By Jennifer Cheung

Just about every time a regional government in China increased its statutory minimum wage this year it seemed to make headline news. However, even after hikes of up to 30 percent in some provinces, the minimum wage across China remains barely enough for a subsistence existence.

All workers earning the minimum wage still have to do overtime, sometimes excessive overtime, in order to make a decent living. A hospital porter in Guangzhou for example, told CLB that he earned around 4,000 yuan in November but almost two thirds of that came from overtime pay. His basic salary was only 1,339 yuan, close to the local minimum wage of 1,300 yuan, and in order to get 4,000 yuan per month he’d had to do an estimated 172 hours of overtime.

The highest minimum wage in China (1,500 yuan per month) is in the booming southern metropolis of Shenzhen. But even here, employers are struggling to attract workers because, as one netizen points out, to pay for three meals a day, transportation, rent, mobile phone usage and daily utilities in Shenzhen, you would need about 1,600 yuan each month.

Shenzhen plans to increase the minimum wage even further to 2,650 yuan a month by 2015, according to Zhang Siping, a member of the city’s Party Standing Committee, who pointed out that within the next three years, the majority of Shenzhen enterprises would be high tech companies who could easily afford the proposed minimum wage level. However, 2,650 yuan a month is hardly a decent wage in Shenzhen now, and because of inflation, it will most likely be little more than a substance wage in 2015.

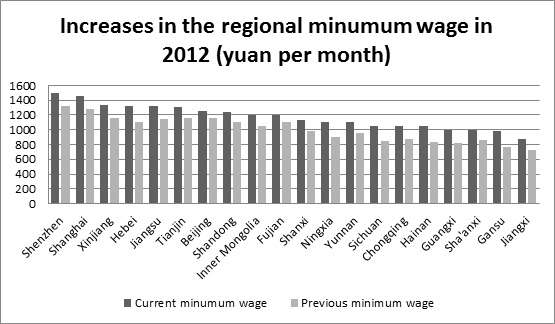

Apart from Shenzhen, the highest minimum wage levels in China are still in the traditional manufacturing centres of the southeastern coastal provinces, plus the remoter regions of Xinjiang, Tibet and Inner Mongolia, which are keen to attract labour from central and eastern China.

Some of the biggest increases in the minimum wage in 2012 were in China’s inland provinces, which have seen greater economic growth and employment expansion over the last few years. The largest increase this year was in Gansu, which raised its minimum wage by nearly 30 percent to 980 yuan this April, followed by Hainan by 26 percent, and Sichuan by 24 percent. See chart.

Note the figures in this chart are for the highest minimum wage in each region. The lowest rate could be as little as two thirds of the highest rate.

However, there is still a noticeable gap in minimum wage levels between many inland provinces and Guangdong, the province with the highest number of migrant workers. As such Guangdong could just about afford to abandon its promised increase in the minimum wage this year from the current level of 1,300 yuan per month to around 1,470 yuan, after receiving vociferous objections from the business sector.

Unlike Shenzhen, Guangdong still has large numbers of labour intensive, low cost manufacturers that can put pressure on the government to maintain minimum wage levels at the current level. A worker at a labour rights organization in Guangdong estimates that 80 percent of the factories in his district pay the statutory minimum as a basic wage. However, as the cost of living continues to rise in Guangdong, especially with the increase in food prices, pressure to raise the minimum wage will eventually outweigh the pressure exerted by the business community.

And if the Guangdong government delays the increase for too long, it seems certain that workers will simply take matters into their own hands and stage strikes and protests demanding better pay and working conditions regardless.