The sudden closure of two major interior design chains, Apple 2003 and Yihao Jiaju, has sparked a new wave of protests over the last few weeks in which customers, suppliers and employees across China got together to present their grievances and demands to the failing companies.

Employees who found themselves suddenly out of a job and owed wages staged protests in at least a dozen cities, including: Changsha and Hengyang in Hunan, Hangzhou and Ningbo in Zhejiang, Shangrao in Guangxi, Wuhan in Hubei, Bengbu in Anhui, Fuzhou in Fujian, Xi’an in Shaanxi, Suzhou in Jiangsu, as well as Chongqing and Shanghai.

Apple 2003 employees stage protest in Fujian

Former employees, customers and suppliers of Apple 2003 created an online national network in late April, whose membership is still growing. It is unclear if more shops will cease operations in the near future, but as the news of closures spreads around the country, it is reasonable to think that similar protests may erupt.

This latest wave of nationwide worker protests follows the Lalamove van drivers’ collective action in protest against pay cuts and the tower crane operators’ Labour Day strikes in an estimated 30 cities across the whole country.

These recent incidents of nationwide labour activism all began with common issues affecting workers in different parts of the country, such as arbitrary company policy changes in the case of Lalamove or structural problems in construction industry which forced crane operators to take action. These triggers quickly created cohesion and solidarity among the workers who all understood they were fighting for a common cause.

Given the huge distances separating the workers, they turned to online social media tools to organise their collective action. They established closed QQ and WeChat groups with clear rules and, in the case of the crane operators, even identity screening to verify that each group member was in fact a colleague and not a saboteur.

The high level of organization was also reflected in the coherent and reasoned set of demands the workers presented in each case: crane operators proposed carefully designed pay scales with salary increases according to job type and seniority, while van drivers were conscious of the competitive nature of their business and only took action when pay cuts threatened to make them actually lose money. The workers evidently conducted a thorough debate and a certain level of consensus was reached before their collective demands were presented to their employers.

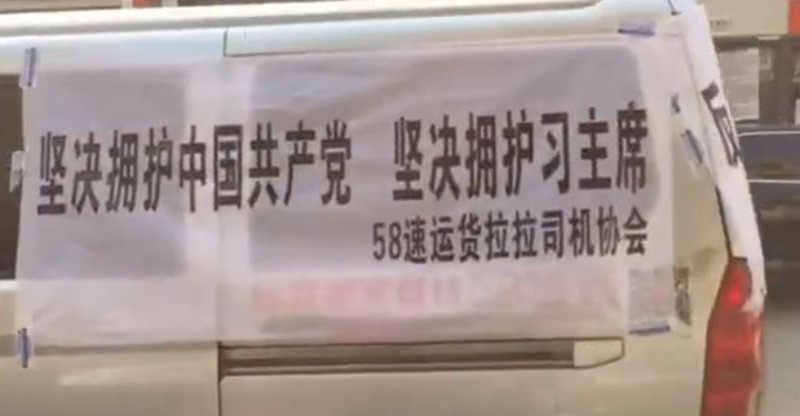

The workers also displayed a keen understanding of the social and political environment in staging protests that would prove effective but not provoke a violent or repressive response from the local authorities. The crane operators, for example, called on colleagues across China to “take a break and go see your extended families on Labour Day,” but urged group members not to hold high-profile protests. In one case, the workers even moved a protest from a train station to a public park to avoid disrupting traffic. Lalamove drivers staged slow drive protests in half a dozen cities, many decorating their vans with slogans supporting the Communist Party and General Secretary Xi Jinping.

Lalamove van drivers resolutely support Xi Jinping.

The above examples demonstrate very clearly that China’s workers have the desire, ability and wherewithal to organize within one diverse corporation or even a whole sector and present a clear set of demands. What they don’t have is a trade union that can represent them in negotiations to resolve their disputes.

The official All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) is under intense pressure to do a better job in representing workers and it has taken some steps towards that end. In April it announced a membership recruitment drive in the rapidly growing logistics and services sectors, while last year Shanghai’s local union created a food delivery workers’ union. All too often however union officials lack the ability or understanding to act in a positive manner. And sometimes they make matters worse, as was the case in a recent strike at an electronics company in Zhuhai, where officials claimed their main responsibility was to maintain social stability rather than negotiate a settlement with management.

The tower crane operators’ strikes in particular posed an important challenge to the credibility of the official union. As labour relations expert Wang Jiangsong, noted:

This is the first instance of such a large-scale, nationwide, collective action by industrial workers in China for more than a decade… This may in fact be the first instance of its kind ever.

Wang pointed out that the crane operators’ strike differed from past cross-country industrial actions like the strikes and online organizing carried out by Walmart workers in 2016 as it was not limited to one particular company. In the absence of proper union representation, crane operators effectively created their own “federation” online and translated their actions offline, he said.

Crane operators stage protest in Tianshui, Gansu

The ACFTU would be wise to pay close attention to this new wave of cross-country collective actions or better yet, invite elected representatives from the crane operators or van drivers into the union and learn from their rich experience in representing workers.

It is undeniable that the ACFTU has a lot to learn when it comes to genuinely representing workers, and the lessons of organizing at the grassroots, building solidarity and successfully engaging in collective bargaining are readily available if it chooses to look.