Job creation and higher living standards have long been key objectives for the Chinese government. However, the vast majority of China’s citizens still have a disposable income of less than 5,000 yuan per month, and over two-thirds of the population make substantially less. Millions of workers in traditional industries have been laid off and many of the new jobs being created in the service sector are insecure and poorly paid.

The legal framework established in the late 2000s to protect workers and ensure fair labour standards has largely failed to do so – as employers have found ways around the rules – even to the extent that millions of workers cannot be sure they will be paid on time.

The minimum wage, which varies by region, has risen gradually over the last decade. Still, nowhere has it kept pace with the cost of living, especially in major cities. The gap between the rich and poor continues to widen and, despite long-standing government policies to reduce rural poverty, the urban and rural divide remains stubbornly in place.

For the Chinese version of this article please see 就业和工资 on our Chinese website.

Outline (jump to sections):

- Legal provisions on employment and the payment of wages

- The erosion of legal protection

- Job creation and labour market imbalances

- Managing unemployment

- Wage arrears

- Minimum wage levels

- Income inequality

- Analysis and conclusion

Legal provisions on employment and the payment of wages

China has a comprehensive legal framework that defines the rights and obligations of employers and employees, primarily the 1995 Labour Law and the 2008 Labour Contract Law (amended 2013), which contain clear provisions on employment contracts, working hours and payment of wages, benefits and the termination of employment, specifically:

- Employers are required to conclude a written employment contract with employees (Labour Contract Law Article 10).

- The employment contract shall specify the term of the contract, the job description and place of work, working hours, rest and leave, labour remuneration, work safety protection etc. (Labour Contract Law Article 17).

- The standard workweek in China is 40 hours (eight hours per day, five days per week) although flexible working hours are allowed under certain conditions (State Council 1995 Provisions on Working Hours of Staff and Workers).

- Overtime shall be paid for any work exceeding standard working hours and overtime shall not exceed three hours a day or 36 hours per month (Labour Law Article 41).

- Overtime pay should not be less than 150 percent of an employee’s wages during normal work days; 200 percent on rest days, and 300 percent on national holidays, such as the Lunar New Year (Labour Law Article 44).

- Wages shall be paid in legal tender to the workers in person on a monthly basis. No deduction of wages for personal gain may be made from wages due to workers. The payment of wages may not be delayed without reason (Labour Law Article 50).

- An employer shall pay wages to workers during their statutory holidays, marriage or funeral leave (Labour Law Article 51).

- If their contract is terminated, employees are entitled to severance pay based on the number of years employed at a rate of one month’s wage for each full year worked (Labour Contract Law Article 47).

The erosion of legal protection

These provisions give workers a broad range of rights and a reasonable level of legal protection. However, ever since the Labour Contract Law went into effect on 1 January 2008, employers have sought to undermine it and local government officials have failed to implement it effectively, leaving it up to employees themselves to defend their rights either through the arbitration and court systems, or by collective action.

By far the most common employer response to the implementation of the Labour Contract Law was to reassign existing employees and hire new employees as “agency workers” (劳务派遣), rather than as formal employees who require contracts. This was seen as a way to reduce the benefits companies had to pay and make hiring and firing easier. Abuse of the system was so rampant that in 2013, the government sought to tighten loopholes in the law and ensure that only a limited number of “temporary, auxiliary or substitute” staff could be employed as agency labour. Nevertheless, many employers continued to employ staff as agency workers, denying them the same pay and conditions as regular employees. By the end of 2016, more than a thousand agency workers at FAW-Volkswagen, a Sino-German car manufacturing joint-venture in the north-eastern city of Changchun, had had enough and filed a complaint with the trade union demanding equal pay for equal work. After a long campaign, some of the workers won a partial victory, but others were reclassified as outside contractors, with even less protection than agency workers.

FAW-Volkswagen agency workers stage a protest at the plant in Changchun in May 2017

Other employers have sought to reduce costs by introducing flexible work-hours schemes that erode the protection provided by the standard workweek. In May 2016, American retail giant Walmart imposed a so called “comprehensive working hours system” on its roughly 100,000 employees in China. The move (almost certainly illegal under existing provisions) allowed the company to schedule working hours according to its own needs, reduce overtime and other benefits, as well as prevent already low-paid employees from holding down a second job. Walmart workers responded with strikes, legal action and widespread online resistance. See CLB’s 2017 research report on the Walmart workers' struggle for more details.

Other companies, especially in the manufacturing sector, sought to overcome legal restrictions on labour contracts by hiring student interns from vocational schools to meet demand during peak production periods. One of the most notorious employers of student labour is electronics manufacturer Foxconn, which recruited 3,000 interns from the Zhengzhou Urban Rail Transit School in September 2017 in order to catch up with orders after a shortage of workers caused delays in production of Apple’s iPhone X. As extensively documented in the book Dying for an iPhone (2020) by Jenny Chan, Mark Selden and Pun Ngai, government-set quotas and kickbacks for teachers make these “internships” little more than coerced labour at less than minimum wage, without labour contracts and accompanying legal protections, and without employers paying into social security and other government benefits programs. This factory work has nothing to do with their elected courses, no additional learning opportunities are provided, and students are told they will not be allowed to graduate unless they participate in the “program.”

Many workers in the new service industries, in particular e-commerce and the sharing economy, do not have proper employment contracts. They are instead hired as individual contractors, with little or no job security and none of the welfare and social security benefits those with formal employment contracts are entitled to. The number of such gig economy workers with formal contracts is rapidly dwindling, as those who previously had contracts are forced to accept new arrangements, and workers who enter the sector subsequent to this phenomenon have no option to sign a labour contract. The multi-billion dollar food delivery business, for example, is increasingly adopting an informal relationship with individual contractors who bid for delivery orders via smartphone apps without signing any formal contract with the company.

Similarly, the basic terms and conditions of employment for many workers in these new service industries can be changed at short notice. This includes payment rates, and the intense competition for customers has led to numerous business failures with workers being laid off without any compensation. Even in more traditional sectors, employers may require workers to be transferred across the country with little notice or compensation, often at a lower wage. If workers object to the new conditions, they may lose their jobs. And after such transfers, workers may face bureaucratic issues related to wages and benefits as their contract is under the authority of the previous jurisdiction.

Job creation and labour market imbalances

China’s working age population (16 to 59 years) has been shrinking since 2012, with the country’s overall labour force reaching a peak of 807 million in 2016. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s total labour force at the end of 2018 had declined by just over a million to stand at 805.7 million. The total number of employed persons has remained steady at around 776 million for the last three years, although there was a slight decline from 2017 to 2018, according to official statistics.

The Chinese government continues to stress its commitment to job creation, seeing it as an essential component in the maintenance of social and economic stability. Until the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the economy in 2020, China had created about 13 million new jobs in urban areas each year on average over the previous five years and kept unemployment largely under control at around five percent (see below for more details).

The problem, however, has not been the lack of new jobs but that many of the new jobs are poorly paid, insecure and require employees to work long hours in often dangerous conditions. The vast army of an estimated two million couriers delivering packages from online shopping networks are an obvious example of the new employment opportunities and problems in China. One courier described how they “work 12 hours each day, delivering more than 300 items per day.”

We sort several tons of packages, even the lightest loads are around seven or eight kilograms. Every day I cover more than 40 kilometres and climb over 46 flights of stairs, and all the time my phone must be on 24 hours a day. I need to pay for all my calls myself. My average monthly wage is around 3,400 yuan.

In addition, China’s labour market has long struggled to provide employers with the well-trained and competent workers they need to make their businesses grow. The mismatch between the needs of job seekers and employers has been highlighted on numerous occasions over the last few years, especially whenever new college graduates enter the job market. About 8.7 million graduates entered the job market in 2020, most of whom will have little chance of finding a suitable job. China’s academic, examination-orientated college system routinely fails to prepare students for the demands of the employment market. Vocational schools have likewise long been criticized for not producing the skilled or semi-skilled workers businesses need. However, attempts by the government to make the system more effective by promoting privatization and encouraging greater corporate involvement have yet to yield any positive results.

Another major problem is the fact that many businesses are reluctant to invest any time or resources in training; rather, they expect new staff to have all the skills they need to perform their jobs straight away. The view of many business owners is that providing training to their own staff will only encourage them to look for a better paying job elsewhere. This short-sighted view will have to change if China is to bridge the skills gap that is stalling the transition from a low-wage to a skills-based economy.

Some manufacturers and logistics businesses are looking to resolve their staff recruitment and training problems by turning to automation. However, despite the boom in robotics manufacturing, finding positions that robots instead of people can do has proved more difficult than expected. Even Foxconn, the best-known proponent of robotic labour, has scaled back its automation plans. The company’s enigmatic boss, Terry Gou, wanted to have one million robots in place by 2013, but in 2015, the general manager of Foxconn’s automation technology development committee, Day Chia-Peng, revealed that the company had only about 50,000 fully operational industrial robots installed in its Chinese factories by the target date. He said the company planned to add at least another 10,000 robots each year for the next five years to its facilities in China, replacing staff in the so-called “3D” jobs – positions that are dirty, dangerous and dull. The target for 2020 is 30 percent automation in Foxconn’s mainland factories. However, even that figure now seems optimistic and Foxconn is focusing instead on expanding production in markets with cheaper labour outside of China such as India.

Throughout much of the 2010s, China’s official unemployment rate hovered steadily around four percent and the number of unemployed persons remained stable at around nine million. This rigidity stemmed from the very narrow base the statistics were drawn from. Only workers with an urban household registration (about half the total workforce) were included in the data, and the unemployment rate only referred to the proportion of officially registered urban job-seekers to the total number of employed urban workers. It ignored all rural workers and rural migrant workers, foreign workers, as well as those in insecure, part-time or casual work.

These statistics were widely acknowledged as being next to useless in gauging the true state of unemployment in China, so in 2018 the National Bureau of Statistics introduced a new system based on monthly surveys of workers in urban areas, reportedly based on International Labour Organization (ILO) standards. The first survey results put the overall urban unemployment rates for January, February and March 2018 at 5.0, 5.0 and 5.1 percent respectively. The rate in the 31 major cities surveyed was slightly lower; 4.9, 4.8 and 4.9 percent in the first three months. By way of comparison, China’s overall rate was lower than both the average unemployment rate in developing countries (5.5 percent) and developed countries (6.6 percent).

While the new survey method is certainly an improvement on the previous official unemployment rate, it still does not represent the whole picture. Rural unemployment is not included and importantly neither are people in short-term or precarious employment who make up an increasingly large proportion of the urban working population. Some estimates put the number of people in “flexible employment” at more than 200 million. The official figures came under further scrutiny during the 2020 coronavirus outbreak when amid anecdotal reports of mass unemployment, the rate only went up to a high of 6.2 percent in February 2020. The relatively low figures underlined the extent to which traditional methods of calculating unemployment can no longer fully represent the reality of employment in the new economy.

As Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China with the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group, pointed out in the South China Morning Post in August 2020:

“The problem is that the unemployment rate itself cannot reflect overall employment pressure. If you work part-time, you may not be part of this rate. But the wage pressure is still high because you are underemployed.”

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the Chinese government introduced a range of relief measures to private companies in order to prevent mass layoffs. However, these measures only really benefited larger or medium-sized enterprises. Many small and micro enterprises, with little capital or access to credit, had no choice but to lay off staff or close down completely. The government extended unemployment benefits to some workers, such as rural migrants, who would not necessarily qualify. However, because the benefits are so low – lower than the minimum wage – many workers never bothered to apply, preferring to seek whatever employment they could find in order to make a living.

Workers are routinely owed several months or even half a year’s wages in arrears when they are laid off. The non-payment of wages is by far the most important single cause of labour disputes in China today, not just for laid-off workers but employees in many sectors of the economy where the payment of monthly wages is not guaranteed. About 83 percent of all the collective protests recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in the 18 months from January 2019 to June 2020 were related at least in part to wage arrears. In the construction industry, where the non-payment of wages is endemic, around 99 percent of all disputes are caused by wage arrears.

Chinese government officials are well aware of this chronic issue, admitting that the “deep rooted conflict” in the construction sector remains unresolved and acknowledging, moreover, that the problem is spreading to other industries. In a People’s Daily report in January 2017, a Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) official noted that:

"On the one hand, the legacy issues plaguing the construction and manufacturing sectors haven’t been rooted out and disputes over wage arrears keep occurring at high intensities. On the other hand, new economic sectors like e-commerce are following the same path."

The official blamed market uncertainties, rapid expansion and consolidation, and the growth of precarious work for aggravating the situation in the new economy.

The MOHRSS proposed several measures to address the problem and issued a 2020 deadline to “basically eradicate wage arrears.” However, most proposals were simply administrative or judicial measures designed to mitigate the failings of employers rather than tackle the fundamental imbalance in labour relations that allows employers to not sign formal employment contracts and delay payment of wages whenever they see fit. By mid-2020, it was obvious from the data on CLB’s Strike Map that not only had wage arrears not been eradicated, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the problem was only getting worse.

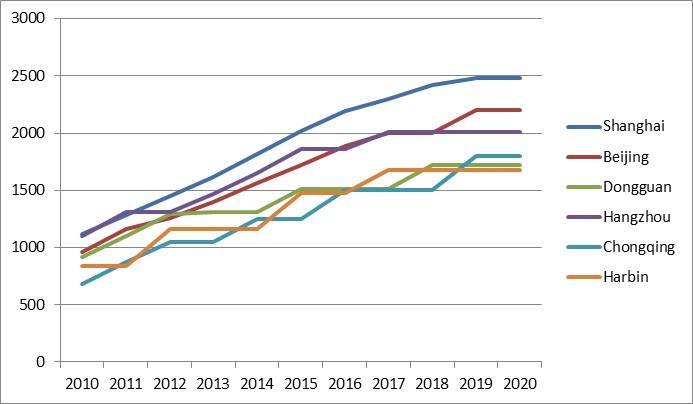

Minimum wage rates in China are determined by regional governments, based on local living costs, local wages and the overall supply and demand for labour. As a result, there is considerable variation in minimum wage levels across major cities, let alone poorer rural areas. The highest monthly minimum wage as of July 2020 was in Shanghai (2,480 yuan), which was roughly double the minimum wage in smaller cities in provinces such as Hunan, Hubei, Liaoning and Heilongjiang. In setting this wage, local governments are focused on industry concerns and local investment rather than on ensuring a liveable wage for workers, and employers likewise still find ways to avoid paying the minimum wage.

China’s Minimum Wage Regulations (最低工资条例), implemented by the then-Ministry of Labour and Social Security in March 2004, stipulate that regional governments should adjust the minimum wage in a timely manner and at least once every two years. In the mid-2010s, however, the economic powerhouse of Guangdong, in a bid to slow the outflow of manufacturing businesses to other countries and the Chinese interior, decided to switch to triennial adjustments. Other provinces and regions soon followed suit and the frequency of increases declined noticeably towards the end of the decade. And in 2020, minimum wage increases across China were basically put on hold in response to the economic fallout from the Sino-U.S. trade war and the Covid-19 pandemic. (see graph below).

Monthly minimum wage rates in selected cities 2010-2020

Guangdong’s policy of only increasing the minimum wage once every three years has severely impacted the lives of low-paid workers there, according to a 2017 survey conducted the Hong Kong-based group Worker Empowerment. The majority of workers surveyed earned not much more than the minimum wage and, as a result, struggled to maintain even a basic existence. They were forced to live in low-rent, poor quality housing, spend most of their income on food, and many walked to and from work to avoid transport costs. In a subsequent report, Worker Empowerment estimated that a more realistic minimum wage - equal to 40 percent of the average wage in 2019 - would be 3,728 yuan per month in Guangzhou; 2,331 yuan in Dongguan; 2,588 yuan in Huizhou; and a minimum of 2,298 yuan in fourth-tier cities like Heyuan, compared with the current levels of 2,100 yuan, 1,720 yuan, 1,550 yuan and 1,410 yuan, respectively.

The Worker Empowerment recommended wage was in line with the government’s Minimum Wage Regulations, which state that each region should set its minimum wage at between 40 and 60 percent of the local average wage. However, very few cities have ever reached that target. Moreover, the discrepancy between the average and the minimum wage has actually increased over the last decade as higher wages for privileged few has pushed the average wage up and wages for the lowest-paid have stagnated. In many cities such as Guangzhou and Chongqing, the minimum wage is now less than 24 percent of the average wage, while in Beijing, which has some of the highest-paid employees in the country, it is just under 20 percent.

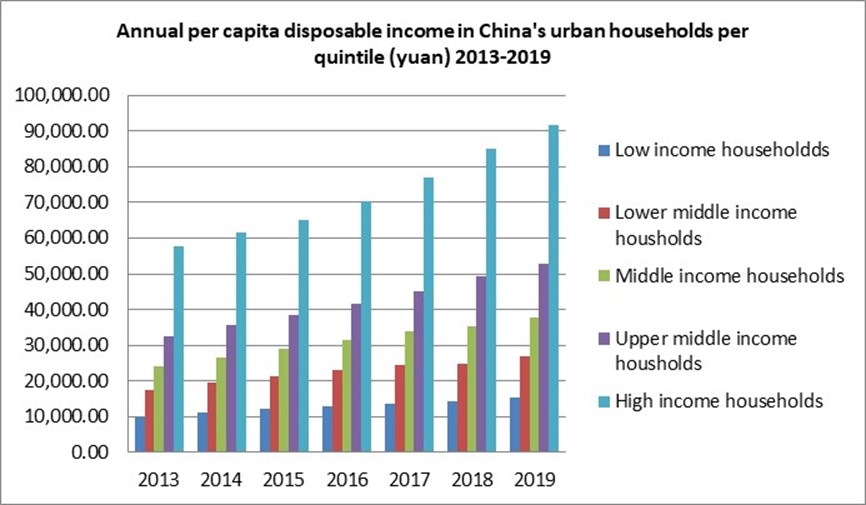

In June 2020, China’s Premier Li Keqiang surprised many observers when he announced during a press conference at the end of the annual National People’s Congress that there were still 600 million people in China with monthly disposable income of little more than 1,000 yuan. The statement was all the more notable given the huge resources the government had devoted to poverty alleviation over the previous five years. However, the premier’s statement was based on publicly accessible official statistics. And further analysis reveals the extent to which only a very small percentage of the Chinese population have benefited from the economic reforms, while the majority have seen incomes rise only marginally.

An analysis of the data for 2019 by a team from Beijing Normal University showed that in 2019, 43 percent of the population (600 million) had an income of less than 1,090 yuan per month, 69 percent had an income under 2,000 yuan, 84 percent less than 3,000 yuan per month and 95 percent earned less than 5,000 yuan. Only the top 0.6 percent earned more than 10,000 yuan a month. China had close to 400 billionaires in 2019, according to Forbes, with tech entrepreneur Jack Ma heading the list with a net worth of U.S. $38.2 billion.

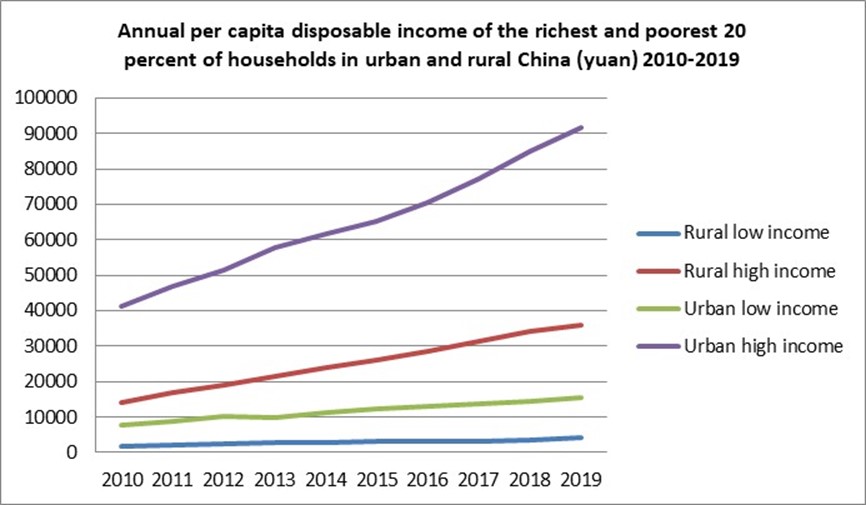

Moreover, the data shows that income inequality in China’s cities has been getting steadily worse over the last decade. The annual average per capita disposable income of the richest 20 percent in China’s cities increased by nearly 34,000 yuan in the seven years from 2013 to 2019, while the disposable income of the poorest 20 percent in urban areas grew by just over 5,500 yuan during the same period (see chart below).

Rural residents make up 75.6 percent of those earning less than 1,090 yuan per month, according to the Beijing Normal University report. When rural residents are taken into account, the wealth gap becomes even more stark. The gap between the annual per capita disposable income of the richest 20 percent in urban areas (91,683 yuan) and the per capita disposable income of the poorest 20 percent in rural areas (4,263 yuan) in 2019 was 87,420 yuan, more than double the 39,288-yuan gap between the two sample groups in 2010. (see chart below).

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2015, 2020.

The urban-rural divide is probably the most important factor in wealth inequality in China today. Not only do rural families have lower incomes, they also generally have more elderly relatives and children to support – a legacy of the discontinued family planning policies and the heavy urban bias in the pension system. (See our explainer on social security for more details.) Moreover, nearly all of China’s best healthcare, education, cultural and social services are located in urban areas. Whereas urban residents have reasonably unfettered access to such services, rural residents often have to pay excessive fees on top of the cost of travelling to and staying in the city that provides the services. Although smaller and, to some extent, medium-sized cities have begun to relax their administrative barriers to rural migration, there are no signs that major cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou will make it easier for rural migrants to gain access to their jealously guarded social welfare, healthcare and education systems.

Looking at longer term trends, Thomas Piketty, Li Yang and Gabriel Zucman found that the gap between urban to rural average incomes had risen from less than 200 percent in 1978 to about 350 percent in 2015. In China as a whole, the top ten percent earners’ share of national income rose from 27 percent in 1978 to 41 percent in 2015, while the share of the bottom 50 percent dropped from 27 percent to just 15 percent. Piketty, et al., also found that while the average annual income growth in China was 6.2 percent from 1978 to 2015, income growth for the bottom 50 percent of the population was just 4.5 percent per year and income growth for the top one percent was nearly nine percent. The super wealthy, those in the top 0.001 percent of the population, saw incomes grow the fastest of all, increasing by 10.4 percent per annum on average.

A superficial glance at China’s major cities seems to show a reasonably affluent society: young, hard-working, middle-class families, determined to make a better life for themselves. This illusion was shattered however in late 2017 when the municipal government of Beijing embarked on a 40-day high-profile campaign to clean out the city’s shanty towns and evict the so-called “low-end population” who produce, market, and deliver the goods, services and lifestyle products that Beijing’s middle class families aspire to have. The evictions revealed the harsh truth that the affluence of China’s cities depends almost entirely on the impoverishment of the underclass.

The Chinese government has made the alleviation of poverty, fairer income distribution and the expansion of the middle class a high priority. In 2017, General Secretary Xi Jinping stated in his address the 19th Party Congress in Beijing that:

We will expand the size of the middle-income group, increase income for people on low incomes, adjust excessive incomes, and prohibit illicit income. We will work to see that individual incomes grow in step with economic development, and pay rises in tandem with increases in labour productivity. We will expand the channels for people to make work-based earnings and property income. We will see that government plays its role in adjusting wealth redistribution, and moves faster to narrow the income gap and ensure equitable access to basic public services.

The speech, however, lacked any concrete proposals on how these gaols could be achieved, particularly in an economy that is now largely free from overt government controls.

One of the key reasons why low-wage earners have so far not been able to earn a decent income and bridge the gap to the middle class is because they lack the institutional means to bargain collectively for better pay and working conditions. Workers have demonstrated time and again over the last decade that they have the means and the ability to organize collectively, stage strikes and protests in response to specific labour rights violations. What they do not have, however, is a trade union that can represent them in collective bargaining with employers.

China’s sole legally-mandated trade union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) has a titular presence in many workplaces, but the union representatives are largely under the sway of management and have no real connection to ordinary workers. There is an increasingly urgent need for China’s workers to assert more control over the union and make it more representative and effective. The Chinese government, too, will need to put pressure on the ACFTU to play its part in improving labour relations and maintaining long-term social, economic and political stability.

A version of this article was first published in 2008. It was last updated in September 2020