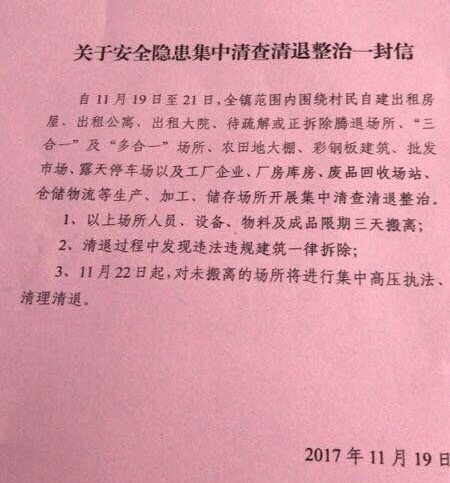

Only one day after the deadly fire which claimed 19 lives in Xinjian village, in the southern outskirts of Beijing, a pink piece of paper was circulating in the neighbourhood. It was an eviction ultimatum, no government agency bothered to sign it. The anonymous eviction order, dated 19 November 2017, warned that tenants, landlords, factories, markets, warehouses, recycling yards, parking lots and farmers across Xihongmen township, which contains Xinjian village, would face “intensified efforts for the detection and removal of safety hazards;”

- All personnel, infrastructure, raw materials and merchandise need to be removed within three days.

- All illegal or unauthorised structures discovered will be demolished.

- From 22 November, all who do not leave will be faced with targeted mid- to high-intensity police force.

Since the warning letter was not signed by any government agency, it is impossible to verify the actual extent the eviction order and how many of Xihongmen’s 175,000 residents have been forced to evacuate. However eyewitnesses report and online video shows hundreds of people, possibly thousands, on the move. Other reports claim similar eviction notices are being enforced in other Beijing districts such as Fengtai, Changping and Haidian, affecting maybe 100,000 people.

Eyewitnesses in Xihongmen said that on Wednesday 22 November people were desperately scrambling to gather their belongings and move on. Photographs show entire families walking away with their bags, empty shops and factory floors, and security personnel and demolition equipment on standby.

It remains a mystery where these migrants mostly from rural China will move to once they leave the Beijing suburb.

One resident said, “Small factories in the area have moved several times before. Workers usually follow these factories, but this time it’s a big clean-up, they will probably have no choice but to go back to their hometowns.”

The official media in China has so far towed the government line in reporting the fire and underplayed the subsequent evictions. However, several online commentators have spoken up for the migrant workers in the area.

One reader commented: “Nobody cared about their safety before, now they chase them away. Whose fault is it? Tenants should not be taking the fall!"

And in a vaguely titled blogpost to avoid censorship, sociologist Sun Liping pointed out that a tragic fire should not be used as an excuse for evicting entire towns in the name of safety.

Sun argued that “China is going through a process of rapid urbanisation, there is a large influx of rural migrants into cities” due to “developmental imbalances” and “concentration of resources within a few cities” it is only natural that people from rural areas chose to move to small towns, and people from small towns move to bigger cities. “This is a natural step in the industrialisation and economic development of a country.”

Sun highlighted the counterintuitive nature of pushing rural migrants out of “first tier” cities like Beijing and Shanghai. “What happens when second tier cities also decide to get rid of them? Where can they go? Is this a solution?”

A now deleted article (archived by China Digital Times) by “Plan C” voices support for rural migrants who are often referred to as the “low end workforce,” reminding urban middle classes that these are the same people who deliver their online purchases at incredibly fast speeds, offer chauffeur services for inebriated party goers in the middle of the night, basically people who work hard to earn a living, just like anybody else, but come from rural areas and probably can only afford to live in shoddy shanty towns.

“They have no voice in the public debate, they were not given a chance to claim their right to a fair chance to live in this city,” Plan C said.

Hu Xijin, the outspoken editor of the Global Times, also got involved asking in a Weibo post “how will the evacuated population support themselves?” But he also acknowledged “broader popular opinion in Beijing” by asserting that “people are concerned about economic recession, about lives becoming less convenient” once migrants are gone.

Echoing Sun Liping’s argument, Plan C asserts that “they are not low end labour force, they are an essential link in the urban ecosystem. They are human beings”