Cost reduction mindset in industry leads to poor labour conditions and inadequate care for patients.

This article is a summary of a CLB report originally published in Chinese.

China continues to enforce stringent lockdowns in response to outbreaks of Covid-19. In this pandemic year so far, CLB’s Strike Map has recorded 12 incidents of medical workers protesting. When workers at a hospital in Liaoning province protested in July after not receiving wages for several months, they were told that Covid-19 had affected the hospital’s income.

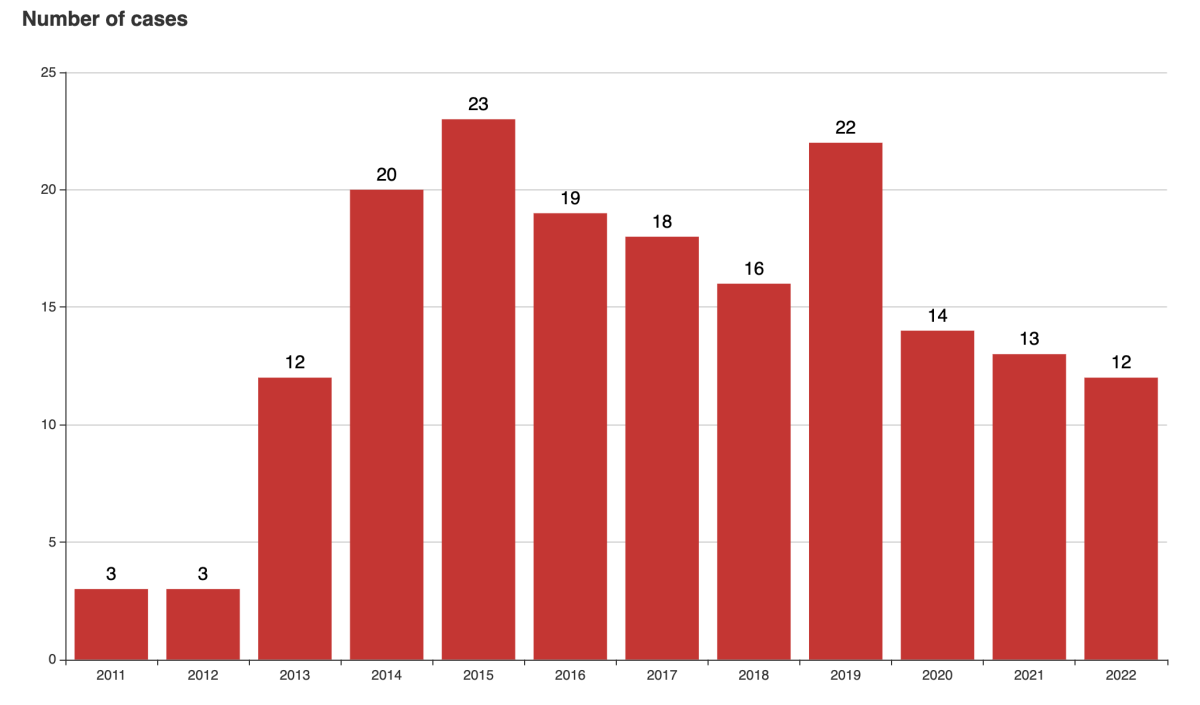

However, such problems are not new and cannot be blamed on the pandemic alone. Over the last ten years, CLB has recorded strikes erupting at similar rates and higher. In 2019, the Strike Map recorded 22 cases of medical workers turning to collective action.

CLB Strike Map Incidents in Medical Industry, 2011 - 2022

These actions are expressions of long-standing grievances. While unpaid wages were the root cause of half the strikes so far this year, workers also requested pay increases, social insurance, and other demands. Interestingly, the proportion of the demands other than wage payment is higher than in other industries, where 70-95 percent of incidents can be over wages, such as in the construction sector.

Prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, Xiao Li, a nurse in the intensive care unit of a Shenzhen hospital, worked three to four 12-hour shifts per week. He told CLB he would only find out his work schedule a week in advance, and he also had to make time for training and study arrangements.

Xiao said that nurses in Shenzhen were paid 6,000 to 8,000 yuan a month in 2018, close to the average salary in the region. In more remote cities, where up to ten nurses can compete for a single job, wages can be as low as 1,000 yuan a month. In those cities, nurses rely on working overtime to boost their income.

As the Covid-19 outbreak continues, medical staff have expressed concerns about the rapid increase in workload, overwork and lack of protective equipment. According to National Health Commission requirements, there should be 0.4 nurses to every bed. A nurse told the media that her department was short nine nurses this year.

Short on nurses but unwilling to hire

Even before the pandemic, the South China Morning Post reported in 2019 that 2,300 tertiary hospitals in China were technically operating with a full staff, but they were still unable to cope with demand for medical care.

Though hospitals could use more nurses, they still lower nurse salaries and cut staff numbers, creating a vicious cycle of overtime, which prompts some nurses to leave. Hospitals are reluctant to hire more.

The reluctance to hire is the result of a lack of public funding and the fee charging mechanism. Most large, general hospitals in China are public, but the government has been decreasing support over the years. Public hospitals, therefore, have become more reliant on less secure sources of revenue, such as insurance payments and out-of-pocket payments.

From 2009 to 2019, only 7-10 percent of the annual revenue of public hospitals came from the government, according to the China Health Statistical Yearbook.

Meanwhile, the government has retained control over the price setting of medical services in public hospitals. As far back as 2016, the People’s Daily reported that public hospitals have not adjusted their rates for a long time, only charging about ten percent of real costs for nursing. This practice has contributed to a long running stereotype that doctors are earners while nurses only increase operating costs.

Private care workers fill the gap

In the 1990s, families of patients began resorting to hiring medical care workers at their own expense to take care of their family members. These types of care workers have since become a formidable workforce, but the level of their professional training is not standard.

Many care workers lack professional knowledge as basic as how to turn over patients after surgery, according to interviews with frontline nurses in a January 2022 Legal Daily report. Though care workers come into contact with bodily fluids and are at high risk, many of them lack understanding of transmission of diseases.

According to a field survey conducted by Fujian provincial authorities in 2020, over 90 percent of care workers were educated at junior high school level or below. Some experts suggested that care work by those without official qualifications should be banned to protect the interests of patients; others proposed a system of grading nurses or assigning work to professionally-trained assistant nurses. Some also suggested training the existing care workers to make them qualified and prevent unemployment.

Care workers have relatively low demands for labour rights. Some of them accept that receiving their pay on time is enough, and they consider social security and other benefits as optional for their employment.

In Shanghai, almost three-quarters of care workers work more than 70 hours a week, and their workplace insurance is not guaranteed, according to a Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference document published this year.

In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in 2021, almost one-quarter of the care workers hired by hospitals and those dispatched by labour dispatch companies did not sign labour contracts, according to a survey conducted by the provincial trade union. The survey also shows that almost two-thirds of care workers in the region have an average monthly salary of less than 4,000 yuan.

Clear solutions to systemic industry problems should be taken up by trade union

This relatively large workforce of nurses and care workers lacks labour protections and is paid low wages, all while having to work intensely. Hospitals prefer to let patients and families hire care workers to reduce costs, while overworking trained nurses and refusing to hire more. The cost reduction mindset affects both types of workers, and the problem of understaffing lingers.

This situation shows little sign of abating as young people are increasingly reluctant to enter the nursing profession. Income instability is their most pressing problem, but workplace conditions are closely linked to the vicious cycle within hospitals.

Until basic workers’ rights are enforced and nurses and care workers are given adequate pay and professional training in line with the work they are hired to do, hospitals will continue to be understaffed and nurses overworked. Unions have a role to play in negotiating with hospitals on behalf of nurses and care workers to improve working conditions and the quality of care for patients.

Further CLB reading: