covered by the state’s primary plans to take up urban and rural residents’ pension and medical insurance schemes, which are based on individual contributions and subsidised by the government. This allows the government to claim that the vast majority of residents are covered by social insurance. However, as we discuss below, the benefits payable under these residential schemes are very limited.

Here follows a detailed look at the current state of the pension system, then medical, maternity, unemployment and work-injury insurance, and the challenges ahead both for the government and ordinary workers.

Job seekers outside a recruitment office in Dongguan

The pension system

The basic framework for China’s state pension system was set up in 1997 under the State Council Decision on the Establishment of a Unified Basic Pension System for Enterprise Workers (国务院关于建立统一的企业职工基本养老保险制度的决定). Both employees and employers are required to make contributions to the pension system. Workers contribute based on their individual wage, at a rate of up to eight percent, while employers contribute a percentage of the total wages paid to their workforce, initially around 20 percent. For decades in China, there was a separate pension system for civil servants and other government employees such as teachers, who did not need to pay their own pension contributions and were entitled to a generous government-subsidized pension on retirement. However, in January 2015, the State Council in its Decision on the Reform of the State Employee Pension System (国务院关于机关事业单位工作人员养老保险制度改革的决定) introduced a new pension plan designed to equalize the private and public sector systems. Under the new scheme, public sector employees make their own contributions to the pension fund. However, the authorities have stated that the basic salaries and pension benefits of civil servants and employees of public institutions will be augmented accordingly to offset any financial losses for employees under the new system.

There is a cap on contributions for both employers and employees, but exact contribution rates vary from region to region. In mid-2016, several provinces and cities, including Beijing, started to reduce employer contributions from 20 percent to 19 percent, and some regions such as Guangdong later reduced rates to as low as 14 percent. In 2019, Premier Li Keqiang formally announced in his work report to the National People’s Congress that employer contribution rates in all regions could be reduced to 16 percent, as part of a package of measures designed to relieve the tax burden on businesses. In 2020, at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, companies enjoyed exemptions from paying social security contributions. Employers were allowed to stop contributions to pension funds, unemployment insurance, and work-injury insurance for up to six months. That year, enterprises saved 1.54 trillion yuan from these measures, with pension fund exemptions making up 1.33 trillion yuan of that total.

The urban/rural pension divide

The urban employee pension plan combines a “social pension” with a “personal account.” During the period of employment, employer contributions fund the social pension, while the employee’s contributions are paid into the personal account. On retirement, the balance of the personal account, including interest, is divided into 139 instalments to be paid out monthly over a ten-year period. In addition to the benefits paid out from the personal account, the worker also receives general pension payments, payable until death. The general pension payments are determined by the number of years of employment, the average wage in the locality, and average life expectancy. These general pension payments are ostensibly funded by the employer’s contributions, but the government is legally obligated to cover any shortfalls.

Workers become eligible for pension benefits when they reach the statutory retirement age, but only if they have participated in the scheme for at least 15 years. Those who have participated for less than 15 years may delay retirement until they have contributed for 15 years, pay the remaining required contributions, transfer their pension plan to a plan for non-employed rural or urban residents, or receive the entirety of their individual account, including interest, in a lump sum payment.

For several years now, the government has been promoting a pension for urban and rural residents who are not covered by the urban employee scheme. This supplementary scheme requires residents to pay contributions into an individual account for at least 15 years before becoming eligible for a pension on retirement. After China launched its campaign on extreme poverty alleviation, the government began to make contributions into this fund for more than 60 million poor citizens, starting in 2017. By the end of 2020, around 30 million previously impoverished people who had reached the age of 60 started to receive benefits from this fund.

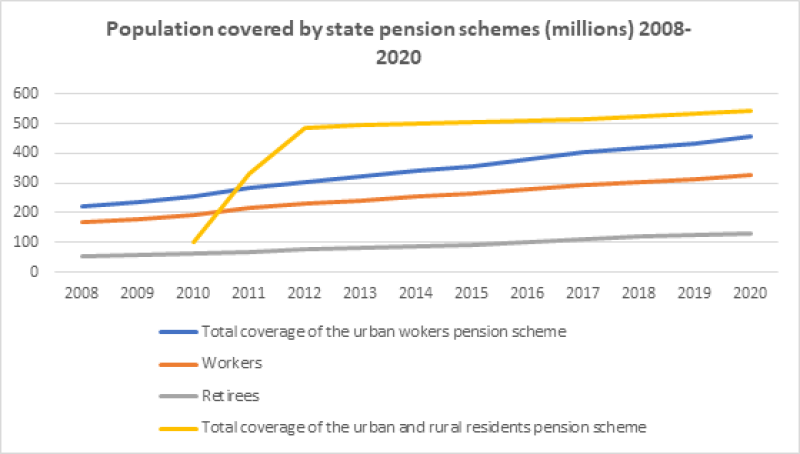

There are serious disparities in the benefits paid out by the urban employee pension plan and the supplementary urban and rural residents’ pension scheme. About 542 million people are covered by the urban and rural residents pension scheme, with 161 million currently receiving payments. In 2020, 335 billion yuan was paid out under the scheme, equivalent to just 174 yuan for each person per month. This is not enough for someone to live on in even the smallest villages. In comparison, the urban employee pension plan paid out 5,130 billion yuan to retirees in 2020, with 128 million of them receiving around 3,350 yuan per month (around 70 percent of the average salary received by employees in private companies in urban areas). This is usually more than sufficient to cover basic living needs.

As of the end of 2020, the number of people covered by both state pension plans reached 998 million, but 54.3 percent were covered by the supplementary urban and rural pension scheme. The number of people covered by the urban employee pension plan reached 456 million, of which the number of insured employees (329 million) accounted for about 71 percent of all urban employees. Hundreds of millions of workers are still not covered. Most of them are migrant workers and those in flexible employment.

Data source: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security

Migrant workers have always made up a low proportion of those enrolled in the basic urban pension plan. The number of rural migrant workers covered by the urban employee pension plan in 2017 was estimated at just 62 million, or about 22 percent of the total migrant worker population at the time. At the end of 2020, there were 285 million migrant workers in China, accounting for about 36.8 percent of the employed population, but most of them were not included in urban employee pension plans or were only part of medical insurance schemes for urban and rural residents. The government has not released any official figures on coverage rates since 2017.

Article 95 of the Social Insurance Law stipulates: "Rural residents who enter cities for work shall participate in social insurance in accordance with the provisions of this law." The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security has also emphasized that place of hukou registration should not restrict migrant workers from being covered by urban employee pension plans.

In reality, many companies ignore their legal obligations to pay social insurance for each employee and do not pay social insurance, including contributions into pension plans for migrant workers. Driven by concerns about economic development, local governments have long refrained from investigating non-payment, so enterprises rarely face penalties. Many migrant workers have worked for well over 15 years in cities, but there is no record that any social insurance payments have been made on their behalf. Once they retire, they can transfer the social insurance relationship to where they have hukou registration and then either make up the shortfall themselves and perhaps come to an agreement with previous employers, depending on local regulations and their personal circumstances, or enter the urban and rural resident pension system. See Migrant Workers and their Children for more details.

The rise of the gig economy and flexible employment has further eroded pension protection. Official reports estimate that there were 200 million people in flexible employment in 2020. And a report by Renmin University’s School of Labour and Human Resources estimated that some form of flexible employment accounted for 56 percent of total employment in 2020, an increase of about 11 percentage points from 2019. Workers in the gig economy usually do not sign formal labour contracts, and most companies do not make social insurance payments on their behalf. They, like migrant workers, will face difficulties trying to secure an old age pension. For example, they might have made contributions in multiple jurisdictions but might not meet the 15-year requirement in one specific district. Alternatively, their employer may have treated them as a service provider rather than an employee and refused to pay into the urban employee scheme. In either case, they will find it difficult to provide for themselves in their old age and have a decent retirement.

The demographic threat

One of the biggest problems with the current pension system in China is the statutory retirement age: 60 years for men; and 50 years for women workers in enterprises, or 55 years for women civil servants. These limits were established in the 1950s and are no longer realistic in a country where the average life expectancy is now about 75 years, and around 12 percent of the population are already over 65 years.

The government has long acknowledged this problem, and officials have announced various plans to gradually increase China’s statutory retirement age. In March 2018, for example, the vice minister of Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Tang Tao, said the government’s aim was to raise the retirement age for women by one year every three years, while the retirement age for men would increase by one year every six years, so that by 2045 the retirement age for both men and women would be 65. However, up until now there still are no definitive regulations in place on raising the retirement age. The government said in March 2021, that it would “gradually postpone the legal retirement age” over the next five years, but again offered no further details.

In June 2021, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security issued its 14th Five Year Plan, which proposed extending the minimum contribution period for basic pension schemes beyond the current 15 years. Specific policies have yet to be announced, but there is speculation that, in order to make the fund viable in the future, the higher contribution period will have to be between 20 and 30 years.

China’s declining workforce and rapidly ageing population has heightened concerns over the future sustainability of the basic urban pension fund with one prominent report predicting that total expenditure will begin to exceed contributions in 2028 and that reserves will decline exponentially after that, leading to the complete depletion of the fund by 2035.

Currently, revenues for the basic urban pension fund still exceed expenditures in many provinces, particularly those with a high proportion of younger workers like Guangdong, which in 2019 had a healthy yearly surplus of 183 billion yuan and an overall balance 1,234 billion yuan - by far the highest balance of any province. However, even in Guangdong the yearly surplus in 2019 was 39 billion yuan lower than the previous year. Provinces in the centre and northeast of China with many retirees and a shortage of young people are already feeling the strain. In Heilongjiang, for example, pension pay-outs exceeded revenue by about 31 billion yuan in 2019, up from a deficit of 16 billion yuan in 2018. As a result, in July 2019, the central government embarked on a regional pension redistribution plan, which collected 485 billion yuan from seven richer provinces and redistributed the funds to 21 poorer regions that had seen significant outflows of labour. Nevertheless, Heilongjiang still had an overall account balance of minus 43 billion yuan compared with minus 55.7 billion yuan in 2018, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. The amount of funds redistributed in 2020 increased by four percent to 740 billion yuan.

Ideally, there needs to be a single unified national pension fund. However, while some individual provinces have successfully pooled local funds, significant differences in regional development, local fund imbalances, and contribution and payment rates means that creating a national system that covers everyone, including migrant workers and the informally employed, will be extremely difficult.

In 2020, the government announced the development of what it called a new “multi-pillar pension system.” The second pillar (after the basic urban pension and urban and rural resident pension schemes) was to be a corporate and occupational annuity fund. Under this scheme, both the employer and worker pay annuity, the total of which should not exceed 12 percent of the worker’s total wages. This aims to maximise contributions so that employees can enjoy a larger pension through the annuity. So far, however, only companies that can guarantee higher returns have set up annuity schemes. As of end 2020, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security reported that a total of 105,000 companies had established a corporate annuity scheme, covering 27 million employees, or just 3.5 percent of the total employed population.

Housing Provident Fund

The Housing Provident Fund is not officially part of China’s social insurance system. It is administered by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development rather than the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. However, it is often grouped together with the original five official social insurance programs since it functions in a similar manner, with benefits funded through contributions paid by employers and their employees.

The fund was first established in 1999, a time when state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were laying off tens of millions of workers. The government could no longer rely on SOEs to meet the housing needs of workers, so the Housing Fund was promoted as a means by which employees could pay for and maintain their own home. Contributors to the housing fund can apply for preferential rate mortgages, cover housing repair and maintenance costs and receive rent subsidies. If unused, the fund can be redeemed upon retirement, and so it actually functions more as a secondary pension. In addition, recent local amendments have allowed housing funds to be used for non-housing related expenses such as urgent or serious medical treatment costs.

The Regulations on the Administration of Housing Funds (住房公积金管理条例) state that local governments determine employee and employer contribution rates, but these should not be lower than five percent of the average wage at the enterprise. In Beijing, for example, employers have to contribute 12 percent of the average wage during the previous year and employees contribute 12 percent of their monthly salary. In Shanghai, employers contribute seven percent of the average wage during the previous year and employees contribute seven percent of their average monthly salary in the previous year. In all cases, however, contributions are made on a monthly basis and are tax-deductible.

Traditionally, it has been state-owned enterprise employees, government workers and public servants such as teachers who were the main contributors to and beneficiaries of the housing fund. The number of workers contributing to the housing fund remained stable at around 100 million from the mid-2000s until 2014 when both the number of employees and employing units suddenly increased. There were 2.1 million employers and 119 million employees enrolled at the end of 2014. In the six years to the end of 2020, however, the number of employers rose to 3.65 million and the number of workers grew by 34 million to 153 million. The sudden growth was almost entirely driven by private businesses and urban professionals looking for a way onto the property ladder. In 2014, about 60 percent of all enrolled workers were employed in SOEs or public institutions. By the end of 2020, employees of privately-owned and foreign-owned enterprises were in the majority. In all, 75 percent of the new accounts opened in 2020 were employees of privately-owned and foreign-owned enterprises.

For most low-paid workers, however, buying a property in the city remains a distant dream. For example, according to the government’s official survey of migrant workers, in 2018 the majority of migrant workers (61.3 percent) lived in rented accommodation, 19 percent purchased their own home, and 12.9 percent lived in accommodation provided by their employers, such as factory dormitories. In the vast majority of cases, migrant workers and their families are excluded from public housing. In larger cities, many migrant workers can only afford to rent small apartments in poorly constructed or dilapidated buildings in remote parts of the city, and even these dwellings can take up a sizable proportion of their monthly salary. Nevertheless, if they are enrolled in the housing fund, migrant workers can sometimes use it as a secondary lump sum pension, but numerous bureaucratic obstacles often get in the way of actually securing these funds.

Health insurance, maternity and childcare

The framework for China’s employee medical insurance system was first set out in the 1998 State Council Decision on the Establishment of a Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban Staff and Workers (国务院关于建立城镇职工基本医疗保险制度的决定). Under this regulation, both workers and employers must make payments to the basic medical insurance scheme which, like the pension scheme, comprises an individual account as well as pooled funds. Though the amounts vary from region to region, workers typically contribute two percent of their individual wages - all of which goes directly to their individual account - while employers usually contribute around six percent of their workforce’s salary. Employer contributors are included in the pooled funds while worker contributions go to individual accounts. Once the worker has paid into the system for the requisite number of years, they are eligible for benefits without having to make additional contributions.

The medical insurance fund pays for general outpatient expenses, treatment of serious illness and hospitalisation. Different regions have different regulations on minimum and maximum payment amounts and reimbursement ratios for employee medical insurance. In April 2021, a new round of reforms improved accounting methods and defined the scope for using individual accounts. In the past, a proportion of employer contributions (usually 30 percent) went into the workers’ individual accounts while the remainder went to the public fund. After the April 2021 reforms, all employer contributions now go to the pooled insurance funds. Workers are now able to use their individual accounts to cover medical treatment for family members. But in 2020, the per capita cumulative balance of individual accounts stood at just 2,919 yuan.

The Social Insurance Law stresses that the medical insurance fund should cover workers’ medical costs by paying service providers (usually hospitals and clinics) directly. However, in most cases, workers have to pay up front and request reimbursement from the authorities later. Moreover, to be eligible for public insurance funds, hospital treatments must be on a pre-approved government list; treatments outside of the pre-approved list must be paid out of either the worker’s individual account or their own pocket. Coverage for outpatient treatment and medicines is even more limited. This means that people who need outpatient treatment and medicine often have to buy additional private medical insurance, pay for treatment out of their own pocket or forgo treatment altogether.

Employee and residents’ medical insurance schemes

In the past ten years, the number of employees and retired employees covered by the basic medical insurance for urban employees has increased steadily. According to the Statistical Bulletin of Medical Security Development in 2020, as of the end of 2020, the number of people participating in basic medical insurance for employees in China was approximately 340 million. However, similar to the situation of pension insurance, the coverage of employee medical insurance for migrant workers and flexible employment groups is still limited. It is estimated that the number of migrant workers with basic medical insurance in 2017 was only 62 million, accounting for about 22 percent of the total number of migrant workers at that time.

Given the limited coverage provided by the urban basic medical insurance plan, the government has heavily promoted supplementary medical insurance schemes for urban and rural residents (城乡居民基本医疗保险), including the self-employed, casual workers, non-working spouses, the elderly and children. In December 2016, the State Council issued Opinions on Integrating the Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban and Rural Residents, calling for merging urban and rural resident medical insurance with the new rural cooperative medical insurance scheme into a unified insurance scheme. In March 2018, the National Medical Security Administration was established as part of government institutional reform. At present, the medical insurance system has been merged into a two-track system that consists of Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (hereinafter referred to as “employee medical insurance”) and Urban and Rural Residents' Basic Medical Insurance (hereinafter referred to as “residents’ medical insurance”).

By the end of 2020, more than 95 percent of the population (1.36 billion) had some form of medical insurance. About 75 percent of those covered (1.02 billion people) participated in the residents’ medical insurance scheme, while 340 million were covered by the employee medical insurance program. Of those covered by the employee scheme, 27 percent (90.25 million) were already retired.

Data source: National Healthcare Security Administration

While the coverage of the residents’ scheme looks impressive, the benefits provided are very limited. The urban and rural residents’ medical insurance schemes paid out only around an average of 798 yuan per person in 2020, which is barely enough to get in the door of a major hospital. The main urban worker basic medical insurance fund, on the other hand, paid out an average of 3,730 yuan per person. In 2019, per capita hospitalisation expenses reached 9,848 yuan, far exceeding per capita benefits paid out from either insurance scheme.

There are significant regional differences in the level of expenditure from employee insurance schemes. In the national capital of Beijing, which has some of the country’s most expensive healthcare facilities, per capita expenditure on employee medical insurance was around 5,984 yuan per person in 2018, far exceeding the national average. In the north-eastern province of Jilin, which has a higher concentration of elderly, per capita expenditure was 2,579 yuan. In Guangdong, which has a higher working age population, it was 2,392 yuan.

There is also a massive disparity between urban and rural areas in terms of healthcare resources. On average, the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people in most cities is twice that of rural areas. Doctors in rural areas face extreme work pressures, heavy workloads and low pay. At the end of 2019, there were only 792,000 village doctors nationwide. Data from the last five years shows that the number of village doctors has dropped sharply at an average annual rate of 50,000. In 2019, for example, doctors from villages in Henan, Heilongjiang, etc., collectively tendered their resignations in a bid for higher pay.

Given the income gap between urban and rural residents, the disparity in social security coverage, and the allocation of medical resources, rural residents are at an absolute disadvantage when it comes to access to medical services. The situation is so unbalanced that some scholars have argued that low-income groups are actually subsidizing the medical care of higher-income groups.

The merger of medical and maternity insurance

Maternity insurance was original separate from medical insurance and was one of the so-called “five social insurances.” Pilot projects to merge employee medical and maternity insurance got underway in 12 cities in 2017, and those jurisdictions subsequently reported a 13 percent increase in maternity insurance coverage. The Opinions on Comprehensively Promoting the Consolidation of Maternity Insurance and Basic Medical Insurance released in 2019 announced that mergers would continue nationwide, and the merger process is currently ongoing. The government claims the merger will simplify the contribution process for employers and not place any additional burden on employees, while maintaining existing benefits for mothers and their spouses.

Maternity insurance covers all maternity-related medical costs, including birth control, prenatal check-ups, delivery and antenatal care, as well as allowances to be paid during maternity leave. Women who are not covered by maternity insurance can be reimbursed for part of their maternity medical expenses in accordance with the medical insurance reimbursement rules.

According to the Special Provisions on the Protection of Female Employees (女职工劳动保护特别规定), which went into effect on 28 April 2012, women are entitled to 98 days (14 weeks) of maternity leave at a rate equal to at least the average wage at her employer. Some local governments require employers to provide additional allowances for employees earning more than the average wage. Although there is considerable regional variation, China’s maternity leave benefits are basically in line with the standards recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Following the introduction of the two-child family planning policy in 2015, various local governments established incentives to working mothers, including extending maternity leave anywhere from an additional 30 days to 267 days. There is considerable disparity in the benefits offered between regions and it remains difficult, even after the merger of medical and maternity insurance, for women to claim benefits.

Women who do not comply with family planning policies or do not have employee medical insurance cannot enjoy any benefits. Women in informal employment, without stable employment, or who are migrant workers are usually left without support. In 2019, official figures show that 214 million workers were covered by maternity insurance nationwide, of which an estimated 4.3 million women gave birth, and 3.5 million received maternity allowances. However, there were 14.7 million births that year. From this, we can see that less than one-third of women who give birth are covered by maternity insurance and even fewer received those benefits.

China’s ageing population and the decline in fertility rates led the government to amend the two-child policy in May 2021, allowing married women to have three children. However, this new policy could lead to even greater gender discrimination in the job market. Already, women are often asked about their family plans and are sometimes forced to sign illegal contract conditions that require them to take pregnancy tests or guarantee that they will delay pregnancy or not get pregnant at all. Many employers find ways to coerce pregnant workers into resigning by making them work unreasonably long hours or assigning them heavy or dangerous workloads. Other employers simply refuse to grant maternity leave and then fire employees on the grounds of absenteeism. More and more women are now taking legal action against such blatant rights violations. However, for most women, especially low-paid factory workers, going to court or even labour arbitration is simply not an option because they cannot afford the time and money to do so. See our section on Gender Discrimination under our Workplace Discrimination topic for a more in-depth discussion of this issue.

Unemployment and work-related injury insurance

The State Council’s 1999 Regulations on Unemployment Insurance (失业保险条例) established a framework for contributions to and payment of unemployment insurance that was largely affirmed by the Social Insurance Law in 2011. Both workers and their employers pay into the unemployment insurance system, originally at rates of one and two percent, respectively. However, many provincial and municipal governments have substantially cut contribution rates as a means of reducing costs for businesses. In Guangzhou, for example, the employer rate dropped from 1.5 percent to 0.8 percent, and the employee rate was cut from 0.5 to 0.2 percent, effective 1 May 2016.

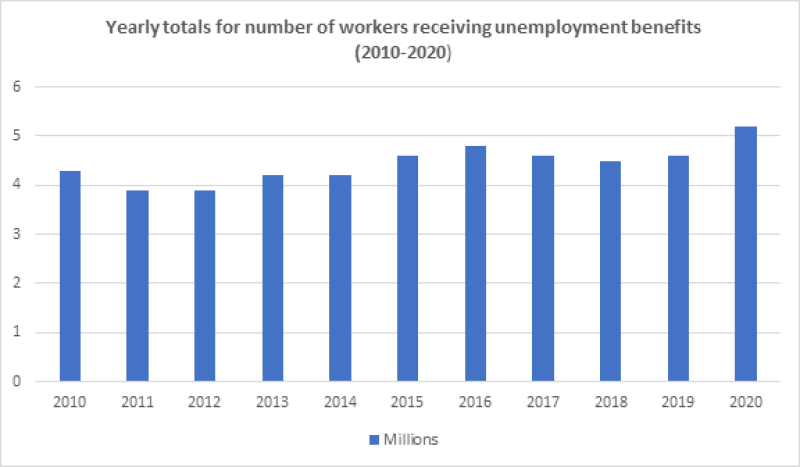

If workers and their employers have paid into the fund for the requisite number of years, they are entitled to apply for benefits when they become unemployed. The number of workers obtaining unemployment benefits each year has increased slightly over last decade (see chart below), but cost cutting by employers and lax enforcement of unemployment insurance regulations by local governments has meant that still only a small proportion of the total working population receive payments. There were 217 million workers covered by unemployment insurance in 2020, less than half the total urban workforce of 462 million. Throughout the year, benefits were paid to just 5.2 million workers. At the same time, the average urban unemployment rate in 2020, based on official surveys, was 5.6 percent, equivalent to about 26 million workers. And this figure does not take into account tens of millions of workers who were under-employed or on unpaid leave because of the Covid-19 pandemic that year.

Data source: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security

Moreover, although employee contributions are based on salary level, the benefits paid out are low. The 1999 Regulations state that unemployment benefits must be lower than the local minimum wage, which is already set at a very low level and is not a living wage. In 2020, the monthly average for unemployment insurance benefits was 1,506 yuan per person, lagging far behind the cost of living in major urban areas. See our section on Employment and Wages.

Although the Social Insurance Law stresses that unemployment benefits are transferable and can be claimed in any location, structural reforms will be necessary for this to become a reality, especially in rural areas that have no system for disbursing urban unemployment benefits. At present, many local authorities address the issue by providing migrant workers with a one-time payment far below the amount they are legally entitled to.

Unemployment insurance funds are often reassigned for job creation or job training projects rather than being paid to workers directly. In March 2019, for example, the government pledged to “allocate 100 billion yuan from unemployment insurance funds to provide training for over 15 million people upgrading their skills or switching jobs or industries.” The unemployment insurance fund had an overall balance of 581.7 billion yuan at the end of 2018.

Work-related injury, occupational disease

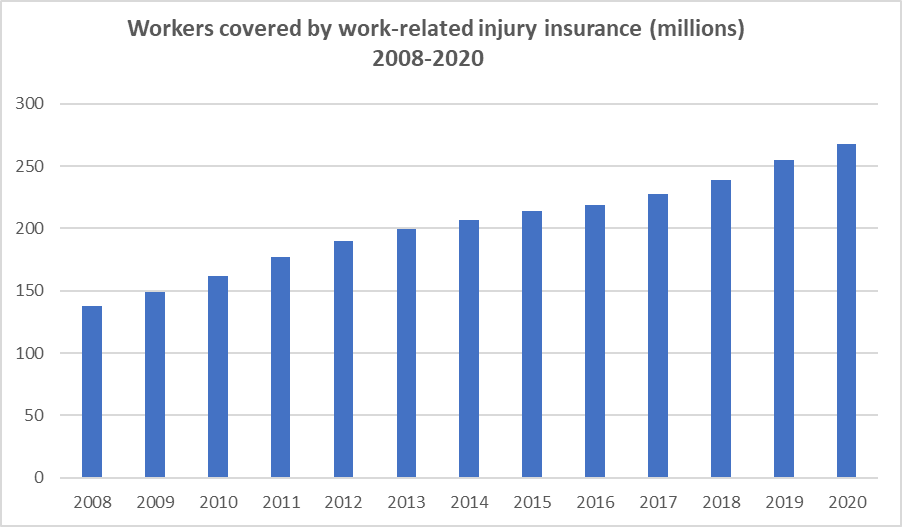

As with other forms of social insurance, work-related injury insurance coverage has increased steadily over the last decade, according to official statistics (see chart below). By the end of 2020, there were 268 million workers with work-related injury insurance. In China’s most dangerous industry, the construction sector, 98 percent of all workers had work-related injury insurance by the end of 2020.

Data source: National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security

Contributions to the work-related injury insurance fund are paid solely by the employer at rates of between 0.5 percent and two percent of payroll, varying according to the health and safety risks of specific industries and locations.

Workers are eligible for work-related injury compensation if they can prove they have a formal - or in some cases a de facto - employment relationship with their employer and that the injury sustained is in fact work-related. This is often a far from a straightforward process. Once a work-related injury has been confirmed, however, the local authorities assess the level of work disability on a scale from one to ten, with one being the most serious.

Workers suffering serious injuries are entitled to considerably more compensation than those with relatively minor injuries. The exact amount of compensation to be paid, and - importantly - the responsibility for paying it, are largely determined by the Social Insurance Law, the Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations and the Law on the Prevention and Treatment of Occupational Diseases. However, local implementing regulations and selective enforcement of certain provisions mean that the actual pay out varies considerably from region to region. Moreover, disputes between the employer and employee and the local authorities over the level of compensation and who should pay are a regular occurrence. If an employer fails to pay the required work-related injury insurance contributions, they are legally obliged to cover all expenses themselves. However, in most cases, delinquent employers refuse to pay anything more than basic medical costs for the time the employee is in hospital, if that. In 2020, there were 1.98 million beneficiaries of the work-related injury compensation fund who received 82 billion yuan in total, or 43,617 yuan on average, according to official statistics.

Occupational disease cases are particularly difficult for workers to resolve because the disease often manifests after the worker has already left their place of employment, and migrant workers in particular are unlikely to have a contract with that employer anyway. There are an estimated six million workers in China with the deadly lung disease pneumoconiosis, but only about ten percent of them have ever been certified as having an occupational disease. See CLB’s research report Time to Pay the Bill: China’s obligation to the victims of pneumoconiosis for more details.

The rise of the gig economy and increased use of flexible employment has eroded social insurance coverage in general, and work-related injury protection is particularly vulnerable. Large numbers of workers have no contractual relationship with the companies that rely on their labour, and they face considerable difficulty when they claim compensation for work-related injuries. This state of affairs is particularly serious in the logistics, food delivery, and transport services industries, in which about 84 million people were employed in 2020.

Current regulations make it difficult, if not impossible, for workers to claim work-related injury compensation. Accidents occur on a daily basis and, in most cases, workers struggle for any kind of compensation. In the first half of 2019, for example, there were 325 accidents involving express delivery and food delivery workers in Shanghai, which resulted in five deaths and 324 injuries. In one case where a delivery driver died on the job, for example, the court ruled that since the conditions listed in the platform registration agreement stated that there was no employment relationship between the company and driver, the worker was not entitled to work-related death compensation.

Conclusion

After China embarked on its much-vaunted economic reform and development program, the government gradually abdicated its authority in labour relations to business interests. As the private sector expanded, employers could unilaterally and arbitrarily determine the pay and working conditions of their employees, keeping wages low and benefits largely non-existent. The national government sought to protect worker interests by implementing legislation, such as the 1994 Labour Law and 2008 Labour Contract Law, but local governments either could not or would not enforce the law in the workplace.

Under these circumstances, creating a system where employers are primarily responsible for their employees’ social security was set to fail. Employers could often simply ignore their legal obligations and continue with business as usual, often with official connivance. After the 2008 financial crisis, for example, the central government allowed struggling companies to delay social insurance contributions for up to six months. The policy was never formally rescinded. It was only when the workers themselves started to demand payment of social security (most notably in the 2014 Yue Yuen strike) that employers were forced to comply. Then again, during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, employers were given another six-month social insurance contribution holiday as part of a four trillion yuan tax relief package for struggling enterprises.

The failure of the government to enforce the law and create a social security system that covers everyone has not only disadvantaged China’s workers, but severely hampered the government’s own ability to push ahead with and accomplish other important policy goals.

One of the key policies regularly enunciated by the government over the last few years has been to boost domestic consumption to ensure more stable and balanced economic growth in the future. Much of China’s consumption power, however, remains in the hands of the wealthiest one percent, leading to huge capital outflows rather than increased domestic spending. The majority of workers are still reluctant to spend because, lacking a pension or medical insurance, they tend to set aside what they can in bank savings and other riskier investments in order to try and secure their future and shield themselves from adversity.

The fact that only a fraction of the social insurance contributions that should have been made over the last two decades or so have actually been made means that the various social insurance funds are under much more pressure than they should be. With China’s rapidly aging population, this is a particular problem for the pension funds and medical insurance funds.

The government now accepts that it needs to increase the retirement age and implement wide-ranging reforms to have sufficient funds for expected pension and medical expenses in the future. However, the authorities are still reluctant or unable to force employers to comply with existing social insurance obligations. Rather, the government is trying to reduce the social insurance burden faced by employers and shift the burden of pension and other social insurance contributions onto individual workers, whether they be formally employed or not.

Instead of running away from the problems of the social insurance system, the government needs to accommodate the competing interests of labour and capital and create a realistic and stable social security system: one that looks after workers during poor health and old age, but also helps to create a content and well-paid workforce that can help develop the domestic economy through greater innovation, productivity and consumption of goods and services.

This article was first published in August 2012. It was last updated in August 2021.