At the height of Hong Kong’s fifth wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, the management office of residential housing unit Riviera Gardens in Tsuen Wan issued a notice stating that a group of 12 care workers from mainland China was isolated in a 50 square metre unit. This followed on questionable reports that non-local care workers who were recruited under special pandemic-related measures were paid double that of local hires.

In this investigation, based on CLB’s two original reports written in Chinese (see Part I and Part II), we explore the working conditions for workers in residential care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong, the experiences of local workers versus non-local workers, and potential solutions to the ongoing public health and labour challenge of staff shortage under the backdrop of the pandemic.

Photograph: HUI YT / Shutterstock.com

In February 2022, the fifth wave of the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in Hong Kong, leading to over 9,000 deaths. The elderly were hit the hardest. On 10 March, a total of 722 residential care homes for the elderly (about 90 percent of all residential care homes) had reported Covid-19 cases. About 22,000 seniors and 6,000 employees were infected in the fifth wave. By early June, the government had conducted mass testing at over 800 residential care homes and did not find lingering community transmission.

The staffing levels of elder care homes in Hong Kong have been low for decades. But the staffing situation became critical this year, with some employees contracting the virus and others taking unpaid leave to avoid infecting their family members. At the end of February, the Hong Kong government announced that for three months it would relax the rules for importing elder care workers, allowing residential care homes to rely on temporary labour, mostly from mainland China. (Hong Kong’s foreign domestic worker population of “helpers,” largely from the Philippines and Indonesia, are not eligible to take up these jobs in residential care homes.)

Although bringing in non-local workers can be part of the solution, low staffing levels are largely the result of poor working conditions: long working hours and low wages of workers in residential care homes for the elderly. Improving labour conditions and fostering more dignity for both patients and workers is a more sustainable way to alleviate the labour shortage and is in the interest of local and non-local workers alike.

Our research involved an interview with the Community Care and Nursing Home Workers General Union secretary general - prior to the union’s recent disbandment - and review of relevant policy documents, reports, and articles. We have found that the residential care home for the elderly industry has one of the lowest salaries and one of the largest number of mainland temporary workers among all industries in Hong Kong. Non-local temporary workers are vulnerable to a greater degree of labour exploitation, and importing labour may contribute to worsening working conditions in Hong Kong. In fact, protecting the rights and interests of local and non-local workers are not in conflict with each other. But protecting these interests will be more difficult with the disappearance of several unions that have acted as a trusted resource for workers.

(All dollar amounts in this article refer to Hong Kong dollars.)

Labour Conditions for Elder Care Workers in Hong Kong

Residential care facilities for elders in Hong Kong are categorised either as “care and attention homes for the elderly” or “nursing homes.” Both provide accommodation and daily care, but the latter provides a higher level of care for those whose health is deteriorating. According to the law, the minimum requirement for the ratio of nursing staff to residents at nursing homes is 1:5, whereas that of care and attention homes ranges anywhere from 1:20 to 1:60.

In addition to categorising facilities according to the type of care provided, another distinction is whether the facility is government-subsidised or private. Workers at non-profit government-subsidised care homes generally have better pay and working conditions than at for-profit private facilities. But in 2000, Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department introduced a lump sum grant subvention system that has acted as a strong pressure to keep salaries low. Under the lump sum grant subvention system, government grants on salaries are based on the median scale salary times the number of workers, leading institutions to cap a worker’s salary at the median scale.

The starting salary of personal care workers in government-subsidised institutions is $15,560, and the maximum salary is $22,725. The median monthly salary in private institutions is $14,150.

However, not all care workers are employed as personal care workers who are guaranteed a minimum labour standard. For example, in 2018, a government-subsidised residential care home of the Lutheran church had hired workers as “support attendants” who were paid about $3,000 less per month than personal care workers.

In government-subsidised institutions, the daily working hours is eight. In private institutions, workers often work 11-12 hours per day. During the fifth wave of the pandemic, according to Inmedia.hk, some health workers in private institutions reported working up to 14 hours per day for 13 consecutive days without time off. Each staff member was assigned to care for 50 patients at a time due to staff shortage.

One worker is quoted as saying, "Every night, I would have nightmares. I was working every single day, and there wasn’t a night that I could sleep peacefully.” In addition, the worker described seeing their familiar patients “one by one diagnosed [with Covid-19], in so much pain, and it was just me alone to take care of them, which was so difficult.”

Experiences of Non-local Workers in Hong Kong Elder Care Homes

Poor working conditions in Hong Kong residential care homes have led to a shortage of staff and a demand for non-local workers, mostly from mainland China. According to 2021 government statistics, around 26,000 people work in residential care homes for the elderly, and the industry is short of 2,500 workers. The statistics are similar to pre-pandemic labour conditions. As of May 2018, the industry employed 2,648 non-local workers.

Non-local workers are vulnerable to more severe labour exploitation than local workers. Although the Supplementary Labour Scheme that governs imported labour stipulates that non-local workers are “accorded no less favourable treatment as that enjoyed by local workers under the labour laws.” In addition, employers must pay non-local workers no less than the industry median salary and additional hours are required to be compensated. However, past violations in the elder care industry have been recorded.

Equal pay for equal work?

Some media outlets reported that the monthly salary for mainland temporary workers could exceed $30,000, and claimed that the amount is more than double the median salary ($14,150) of local staff. However, CLB has found that the direct comparison of these two salaries is inaccurate.

The government's sixth round of the anti-epidemic fund provides a monthly subsidy of $2,000 to employees of residential care facilities, on top of their base salary which must be at least the median salary in the industry. If the facility includes patients who are quarantined or infected with Covid-19, employees will receive a daily subsidy of $500. It is likely that the calculation for non-local workers was arrived at through the following: $14,150 median monthly salary + $2,000 subsidy + ($500 x 30 working days in the month) = $31,150

This calculation does not account for workers taking rest days, that the anti-epidemic sixth round of funding only lasts for five months, and workers do not necessarily receive the additional subsidy of $500 every day. Further, it is unclear whether there is a minimum number of working days necessary to qualify for the subsidies, or whether the $500 subsidy should be used for hotel quarantine.

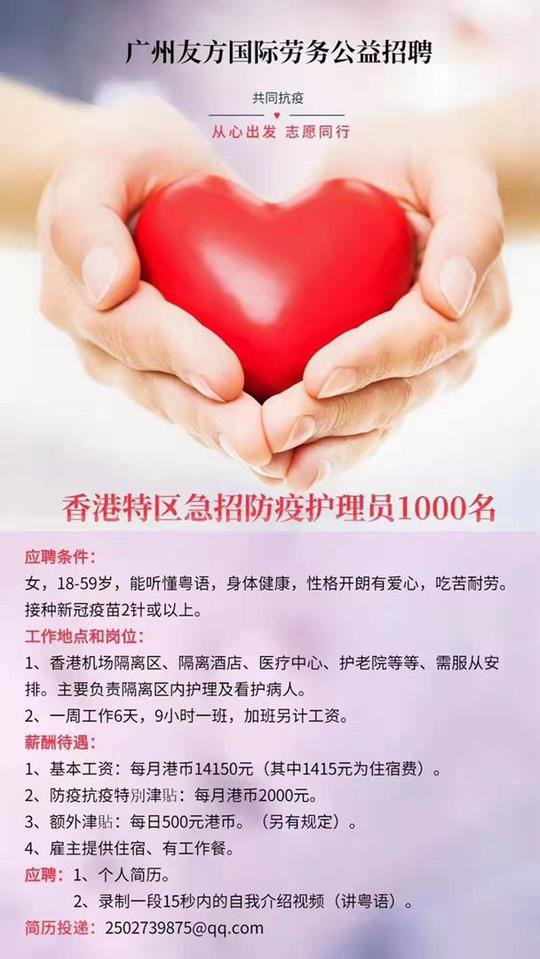

Recruitment advertisement, image provided by the Community Care and Nursing Home Workers General Union. The advertisement is targeted at care workers in Guangzhou, stating that Hong Kong is seeking 1,000 workers for pandemic prevention needs. It specifies that women ages 18-59 are preferred and that worksites include quarantine and isolation facilities as well as residential care homes for the elderly. Working conditions are 6 days per week, 9 hours per day, and overtime is compensated. The salary is $14,150 per month, and the pandemic subsidies are listed.

The reality is that the anti-epidemic subsidies are available to both local and non-local workers alike, and the lack of effort to publicise the subsidies available to all workers contributed to the labour shortage during a time of need. After local workers understood that they were eligible for the subsidies, more workers applied for these jobs.

More vulnerable to labour exploitation

In 2018, nine non-local workers of Wing Kwong Care Home for the Elderly quit their jobs and protested for several days in front of the government headquarters. According to their contract, their monthly salary was $12,000 and they were to work nine hours daily, in compliance with the Supplementary Labour Scheme. However, the workers’ actual monthly salary was $8,000 and their daily working hours were 12, with the hours over nine going uncompensated. They also paid $21,000 in agency fees. They worked seven days a week and were not permitted public holidays. Some suffered injuries while on the job, which were not compensated, either.

Salaries in Hong Kong are higher than in mainland China. Mainland temporary workers at Wing Kwong Care Home said they had been tolerant, hoping to save as much money as possible to send back to their hometowns to support their families and enable their children to study. Workers said that they had "no complaints" about their work conditions. If their bosses had not intimidated them to prevent them from collecting unpaid wages when the contract was over - they even got scolded for turning on the air conditioner and drinking water while on the clock - they said they would not have protested and just accepted it.

From such accounts, it is probable that reported cases of mistreatment of non-local workers are only the tip of the iceberg. Some non-local workers have sought help from local unions and the Labour Department, according to Cheng Ching-fat of the Community Care and Nursing Home Workers General Union. But, he said, it is difficult for non-local workers to win their cases in the Labour Tribunal because workers may lack evidence such as time records, pay records, and other materials.

The judicial process can take anywhere from a few months to half a year, and the cost of living in Hong Kong is so high that many non-local workers are not willing to wait for resolution of their cases. Where this legal approach is less effective, unions have used public pressure on employers to help non-local workers receive their compensation.

The Labour Department conducts regular inspections of elder care facilities, but according to an interview with the Federation of Trade Union staff in 2020, these are not always effective. Non-local workers are afraid of retaliation for making honest reports to the Labour Department, particularly when their employers are present for the interviews, and the penalties on facilities are not adequate to prevent harm.

Under the pandemic, the working conditions for non-local workers have worsened. The Supplementary Labour Scheme stipulates that employers must provide accommodation for non-local workers and can deduct up to 10% of their wages as rent. In the past two years of the pandemic, many residential care homes have a low occupancy rate and their income has dropped, leading to employers housing non-local workers in vacant rooms at the job site.

This practice is also encouraged by the government as a closed-loop system to avoid spreading the virus to the public. However, many institutions lack isolation space, and the housing situation may be inappropriate, leading to the cramped and unsanitary conditions for mainland carers housed at Riviera Gardens in Tsuen Wan this year.

Context of Staff Shortage in the Elder Care Industry

Society generally views the job of elder care as low-skilled and undesirable labour, which is an important factor that prevents more people from entering the industry. When Hong Kong enacted a minimum wage in 2011, gaps among wages for various low-skilled jobs tended to close, popularising jobs with higher pay and lower intensity than that of a residential care home worker, such as security guard.

The work of a carer itself is stigmatised and viewed as a “dirty job,” a description that is repeated in media and interviews on the topic. These attitudes actively harm the elderly population, because the stigma affects the labour conditions of carers and, consequently, the quality of care that is administered. Reports of seniors being restrained or having bedsores and other problems are common. Family members complain that care workers scold the elderly and do not give them adequate privacy when tending to their personal care needs. These are the consequences of the shortage of manpower and the high pressure of the work.

Photograph: hanohiki / Shutterstock.com

Improving the professionalism of elder care work and increasing career development opportunities can help to improve the situation, and some foreign experiences can be used for reference. For example, according to Cheng Ching-fat, in Japan, elder care is a professionalised job with a clear promotion ladder. Professionalisation and a good working environment also enable caregivers to better understand the needs of the elderly, thereby improving relationships with patients and their families.

In 2015, the Hong Kong government launched a program to encourage young people to join this career path, but recent data and interviews with those who joined the program show that low pay and better career prospects elsewhere have not attracted young people to elder care work. Only 30 percent of those who joined the program were still employed in the industry as of 2021.

The incidence of elders suffering from chronic diseases and disabilities is increasing. In the future, the demand for residential care homes will only rise, and the problem of insufficient staffing will become more serious. In 2017, Law Chi-kwong, Secretary for Labour and Welfare, stated that in the ten years from 2037 to 2047, a total of 458 subsidised residential care homes for the elderly would need to be built to meet demand. At the current rate of building two to three facilities each year, the demand will not be met.

Conclusion

Elder care facilities in Hong Kong are facing social stigma, increased demand, shortage of workers, low salaries and limited upward career mobility, and consistent quality of care problems. Government-subsidised institutions are under pressure to accumulate reserves and reduce expenses, which exacerbates each of the identified problems.

Private institutions mainly serve low-income seniors and are extremely dependent on government funding, making it difficult to significantly improve staff treatment and service quality. An investment of public resources is badly needed to change the situation.

At present, the government and the business community mainly promote the importation of non-local workers to solve the problem, leaving low-wage and undesirable labour to others. Although the labour shortage suggests that Hong Kong residential care homes for the elderly may need to import non-local labour to a certain extent, this will never resolve the deeply-rooted problems in the industry.

In addition, Cheng Ching-fat of the Community Care and Nursing Home Workers General Union urges for increased public participation in relevant policy making. He noted that the Elderly Commission, which advises the government on these issues, comprises owners and managers of care homes, but workers and service users should have a larger voice.

For more in-depth information about this topic, please see our original Chinese-language reports: 【香港安老院工人(上)】“高薪”照顾员承受厌恶-工会为中港工人争权 and 【香港安老院工人(下)】待遇低下与人手不足的恶性循环,安老院为何没能打破?